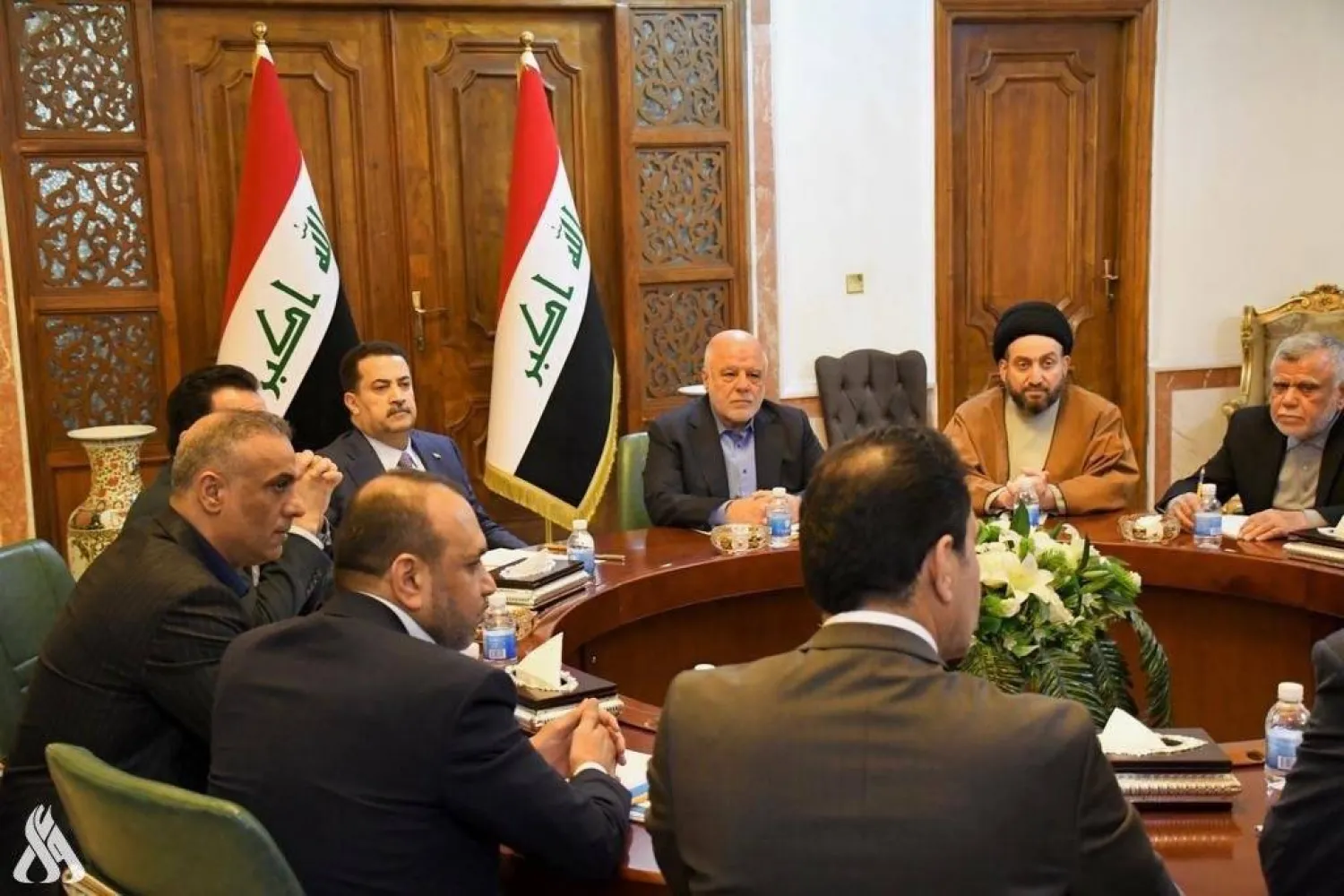

Iraqi Former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki declined at the last minute to attend a meeting of the pro-Iran Coordination Framework on Monday night that was aimed at settling the crisis over his nomination as prime minister.

Instead of declaring that he was pulling out as candidate, as had been expected, Maliki informed his close circle that he is “following through with his nomination to the end,” trusted sources told Asharq Al-Awsat.

Iraq has come under intense pressure from the US to withdraw the nomination. In January, President Donald Trump warned Baghdad against picking Maliki as its PM, saying the United States would no longer help the country.

“Last time Maliki was in power, the Country descended into poverty and total chaos. That should not be allowed to happen again. Because of his insane policies and ideologies, if elected, the United States of America will no longer help Iraq,” Trump wrote on Truth Social.

Maliki also dismissed as “extortion and intimidation” talks of renewed US sanctions on Iraq, added the sources.

However, circles within the Coordination Framework have started to “despair” with the impasse over naming a new prime minister and are weighing the possibility of taking “difficult” choices, they revealed. Maliki has become a prisoner of his own nomination.

The Sunni Progress Party (Takadum) had voiced its reservations over Maliki’s nomination before Trump made his position clear and which has since weighed heavily on Iraq.

‘Indefinitely’

Maliki’s decision to skip the Framework’s meeting on Monday forced the coalition to postpone it “indefinitely”, exposing more differences inside the alliance that have been festering for months. The dispute over the post of prime minister is threatening to evolve into one that threatens the unity of the coalition itself.

Several sources told Asharq Al-Awsat that Maliki had sent the Framework a written message on Monday night informing them that he will not attend the meeting because “he was aware that discussions will seek to pressure him to withdraw his candidacy.”

Maliki was the one to call for the meeting to convene in the first place, they revealed.

Reports have been rife in Iraq that Shiite, Sunni and Kurdish political leaderships have all received warnings that the US would take measure against Iraq if Maliki continued to insist on his nomination.

Former Foreign Minister Hoshyar Zebari told Dijlah TV that “Shiite parties” had received two new American messages reiterating the rejection of Maliki’s nomination.

Necessary choice

Maliki and the Framework are now at an impasse, with the latter hoping the former PM would take it upon himself to withdraw his candidacy in what a leading Shiite figure said would help protect the unity of the coalition.

Leading members of the coalition were hoping to give Maliki enough time to decide himself to withdraw, but as time stretches on, the coalition may take matters into its own hands and take “necessary” choices, said the figure.

Other sources revealed, however, that Maliki refuses to voluntarily withdraw from the race believing that this is a responsibility that should be shouldered by the Framework. This has effectively left the alliance with complex and limited choices to end the crisis.

Sources close to Maliki said he has made light of US threats to impose sanctions, saying that if they were to happen, Iraq will emerge on the other side stronger, citing other countries that came out stronger after enduring years of pressure.

Moreover, he is banking on an American change in position, saying mediators have volunteered to “polish his image before Trump and his team.” Members of Maliki’s State of Law coalition declined to comment on this information.

Sources inside the Framework said the coalition may “ultimately withdraw Maliki’s nomination if he becomes too much of a burden on an already weary alliance.”

Doing so may cost them a strong ally in Maliki and force the Framework to yield to Washington’s will, said the Shiite figure. “Maliki may come off as stubborn and strong, but he is wasting his realistic options at this critical political juncture,” it added.

The Framework is divided between a team that is banking on waiting to see how the US-Iran tensions will play out to resolve the crisis and on Maliki voluntarily withdrawing his nomination. The other team is calling for the coalition to resolve the crisis through an internal vote.

Leading Shiite figures told Asharq Al-Awsat that opponents of Maliki’s nomination in the coalition have no choice but to apply internal pressure inside the Framework, which is on the verge of collapse.