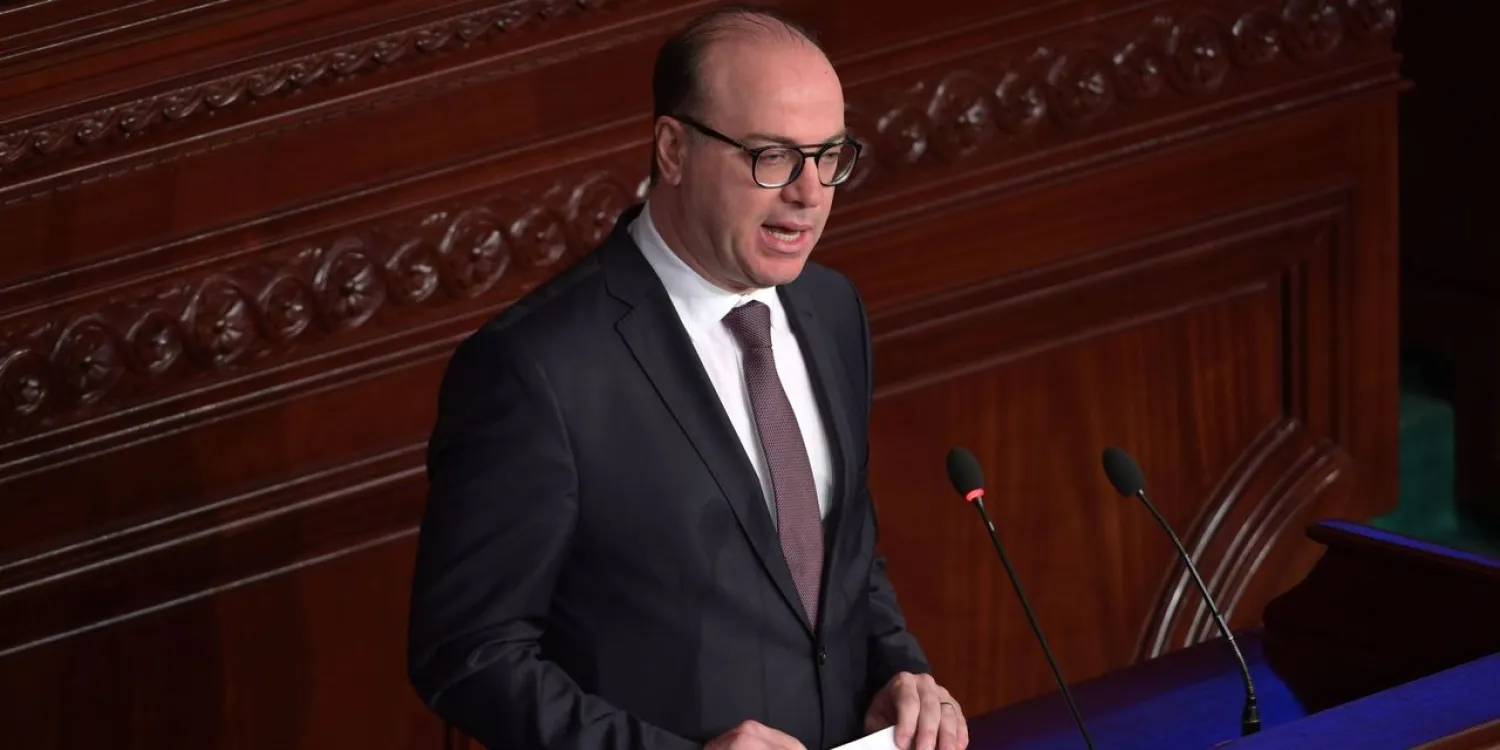

Elias Fakhfakh, a former Tunisian Minister of Tourism and Finance and Social Democratic leader, officially assumed the presidency of the Tunisian government after the October 2019 elections.

Some describe Fakhfakh as the new “golden boy”, and they associate him to his predecessor, Youssef Chahed - who took over the government between August 2016 and February 2020 - to former Prime Minister Mehdi Jumaa (during 2014) and to a group of senior Tunisian officials who entered the political arena after the fall of the rule of Zine El Abidine Ben Ali in the beginning of 2011. Those became known as the “golden boys”.

At the same time, some trade unionists and opposition politicians describe these boys as “France’s men”, indicating that most of them have studied at French universities and assumed responsibilities at the head of French or European economic institutions, and that they had no political role against the rule of Ben Ali before the protests of late 2010 and early 2011.

In any case, Fakhfakh is known for his many friendships in Paris and Western capitals, as his party has been a long-time member of Socialist International, which encompasses 160 political parties, including the French Socialist Party.

Elias Fakhfakh was born in 1972 in Tunis, where he received his early education. He obtained an engineering degree in mechanics and business administration from the Tunisian University in 1995, then moved to France, where he received a master’s degree in mechanical engineering from Lyon’s INSA and a master’s degree in business administration from the University of Évry Val-d'Essonne, on the outskirts of the French capital. He did not return from France until 2006, after obtaining a French passport.

After returning to Tunisia, Fakhfakh supervised branches of French international organizations and was appointed general manager of a French company specialized in the manufacture of auto components. After the merger between the French company and its Spanish counterpart, he was appointed to the new institution.

This career path with European companies enabled Fakhfakh to enjoy French and Western support and made him the new “golden boy”, as happened to his predecessor, Mahdi Jumaa, who was appointed Minister of Industry in 2013 and then head of government in 2014 thanks to his career in French-German companies.

In his speech during the handover ceremony, he said his relationship with his predecessor, Chahed, dated back to his studies and work in France before the spark of the Arab revolutions.

He announced his determination to “lead the country firmly”, underlining his relentless pursuit to be the president of a “strong government that guarantees political stability until the next parliamentary elections” in five years.

He also seemed confident that he would receive the support of the leaders of trade unions, industrialists, merchants, and farmers, as he was a member of the scientific committee of the General Tunisian Labor Union and a businessman at the same time.

Undoubtedly, Fakhfakh’s government is likely to be under scrutiny, awaiting a tangible improvement of the internal socio-political situation and amid the rapid security, political, and economic developments in Libya and Algeria.

Therefore, one of the new prime minister’s top priorities is to employ his strengths and external and local friendships to prevent regional winds from threatening his political future.