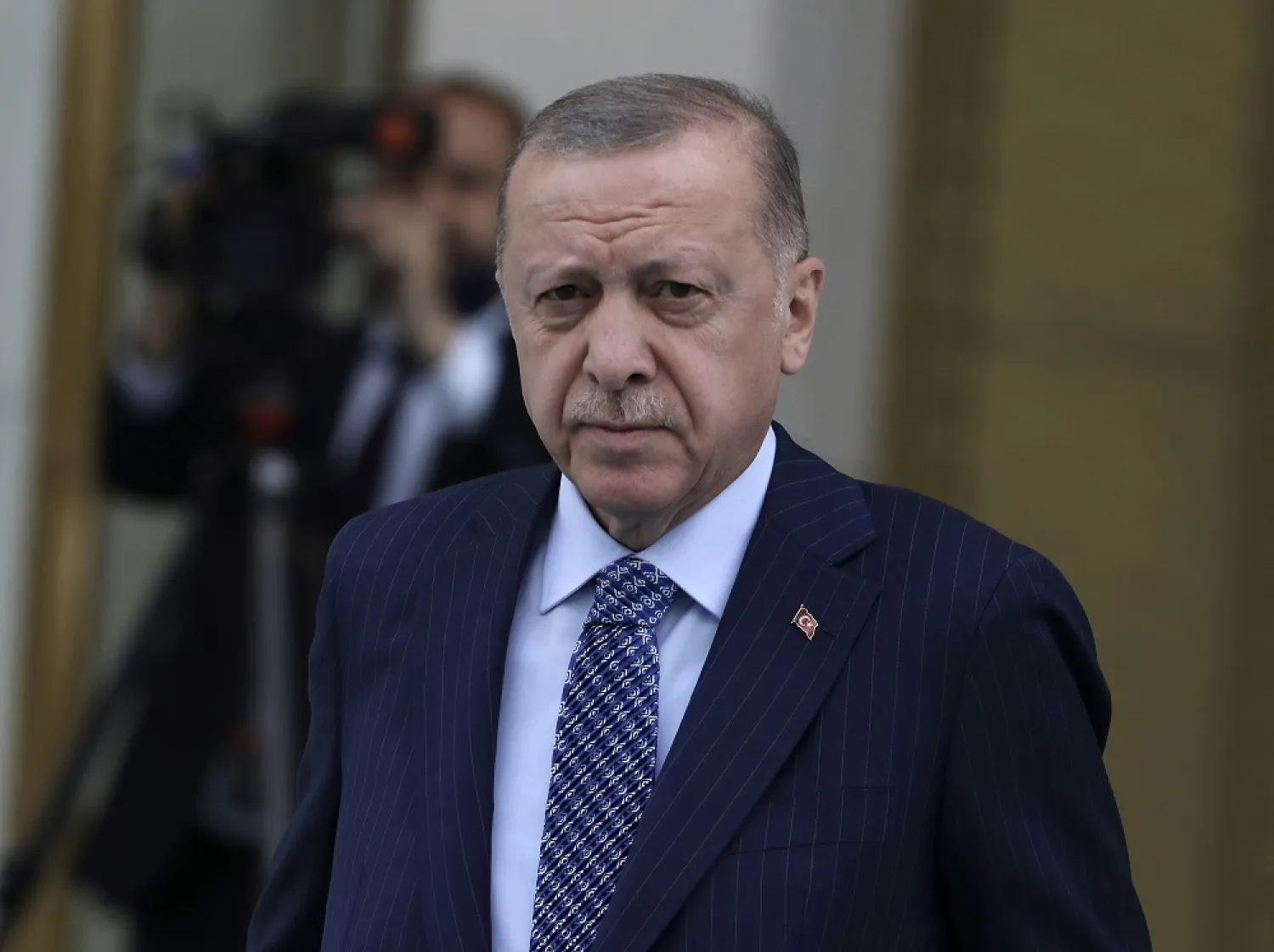

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has thrown a spanner in the works of Sweden and Finland’s historic decisions to seek NATO membership, declaring that he cannot allow them to join due to their alleged support of Kurdish militants and other groups that Ankara says threaten its national security.

NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg has voiced confidence that the alliance will move to admit Sweden and Finland swiftly. But Erdogan's declaration suggests that the two Nordic countries’ path to membership could be anything but smooth.

Turkey’s approval is crucial because the military alliance makes its decisions by consensus. Any of its 30 member countries can veto a new member.

Erdogan’s government is expected to use the two countries’ membership bids as leverage for concessions and guarantees from its allies.

Here’s a look at Turkey’s position, what it could gain and likely repercussions:

What’s Turkey’s problem with the membership bids?

Turkey, which has NATO’s second largest army, has traditionally been supportive of NATO enlargement, believing that the alliance’s "open door" policy enhances European security. It has for example, spoken in favor of the prospect of Ukraine and Georgia joining.

Erdogan’s objection to Sweden and Finland stems from Turkish grievances with Stockholm’s - and to a lesser degree Helsinki’s - perceived support of the banned Kurdistan Workers Party, or PKK, the leftist extremist group DHKP-C and followers of the US-based Muslim cleric Fethullah Gulen who Ankara claims was behind a failed military coup attempt in 2016.

Many Kurdish and other exiles have found refuge in Sweden over the past decades, as have members of Gulen’s movement more recently. According to Turkey’s state-run media, Sweden and Finland have refused to extradite 33 people wanted by Turkey.

Ankara, which frequently accuses allies of turning a blind eye to its security concerns, has also been angered by restrictions on sales of military equipment to Turkey. These were imposed by EU countries, including Sweden and Finland, following Turkey's military incursion into northern Syria in 2019.

Further justifying his objection, Erdogan says his country doesn't want to repeat a "mistake” by Ankara, which agreed to readmit Greece into NATO’s military structure in 1980. He claimed the action had allowed Greece "to take an attitude against Turkey” with NATO’s backing.

What could Turkey gain?

Turkey is expected to seek to negotiate a compromise deal under which the two countries will crack down on the PKK and other groups in return for Turkish support of their joining NATO. A key demand is expected to be that they halt any support to a Syrian Kurdish group, the Kurdish People’s Protection Units, or YPG. The group is a Western ally in the fight against the ISIS group in northern Syria but Turkey views it as an extension of the PKK.

Erdogan could also seek to use Sweden and Finland’s membership to wrest concessions from the United States and other allies. Turkey wants to return to the US-led F-35 fighter jet program - a project it was kicked out of following its purchase of Russian S-400 missile defense systems. Alternatively, Turkey is looking to purchase a new batch of F-16 fighter jets and upgrade its existing fleet.

Other possible demands could include an end to an unofficial embargo on military sales to Turkey by allies; concessions from EU member countries concerning Turkey’s faltered bid to join the bloc; and increased funds to help the country support 3.7 million Syrian refugees.

How does this affect Turkey’s image in the West?

Turkey’s threat of a veto is likely to undermine its own status in Washington and across NATO, reinforcing an image of a country that is blocking the alliance’s expansion for its own profit. With the move, Turkey also risks damaging the credit it had earned by supplying Ukraine with the Bayraktar TB2 armed drones that became an effective weapon against Russian forces.

"There is no scenario under which Turkey does not end up being seen as (Russian President Vladimir) Putin’s mole inside NATO," said Soner Cagaptay, an expert on Turkey at the Washington Institute. "Everybody will forget the objections linked to the PKK. Everybody will focus on the fact that Turkey is blocking NATO’s expansion. It will distort the view of Turkey across (NATO)."

Cagaptay said Turkey’s obstruction could also undo "the positive momentum” that had started to build in Washington regarding the sale of the F-16s. "I cannot see that sale going through at this stage," he said.

Is Turkey trying to appease Russia?

Turkey has built close relations with both Russia and Ukraine and has been trying to balance its ties with both. It has refused to join sanctions against Russia - while supporting Ukraine with the drones that helped deny Russia air superiority.

"The fact that Erdogan is derailing (the NATO) process intentionally suggests that maybe he is trying to balance the strong military support Turkey has given to Kyiv with political support to Russia," Cagaptay said.

A top Turkish politician has also expressed concerns that Finland and Sweden’s membership could provoke Russia and inflame the war in Ukraine. Devlet Bahceli, the leader of a nationalist party allied with Erdogan, said the best option would be to keep the two Nordic countries in the "waiting room."

Can the move help Erdogan’s ratings at home?

The Turkish leader is seeing a decline in his domestic support due to a faltering economy, skyrocketing inflation and a cost of living crisis.

A standoff with Western nations over the emotional issue of perceived support to the PKK could help Erdogan boost his support and rally the nationalist vote before elections that are currently scheduled for June 2023.

"With dwindling domestic support at a time when Turkey is entering a critical electoral cycle, Erdogan is looking for a higher international profile to demonstrate his global importance to Turkish voters," analyst Asli Aydintasbas wrote in an article published in the European Council on Foreign Relations.