Cattle farmer Khairallah Yaacoub refused to leave south Lebanon despite a year of Hezbollah-Israel clashes. When full-scale war erupted, he and four others were stranded in their ruined border village.

Yaacoub is among a handful of villagers in the war-battered south who have tried to stay put despite the Israeli onslaught.

He finally fled Hula village only after being wounded by shrapnel and losing half of his 16-strong herd to Israeli strikes.

They had been marooned by constant bombardment and with rubble-strewn access roads all but unpassable.

The two of the five remaining had no mobile phones and could not be located.

"I wanted to stay with the cows, my livelihood. But in the end I had to leave them too because I was injured," Yaacoub, 55, told AFP.

With no immediate access to a hospital, he had to remove the shrapnel himself using a knife to cauterise his wound and then apply herbal medicine to it.

"It was difficult for me to leave my house because warplanes were constantly circling above our heads and bombing around us," he said, describing weeks of sleepless nights amid intense strikes.

Now north of Beirut, Yaacoub said he dreams of returning home.

"When I arrived in Beirut, I wished I'd died in Hula and never left," he said.

"If there's a ceasefire, I will return to Hula that very night. I'm very attached to the village."

- 'Smoke shisha' -

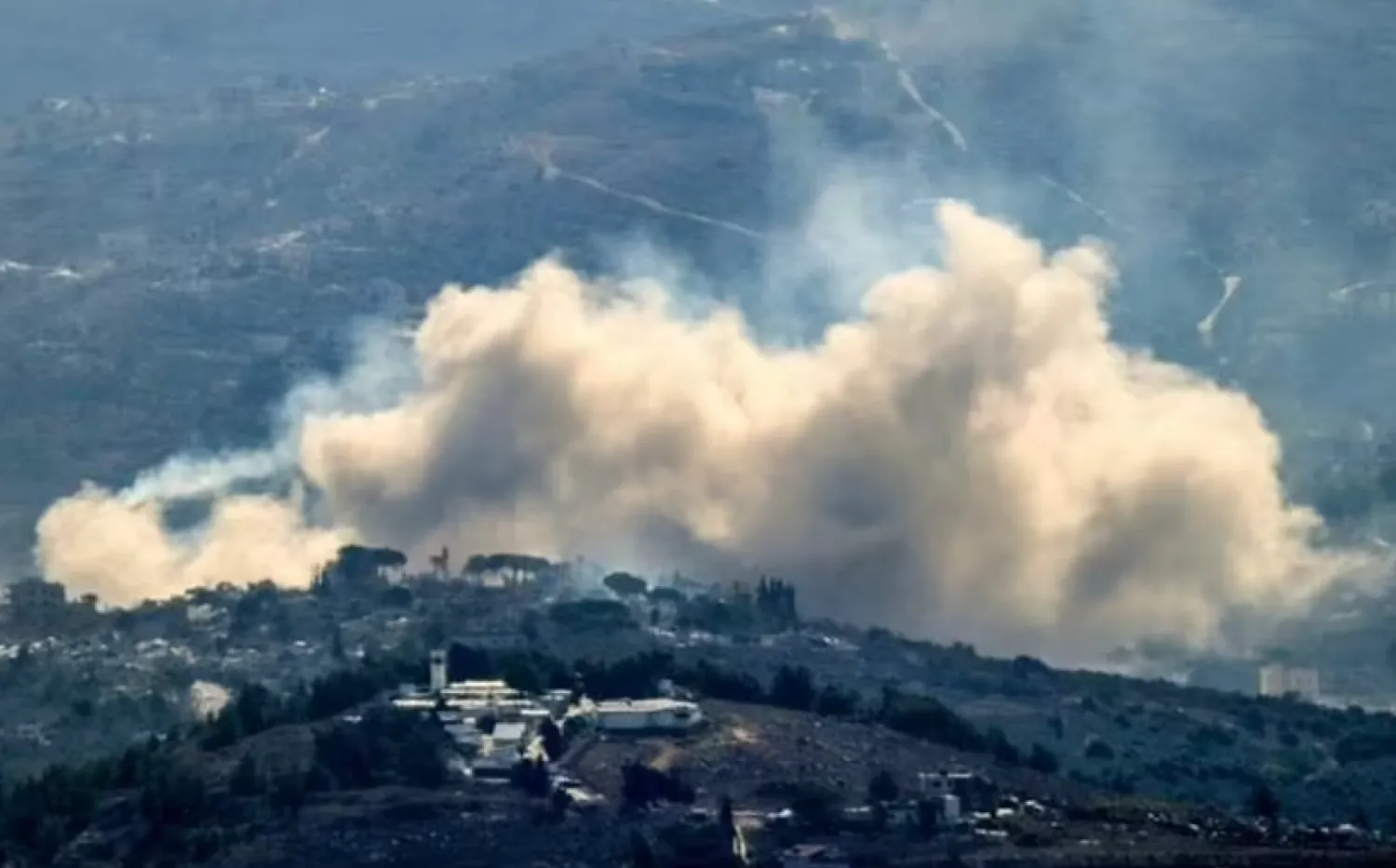

On September 23, Israel began an air campaign mainly targeting Hezbollah strongholds and later launched ground incursions.

According to an AFP tally of health ministry figures, at least 1,829 people have been killed inside Lebanon since then.

The war has displaced at least 1.3 million people, more than 800,000 of them inside the country, the United Nations migration agency says.

Scarred by memories of Israel's occupation of south Lebanon, a few villagers have refused to leave, fearing they might never see their hometowns again.

On October 22, UN peacekeepers evacuated two elderly sisters, the last residents of the border village of Qawzah, to the nearby Christian village of Rmeish.

Christian and Druze-majority areas have remained relatively safe, with Israel mostly targeting Shiite-majority areas where Hezbollah holds sway.

AFP contacted half a dozen mayors, from the coastal town of Naqura near the border to Qana, about 20 kilometres (12 miles) away, who said villages and towns had been emptied.

But just a few kilometres north of Qana, Abu Fadi, 80, said he is refusing to leave Tayr Debba, a village Israel has repeatedly attacked.

"Since 1978, every time there's an invasion I come back to the village," said the retired south Beirut policeman who now runs a coffee stall in the shade of an olive tree.

"I smoke my shisha and stay put. I'm not scared."

- 'No torture' -

About 5,000 people used to live in Tayr Debba near the main southern city of Tyre, but now only a handful remain, he said.

"About 10 houses in our neighbourhood alone were damaged, with most completely levelled," Fadi said.

"I have long been attached to this house and land."

But he "felt relieved" his nine children and 60 grandchildren -- who repeatedly beg him to leave -- were safe.

Bombs are not the only danger southern Lebanese face.

Israeli soldiers detained a man and a nun in two border villages before releasing them, a Lebanese security official told AFP.

Ihab Serhan, in his sixties, lived with his cat and two dogs in Kfar Kila until soldiers stormed the village and took him to Israel for questioning.

"It was a pain, but at least there was no torture," he told AFP.

He was released about 10 days later and questioned again by the Lebanese army before being freed, he said.

A strike destroyed his car, stranding him without power, water or communications as his village became a battlefield.

"I was stubborn. I didn't want to leave my home," Serhan said.

His late father dreamt of growing old in the village, but died before Israel ended its occupation of the south in 2000, and did not return.

Now the family home has been destroyed.

"I don't know what happened to my animals. Not a single house was left standing in Kfar Kila," Serhan said.