The positions of Arab and foreign countries towards the Syrian presidential elections reflect a change in the overall “foreign environment” towards the war-torn country. The elections in turn shed light on the dramatic geographic changes that have taken place in Syria in recent years, the situation of Syrians inside the country and abroad and the changes in government and opposition policies.

In 2012, a year after the eruption of anti-regime protests, a new constitution was adopted for Syria, paving the way for a new way in which elections are held. They transformed them from a referendum to a voting process with several candidates.

Presidential elections were then held in June 2014 in line with the new constitution and the participation of three candidates, including President Bashar Assad.

Western criticism

On May 14, 2014, the foreign ministers of the “Friends of Syria Group” denounced the polls as a farce that “mocks the innocent lives lost in the conflict, utterly contradicts the (2012) Geneva communiqué and is a parody of democracy.”

The meeting was attended by then head of the National Coalition of Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces Ahmed al-Jarba, who was recognized by over a hundred countries as a “representative” of the Syrian people.

The 2014 elections forged ahead in spite of western opposition. They were held exclusively in regions held by the regime. Abroad, they were staged in 39 countries, including nine Arab ones: Iraq, Lebanon, Jordan, Bahrain, Oman, Yemen, Sudan, Algeria and Mauritania. Twelve Arab countries were excluded from the process because Syria does not boast diplomatic representation there.

The United Arab Emirates and European countries refused to hold the elections on their territories.

On June 4, 2014, the Supreme Constitutional Court announced that the voter turnout stood at 73.42 percent. It added that some 11 million out of around 15 million registered voters had taken part in the polls. Assad was declared victor with 88.7 percent of the vote.

On the Arab and international scene, congratulations on the “victory” were sent out by former Algerian President Abdulaziz Bouteflika, the leaders of Armenia, Afghanistan, Belarus, Cuba, Venezuela, South Africa, the Palestinian Authority, Iran, Hezbollah and the BRICS group that includes Russia, Brazil, India, China and South Africa.

The elections drew sharp criticism from western and Arab countries. The G7 would later denounce the “sham” polls, declaring “there is no future for Assad in Syria.” The European Union, NATO, former Arab League chief Nabil al-Arabi and ex-United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon all dismissed the elections.

Silence and mild criticism

Syria has witnessed radical changes in the seven years that have passed since the last presidential polls. The priorities in the region and world have changed as well.

Russia’s intervention in the Syrian conflict in late 2015 shifted the tide in the regime’s favor and Damascus managed to reclaim vast territories from the opposition. The foreign support for the armed groups and political opposition also waned. Syria is now mostly stable after agreements were reached in three “zones of influence”.

Russia managed to pass UN Security Council resolution 2254 that lowered expectations in Syria. Instead of demanding a “transitional ruling authority”, it shifted demands towards “political transition” and constitutional reform. Moscow would then reduce the political process in the constitutional committee that has so far held five meetings in Geneva without reaching a single major breakthrough.

Moscow and Damascus would then later announce that constitutional reform and the presidential elections were two separate issues. Russia would later throw its weight behind Damascus in holding the presidential elections in May 2021. It also encouraged Arab and European countries to “accept the reality”, “normalize” ties with Damascus and contribute in Syria’s reconstruction.

The United States under Donald Trump kept up a “maximum pressure” campaign on Damascus and sought its continued isolation and imposed more sanctions against the regime. Syria is not a priority for the Joe Biden administration.

Marking ten years of conflict in Syria, the European Union and United States in March announced their rejection of the presidential elections. They said the polls should not be used as an excuse to normalize relations with Damascus.

Earlier this month, the G7 said: “In line with resolution 2254, we urge all parties, especially the regime, to engage meaningfully with the inclusive UN-facilitated political process to resolve the conflict, notably the Constitutional Committee, to include the release of detainees and the meaningful participation of women.

“This includes a nationwide ceasefire and a safe and neutral environment to allow for the safe, voluntary and dignified return of refugees. It should pave the way for free and fair elections under UN supervision, ensuring the participation of all Syrians including members of the diaspora.

“Only when a credible political process is firmly under way would we consider assisting with the reconstruction of Syria,” it stressed.

The frontlines in Syria have now effectively stabilized around the three zones of influence, while half of the population has been displaced internally and abroad. Those still in Syria live amid widespread destruction and a deeply changed social and economic environment as the country endures a stifling economic crisis compounded by years of conflict.

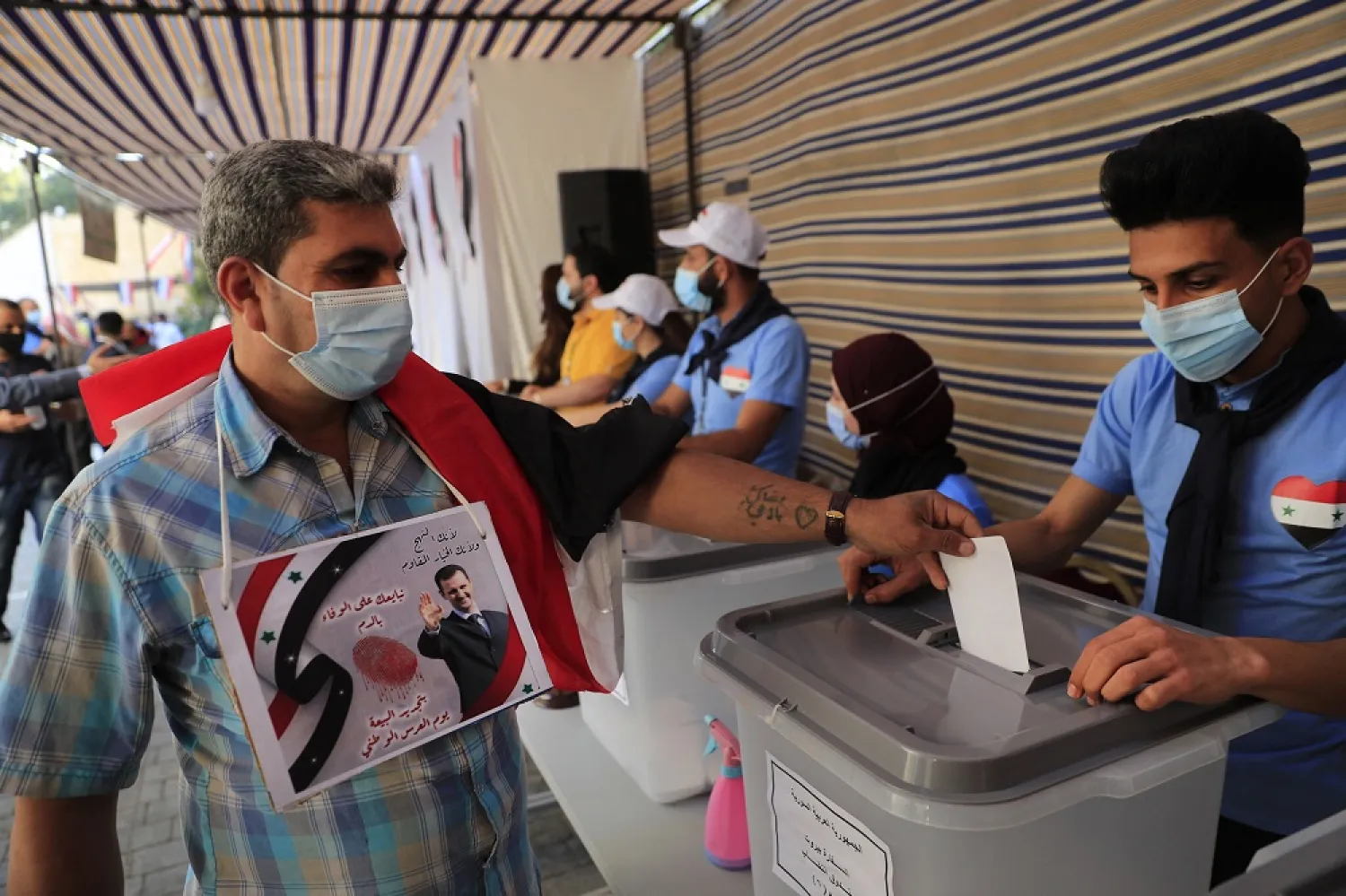

Despite the challenges and criticism, Damascus has insisted on holding the elections. The first stage kicked off on Thursday with voting by Syrians residing abroad. The elections inside Syria will be held on May 26.

Three candidates are in “contention”: Assad, running under the slogan “Hope with work,” Abdullah Salloum Abdullah, under the slogan “Our strength in our unity” and “Yes to defeating the occupiers” and “opposition” candidate Mahmoud Merhi, under the slogan “Together to free prisoners of conscience”.

The government had kicked off electoral campaigns in regions under its control, or about 65 percent of the country.

The Kurdish autonomous administration in the region east of the Euphrates has refused to hold the elections on its territories, except in “security zones” held by the regime. An American delegation had notably visited in recent days the Kurdish-held regions, the first by a US team since Biden came to power, reflecting where his administration’s priorities in Syria lie.

The Hayat Tahrir al-Sham group, which controls northwestern Syria, declared that it was “bolstering institutions” and refused to hold elections in its regions.

Arab countries and the Arab League have not announced any positions ahead of the elections. Western countries and allies of the Syrian opposition were also focused on the “correct standards of the elections”, failing to mention the current polls.

The United Nations has also kept mum on the elections, as have the UAE, France, Arab and foreign countries that have allowed the voting to take place on their territories.

European diplomats are set to visit Damascus while the elections are underway. The polls will be “monitored” by representatives of countries that are allied to Damascus.

All of the above are factors to keep in mind when the elections results are declared at the end of the month. Other questions will follow, such as: What position will Arab countries adopt when Assad is declared the winner? Who will congratulate him? What about western countries? Will they remain united? What about the United States? How will the result impact the UN’s role in sponsoring the political process and constitutional reform? To what degree will Russia consider the elections a “turning point in opening a new chapter” between the Arabs and Europe with Damascus? What of the Syrians, their suffering and divisions?