Iraq is stepping up repatriation of its citizens from a camp in northeastern Syria housing tens of thousands of people, mostly wives and children of ISIS militants but also supporters of the militant group.

It’s a move that Baghdad hopes will reduce cross-border militant threats and eventually lead to shutting down the facility.

After US-backed and Kurdish-led fighters defeated ISIS in Syria in March 2019 — ending its self-proclaimed “caliphate” that had ruled over a large swath of territory straddling Iraq and Syria — thousands of ISIS fighters and their families were taken to the camp known as al-Hol.

Many of them were Iraqi nationals.

Today, Iraqi officials see the facility, close to the Iraq-Syria border, as a major threat to their country's security, a hotbed of the militants' radical ideology and a place where thousands of children have been growing up into future militants.

It's "a time bomb that can explode at any moment,” warned Ali Jahangir, a spokesman for Iraq’s Ministry of Migration and Displaced. Since January, more than 5,000 Iraqis have been repatriated, from al-Hol, with more expected in the coming weeks, he said.

It is mainly women and children who are sent home. Iraqi men who have committed crimes as ISIS members rarely ask to go back for fear of being put on trial. Those who express readiness to return, have camp authorities send their names to Baghdad, where the government does a security cross-check and grants final approval, The Associated Press reported.

Once in Iraq, the detainees are usually taken to the Jadaa camp near the northern city of Mosul, where they undergo rehabilitation programs with the help of UN agencies before they are allowed back to their hometowns or villages.

The programs involve therapy sessions with psychologists and educational classes meant to help them shed a mindset adopted under ISIS.

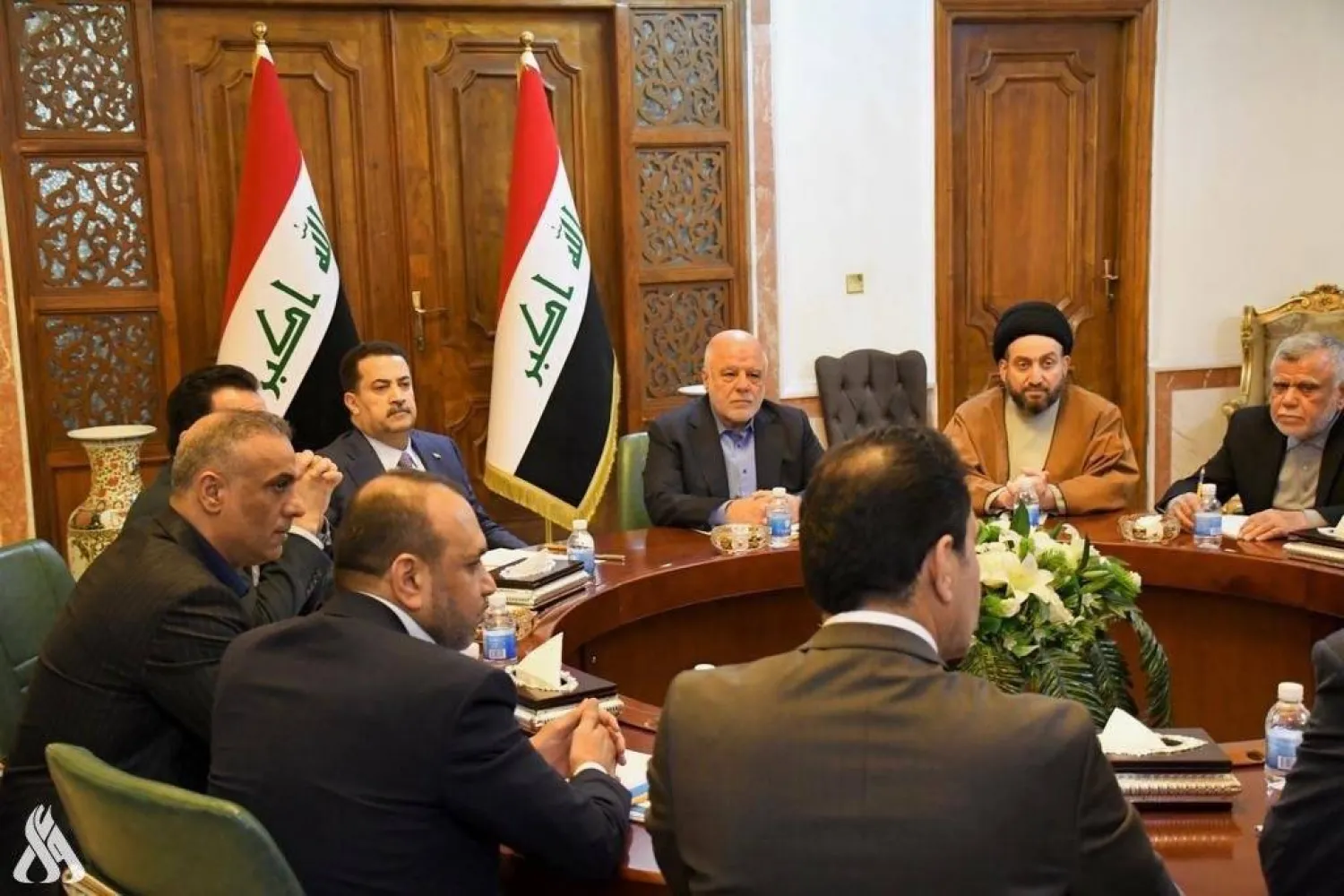

Iraq has been urging other countries to repatriate their citizens from al-Hol, describing the camp at a conference held in June in Baghdad as a “source for terrorism.”

At the gathering, Iraq’s Foreign Ministry spokesman Ahmad Sahhaf said it was critical for all countries with citizens at al-Hol “to repatriate them as soon as possible in order to eventually close the camp.”

The alternative, he warned, is a resurgence of ISIS.

The heavily-guarded facility, overseen by Syrian Kurdish-led forces allied with the United States, was once home to 73,000 people, the vast majority of them Syrians and Iraqis. Over the past few years, the population dropped to just over 48,000 and about 3,000 were released since May.

Those still at the camp include citizens of about 60 other countries who had joined ISIS, which is why closing al-Hol will require efforts beyond Iraq and Syria, an Iraqi Defense ministry official said, speaking on condition of anonymity in line with regulations.

The camp currently has 23,353 Iraqis, 17,456 Syrians and 7,438 other nationalities, according to Sheikhmous Ahmad, a Kurdish official overseeing camps for displaced in northeastern Syria. And though the foreigners are a minority, they are seen by many as the most problematic at al-Hol — persistently loyal to the core ISIS ideology.

So far this year, Ahmad said, two groups of Syrians have left the camp for their hometowns in Syria. Earlier in September, 92 families consisting of 355 people returned to the northern city of Raqqa, once the capital of the ISIS “caliphate.” In May, 219 people returned to the northern town of Manbij.

Syrian nationals are released when Kurdish authorities overseeing the camp determine they are no longer a threat to society. The release of other nationalities is more complicated, since their countries of origin must agree to take them back.

Those of non-Syrian or Iraqi nationalities live in a part of the camp known as the Annex, considered the home of the most die-hard ISIS supporters. Many of them had travelled thousands of miles to join the extremist group after ISIS swept across the region in 2014.

In late August, 31 women and 64 children from the camp were returned to Kyrgyzstan on a special flight, the Kyrgyz Ministry of Foreign Affairs announced and thanked the US government for providing “assistance and logistical support” for the repatriation.

But other countries — particularly in the West — have largely balked at taking back their nationals who were part of ISIS.