It’s unwise to corner Saddam Hussein and force him to accept a partner in governing Iraq. The Baath Party and Saddam himself don't favor partnerships.

The Baath Party, which regained power on July 17, 1968, has a history of significant and costly turning points.

The first major shift came on July 30 that year, enabling the party to consolidate power under President Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr, with Saddam as his deputy.

As a journalist, I spoke with some key figures from that time and felt it was important to share their stories with the readers of Asharq Al-Awsat.

The defeat of Arab armies in the 1967 war enraged the Arab public, who blamed their governments for what was termed a “setback” but was really a disaster.

Iraqi President Abdul Rahman Arif, who had succeeded his brother Abdul Salam, appeared weak, with a loose grip on the military and little popular support.

By the spring of 1968, rumors were spreading in closed circles about various factions plotting to seize power. Some expected the country to fall under military control.

The Baath Party leadership was keeping a close watch, fearing a coup. They began planning a return to power, seeking to avenge the 1963 events that led to bloodshed and the ousting of Abdul Salam Arif, whom they had initially helped bring to power.

The leadership wanted to avoid a violent takeover and carefully considered their strategy.

A key figure was Col. Ibrahim al-Daoud, commander of the 20,000-strong Republican Guard. If al-Daoud resisted, a bloody battle could ensue at the palace gates. There was also the risk that such a conflict might pave the way for a third faction from the military to step in as a savior.

The Baathists decided to approach al-Daoud, hoping to win him over or at least neutralize him. They noted that al-Daoud was heavily influenced by his friend Abdul Razzaq al-Nayef, the deputy director of military intelligence, known for his strong influence and rumored ties to Western intelligence. Al-Daoud was thought to follow al-Nayef’s lead closely.

The complex task required cunning and was entrusted to al-Bakr, known for his military skills and political savvy.

The coup organizers secured the cooperation of officer Saadoun Ghaidan, who commanded a force stationed at the presidential palace, including several tanks.

Al-Bakr met with al-Daoud to reveal the plan to overthrow Arif. He urged him to keep the matter secret, swearing on the Quran that it would not be shared with anyone else, especially al-Nayef. However, al-Daoud quickly informed al-Nayef on July 15.

This leak put the Baath Party leadership in a tough spot. The secret was out, and al-Nayef, a man considered dangerous and rumored to have suspicious ties with Western intelligence, knew their plans. The success or failure of the coup now depended on his actions.

Salah Omar al-Ali, a key figure in the leadership, explained: “On the morning of July 16, we informed the civilian and military groups involved about the final details of their roles.”

“We initially planned to act on July 14, the anniversary of the 1958 revolution that established the republic, but practical issues delayed us.”

“On July 16, we retrieved hidden weapons and military uniforms for disguise. At 8 p.m., we met at al-Bakr’s house in the Ali al-Salih neighborhood on 14 Ramadan Street to finalize our plans, waiting for the operation at 2:30 a.m. Then, the unexpected happened.”

Shocking message

As the Baath Party’s regional leaders were finalizing their plans, there was a knock at the door. Al-Bakr answered and came back with a small note. He announced that it was from al-Nayef. The message read: “I know about your operation. I support you and am ready to help in any way. Trust in God.”

Al-Ali recalled that al-Bakr presented the message to the group, saying: “We need to discuss this and make a decision.”

The note, delivered by a lieutenant serving as al-Nayef’s aide, was shocking.

Although the messenger was a Baathist, his actions didn’t lessen the severity of the situation.

The group grew anxious and confused. Al-Nayef was known to be strong, very intelligent and ambitious, which made him a formidable figure. They considered the risks: if they canceled the operation, al-Nayef might reveal their plans, seeing it as a slight against him.

Canceling could be disastrous for the party, but involving al-Nayef was risky too. It was clear that al-Daoud had not kept his oath, complicating matters.

They ultimately decided to proceed and sent al-Nayef this message: “We intentionally kept you uninformed due to your sensitive position and concern for your safety. We informed Ibrahim al-Daoud to avoid putting you in an awkward position, knowing he would tell you. We are moving forward with the operation, and if successful, you will be Iraq’s Prime Minister, God willing.”

Essentially, they made two decisions: to entice al-Nayef with the prime ministership and to eliminate al-Nayef and al-Daoud as soon as possible. The task of storming the Republican Palace was given to the party’s regional leaders.

Before the operation, they gathered at the home of Abdul Karim al-Nadda, al-Bakr’s brother-in-law, who worked for the railway and lived near the radio station in the Salhiya area.

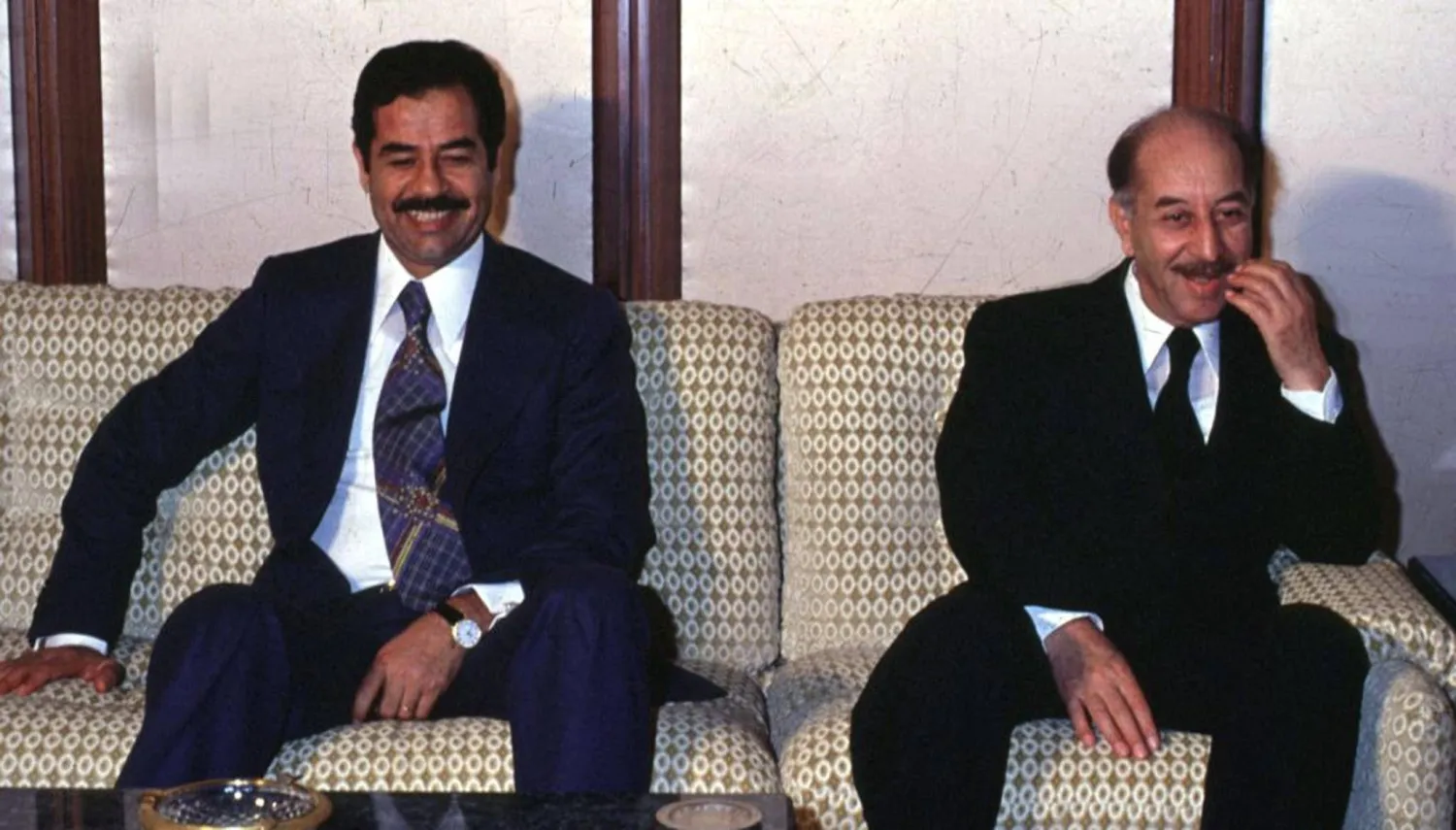

The emotions were high as the nine leadership members, including al-Bakr and Saddam, met with others, including Hardan al-Tikriti. The total number present was less than twenty. The plan required al-Daoud and Ghaidan to be waiting for them.

Storming the palace

The team put on military uniforms and officer badges. At the planned time, a military truck arrived, and they climbed aboard, while another group took two civilian cars. They reached the palace entrance dressed in their military gear and carrying rifles. Ghaidan was waiting at the tank battalion entrance and opened the gate for them. Several young party members, who had secretly trained to operate tanks, joined them.

They were surprised to find that the tanks around the palace were modern and the trainees had trouble operating them. Fortunately, one young man managed to start a tank and moved from one to another, helping them complete the encirclement of the palace.

They set up their command post at the tank battalion headquarters. Al-Bakr called Abdul Rahman Arif, who was asleep. The two men knew each other well. Surprised, Arif asked, “What’s going on?” Al-Bakr responded: “The revolutionary leadership has taken control of the country.”

“Please surrender to avoid any conflict. We guarantee your safety and that of your family. This is not a personal attack; it’s to prevent further bloodshed under your weak leadership. Surrender now.”

Finding the situation serious, Arif tried contacting division commanders outside Baghdad but got no response. Ten minutes later, al-Bakr called again, insisting Arif surrender. In a final warning, al-Bakr said: “If you don’t surrender, you’ll be responsible for your and your family’s safety.”

To reinforce the message, they fired artillery shells over the palace. Hearing this, Arif realized there was no negotiating and contacted them to arrange his surrender. Arif came out and was taken in a small military vehicle to the tank battalion headquarters.

At the start of the operation, a team was dispatched to arrest Prime Minister Taher Yahya at his home. This move marked the Baath Party’s return to power, achieved without any bloodshed.

Potential threats

When asked about Saddam Hussein’s actions during those crucial hours, al-Ali said: “Saddam acted just like the others; he wore a military uniform and carried a rifle, following the lead of the other party members.”

Despite his many criticisms today, Saddam’s bravery and ruthlessness were clear. At the time, he was not a dominant figure and did not control decisions. He was a loyal party member who followed orders.

After the Baath Party took power, its leaders saw Prime Minister al-Nayef and Defense Minister al-Daoud as potential threats.

Al-Ali, involved in the plot against them, described the situation: “We held a meeting to discuss our decisions, including removing al-Nayef and al-Daoud. Al-Bakr said we had to include al-Nayef because he knew our plan and could have turned against us. We promised him the prime ministership, and he did not betray us.”

“However, I was concerned that removing al-Nayef might be seen as treachery, given the bloody history with the Communists in 1963. I suggested we keep cooperating with him and reassess if his behavior changed. We agreed, and al-Nayef began his role as prime minister.”

A few days later, al-Bakr called an urgent meeting and urged the leadership to quickly remove al-Nayef. He explained that he was rapidly working against the party and had recruited military officers without realizing some were Baathists.

“Act fast before he can undermine us,” al-Bakr warned. “Plan his removal, and I’ll support whatever you decide.”

The next day, we met at the home of Saleh Mahdi Al-Ammash, the Interior Minister, since we feared al-Nayef might trap us if he knew our plans. We decided to remove both al-Nayef and al-Daoud.

We had military units in Jordan. We planned for al-Daoud to inspect them while secretly sending party members to arrest him and send him to Spain. At the same time, we would act against al-Nayef.

On July 30, al-Daoud was captured and sent to Spain. Meanwhile, we targeted al-Nayef. After lunch at the palace, he went to al-Bakr’s office. Saddam and I entered with rifles and demanded his surrender. At first, he resisted but then begged us, citing his family.

We needed to act quickly and discreetly. We told al-Nayef to leave as if nothing had happened and warned him not to signal his guards. He was escorted to a car by Saddam, who warned him not to resist. The car left through a rear gate, and al-Nayef was flown out to Morocco.