Saudi Arabia’s connection with Hajj is a long-standing tradition marked by significant achievements. This journey began with the first pilgrimage under the reign of the Kingdom’s founder, King Abdulaziz, soon after he entered Makkah in December 1924.

While Hajj is a great honor for Saudi Arabia, it also comes with immense responsibility.

King Abdulaziz Calls on Muslims to Join Hajj

King Abdulaziz has invited Muslims from around the world to join the Hajj pilgrimage. He promised to ensure their comfort, security, and rights.

Due to ongoing unrest in Jeddah at the time, pilgrims were directed to travel to the holy city of Makkah through the ports of Rabigh, Al Lith, and Al Qunfudhah.

In his message, King Abdulaziz said: “We warmly welcome pilgrims from all Muslim nations. We are committed to their comfort and safety, and we will facilitate their journey to Makkah from Rabigh, Al Lith, or Al Qunfudhah. Our forces have secured these areas, and we will take all necessary measures to ensure the pilgrims’ comfort.”

King Abdulaziz Welcomes Charitable Initiatives

King Abdulaziz announced that all previous barriers to charitable and economic projects have been removed. He invited everyone to undertake such efforts, assuring that the gates of Hijaz are open and the local government is ready to provide full support and facilities for these initiatives.

Challenges of Hajj Before Saudi Rule

On February 25, 1925, Sultan Abdulaziz bin Abdul Rahman Al Saud issued a call to Muslims, inviting them to perform Hajj. This was before he was declared King of Hijaz. How did he organize the first Hajj season, and what conditions did pilgrims face? Security was a major concern, along with disease, mistreatment by local authorities, and lack of services.

British documents reveal a lack of clear policies. One document notes the anger of Bengali Muslims due to the poor treatment of their pilgrims in the 1924 Hajj season. Another document states that Indian Muslims found the arrangements in Makkah very poor.

Maj. Gen. Ibrahim Rifaat Pasha, who performed Hajj in 1901 and 1908, documented his experiences.

In 1901, he noted, “The ruler of Makkah imposed a tax for the railway, charging each pilgrim one riyal. Pilgrims who refused to pay were detained in Makkah for seven days after Hajj.”

“Some Moroccan pilgrims complained to the governor about being detained. The governor sent a representative, but the pilgrims were beaten by the ruler’s guards and returned empty-handed. A rightful complaint was met with harsh humiliation,” added Pasha.

Pasha also warned that if this injustice continues, people will avoid Hajj, which would harm the Arab economy and Islam.

“Hajj connects Muslims worldwide. Without it, Muslims would be easy prey for colonizers,” he cautioned.

He described the chaos as pilgrims left Makkah, “Pilgrims were stopped to pay another tax of one riyal per camel. The congestion was severe, with harsh enforcement by guards. People fell, bones broke, and luggage was lost or damaged.”

“The sounds of women wailing, children crying, and men arguing filled the air. There was no police to maintain order. This chaos was due to poor tax collection. The government could have appointed more collectors and scheduled departures by caravan to ensure a calm and safe journey for the pilgrims,” concluded Pasha.

King Abdulaziz Acts to Secure Pilgrims

King Abdulaziz faced various challenges and waited several years before annexing Hijaz. Despite having a clear path forward, he avoided actions that might provoke foreign intervention.

He pursued a patient approach, issuing statements and communications to clarify his position regarding the Hijaz government’s treatment of pilgrims, which justified his eventual annexation decision.

However, he delayed due to recognizing the significant difficulties in Hijaz needing comprehensive solutions.

While annexing Hijaz was pivotal for his unification efforts, King Abdulaziz’s primary aim was to protect the holy sites, ensure safe access, establish peace, and address injustices faced by pilgrims.

His vision prioritized swiftly providing essential services and enforcing justice based on Islamic principles. Despite resource constraints, wartime conditions, the siege of Jeddah, and international criticism, King Abdulaziz felt deeply responsible for fulfilling this mission.

Inaugurating the First Hajj Season under Saudi Rule

King Abdulaziz successfully oversaw the inaugural Hajj season during his reign, a milestone achieved through divine guidance, clear vision, and meticulous planning aimed at ensuring security, justice, and enhanced services.

This responsibility was immense, but King Abdulaziz fully grasped its importance, closely monitored its execution, and personally supervised the details. The successful management of the Hajj pilgrimage in the early years of the Saudi state underscored his effective leadership.

Security

After declaring the restoration of security in the Hijaz shortly after entering Makkah, King Abdulaziz moved quickly to enforce order. He warned of severe punishments for anyone endangering security, especially during the Hajj pilgrimage.

He deployed patrols to hunt down criminals targeting pilgrims, ensuring their swift justice. Tribal leaders were cautioned against disrupting pilgrim caravans and held responsible for crimes in their territories. This firm stance deterred further criminal activity.

Health and Municipal Services

Upon arriving in Makkah, King Abdulaziz swiftly appointed his personal physician, Dr. Mahmoud Hamdi Hamouda, to oversee public health.

He took immediate steps to organize health services and educate the public through articles in the early editions of “Um Al-Qura” newspaper. Addressing prevalent diseases and epidemics became a top priority after ensuring security.

Key initiatives included verifying causes of death and issuing weekly statistical reports.

Before the Hajj season, proactive health measures were implemented to prevent diseases, proposing suitable medical teams with a strong focus on prevention.

Several hospitals and health centers were prepared to operate during Hajj. Food and beverage sales, bakery cleanliness, and health guidelines for barbers were monitored closely, with strict penalties for violations.

The cleansing of holy sites and preparation of sacrificial areas were also part of the comprehensive preparations.

Post-Hajj, a health report confirmed the absence of epidemic diseases and a decrease in mortality rates compared to previous years, accompanied by several recommendations.

Water and Food

King Abdulaziz prioritized the maintenance of Ayn Zubaydah’s water channels, ensuring it remained clear to prevent pilgrim thirst, a lesson learned from past Hajj seasons.

Early in Dhu al-Qi’dah, the operation of a water pump was announced to transport water to Mina, with efforts to fill reservoirs ensuring water availability for pilgrims. The King entrusted his advisor, Hafiz Wahba, to oversee these operations, inspecting pumping machinery and reservoirs in Mina and Arafat and reporting back.

Before the Hajj season, efforts to clean and sterilize water channels, reservoirs, and public basins in Mina were completed.

King Abdulaziz also took proactive measures to secure food supplies from various regions, opening markets and ensuring staples like dates, meat, ghee, honey, wheat, barley, corn, and sesame were available from Najd, Asir, Jazan, and Taif.

He appointed Abdullah Al-Fadl to procure goods early from Aden and India, resulting in several ships arriving before Hajj carrying flour, sugar, barley, and kerosene. Caravans of camels also delivered provisions.

Announcements regarding food availability, price monitoring, and weekly price lists were made, with actions taken against monopolistic traders. Some companies advertised affordable food options, ensuring accessibility for all pilgrims.

For Over a Century: Saudi Success in Hajj Management

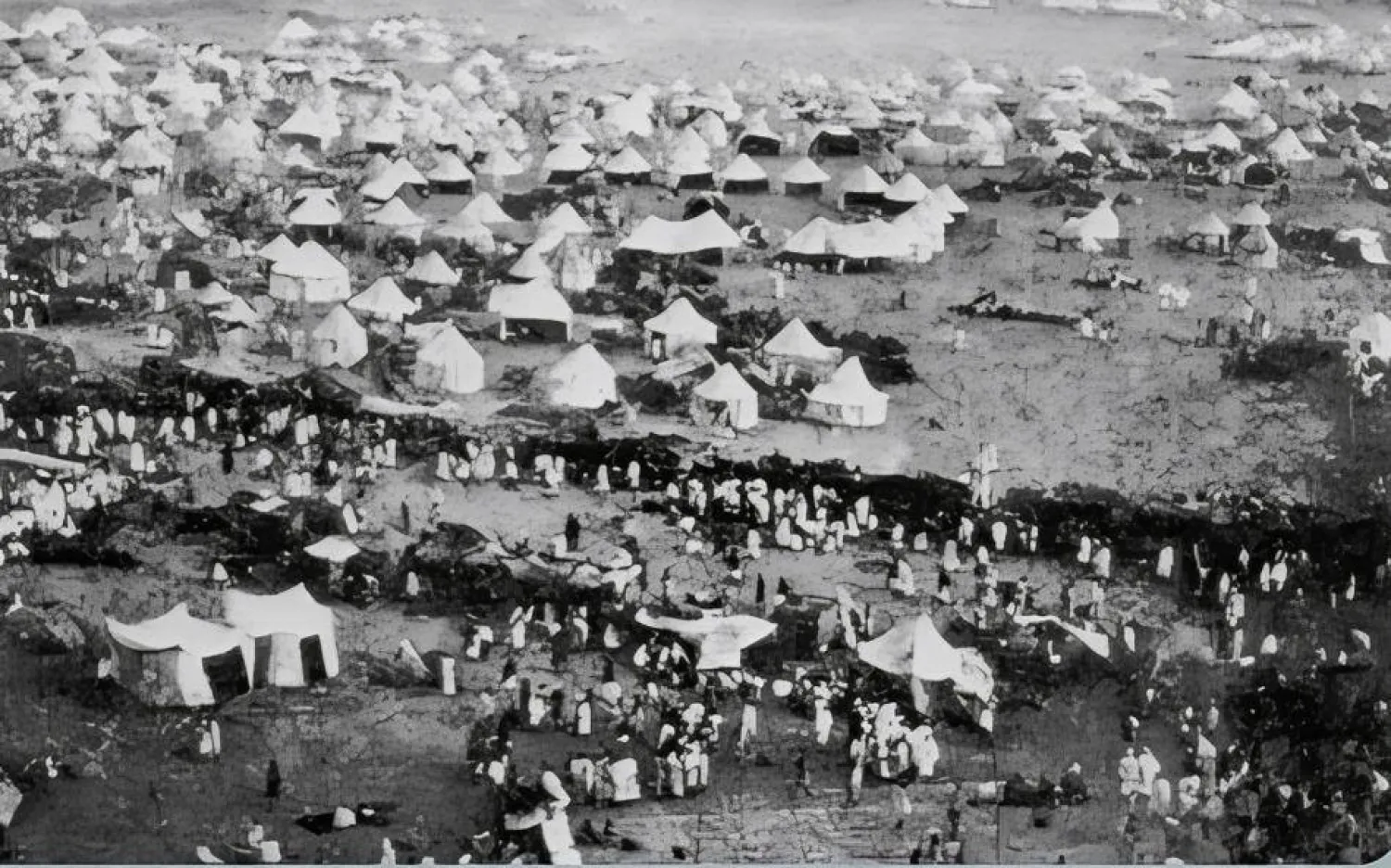

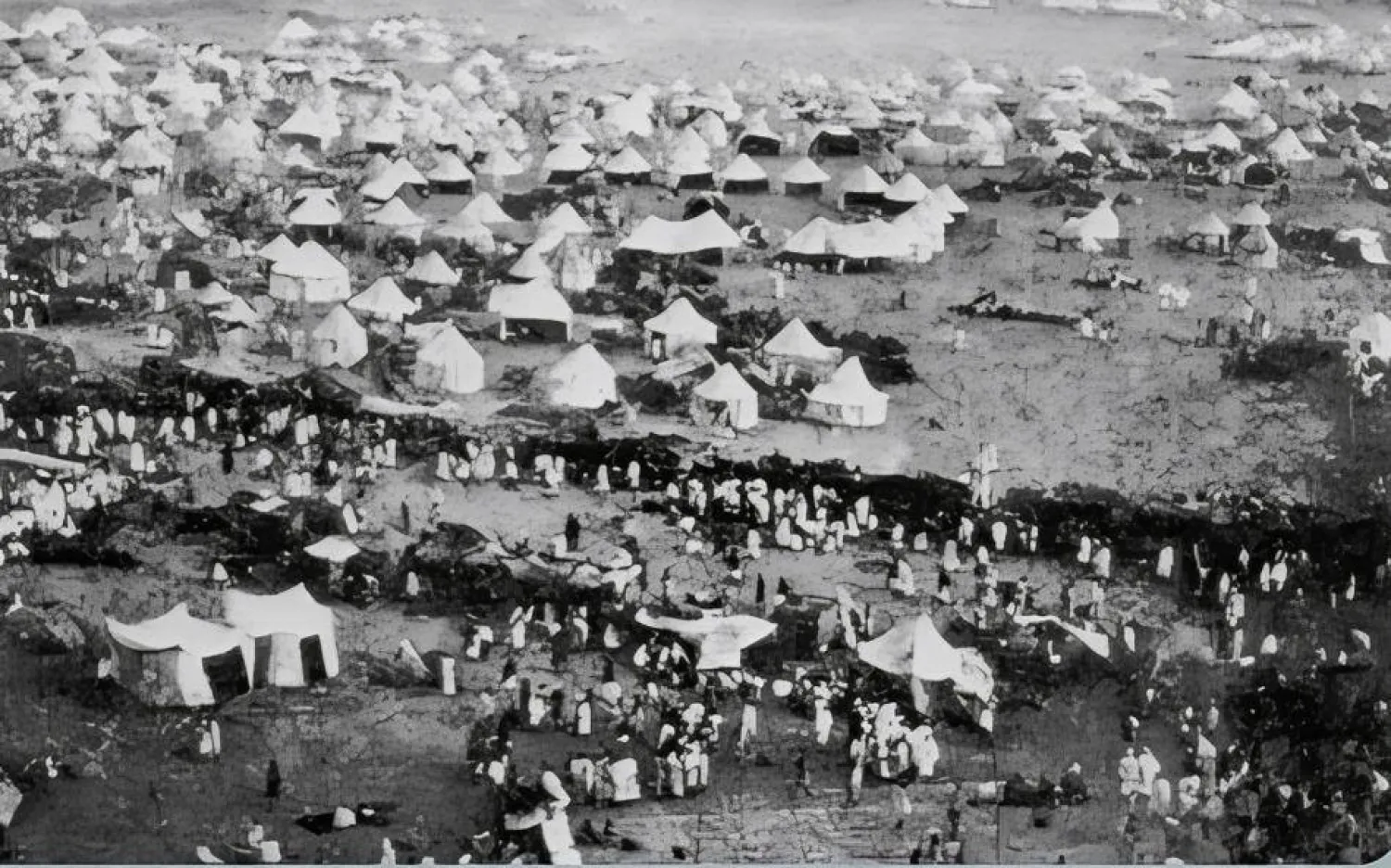

Hajj pilgrims’ camps at the beginning of the Saudi era (Asharq Al-Awsat)

For Over a Century: Saudi Success in Hajj Management

Hajj pilgrims’ camps at the beginning of the Saudi era (Asharq Al-Awsat)

لم تشترك بعد

انشئ حساباً خاصاً بك لتحصل على أخبار مخصصة لك ولتتمتع بخاصية حفظ المقالات وتتلقى نشراتنا البريدية المتنوعة