Allegations of research fakery at a leading cancer center have turned a spotlight on scientific integrity and the amateur sleuths uncovering image manipulation in published research.

Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, a Harvard Medical School affiliate, announced Jan. 22 it's requesting retractions and corrections of scientific papers after a British blogger flagged problems in early January.

The blogger, 32-year-old Sholto David, of Pontypridd, Wales, is a scientist-sleuth who detects cut-and-paste image manipulation in published scientific papers.

He's not the only hobbyist poking through pixels. Other champions of scientific integrity are keeping researchers and science journals on their toes. They use special software, oversize computer monitors and their eagle eyes to find flipped, duplicated and stretched images, along with potential plagiarism, The Associated Press reported.

A look at the situation at Dana-Farber and the sleuths hunting sloppy errors and outright fabrications:

WHAT HAPPENED AT DANA-FARBER?

In a Jan. 2 blog post, Sholto David presented suspicious images from more than 30 published papers by four Dana-Farber scientists, including CEO Laurie Glimcher and COO William Hahn.

Many images appeared to have duplicated segments that would make the scientists' results look stronger. The papers under scrutiny involve lab research on the workings of cells. One involved samples from bone marrow from human volunteers.

The blog post included problems spotted by David and others previously exposed by sleuths on PubPeer, a site that allows anonymous comments on scientific papers.

Student journalists at The Harvard Crimson covered the story on Jan. 12, followed by reports in other news media. Sharpening the attention was the recent plagiarism investigation involving former Harvard president Claudine Gay, who resigned early this year.

HOW DID DANA-FARBER RESPOND?

Dana-Farber said it already had been looking into some of the problems before the blog post. By Jan. 22, the institution said it was in the process of requesting six retractions of published research and that another 31 papers warranted corrections.

Retractions are serious. When a journal retracts an article that usually means the research is so severely flawed that the findings are no longer reliable.

Dr. Barrett Rollins, research integrity officer at Dana-Farber, said in a statement: “Following the usual practice at Dana-Farber to review any potential data error and make corrections when warranted, the institution and its scientists already have taken prompt and decisive action in 97 percent of the cases that had been flagged by blogger Sholto David."

WHO ARE THE SLEUTHS?

California microbiologist Elisabeth Bik, 57, has been sleuthing for a decade. Based on her work, scientific journals have retracted 1,133 articles, corrected 1,017 others and printed 153 expressions of concern, according to a spreadsheet where she tracks what happens after she reports problems.

She has found doctored images of bacteria, cell cultures and western blots, a lab technique for detecting proteins.

“Science should be about finding the truth,” Bik told The Associated Press. She published an analysis in the American Society for Microbiology in 2016: Of more than 20,000 peer-reviewed papers, nearly 4% had image problems, about half where the manipulation seemed intentional.

Bik's work brings donations from Patreon subscribers of about $2,300 per month and occasional honoraria from speaking engagements. David told AP his Patreon income recently picked up to $216 per month.

Technology has made it easier to root out image manipulation and plagiarism, said New York University science educator Ivan Oransky, co-founder of the Retraction Watch blog. The sleuths download scientific papers and use software tools to help find problems.

Others doing the investigative work remain anonymous and post their findings under pseudonyms. Together, they have “changed the equation” in scientific publication, Oransky said.

“They want science to be and do better,” Oransky said. “And they are frustrated by how uninterested most people in academia — and certainly in publishing — are in correcting the record.” They're also concerned about the erosion of public trust in science. WHAT MOTIVATES MISCONDUCT?

Bik said some mistakes could be sloppy errors where images were mislabeled or “somebody just grabbed the wrong photo.”

But some images are obviously altered with sections duplicated or rotated or flipped. Scientists building their careers or seeking tenure face pressure to get published. Some may intentionally falsify data, knowing that the process of peer review — when a journal sends a manuscript to experts for comments — is unlikely to catch fakery.

“At the end of the day, the motivation is to get published,” Oransky said. “When the images don’t match the story you’re trying to tell, you beautify them.”

WHAT HAPPENS NEXT?

Scientific journals investigate errors brought to their attention but usually keep their processes confidential until they take action with a retraction or correction.

Some journals told the AP they are aware of the concerns raised by David's blog post and were looking into the matter.

Science Sleuths Using Technology to Find Fakery, Plagiarism in Published Research

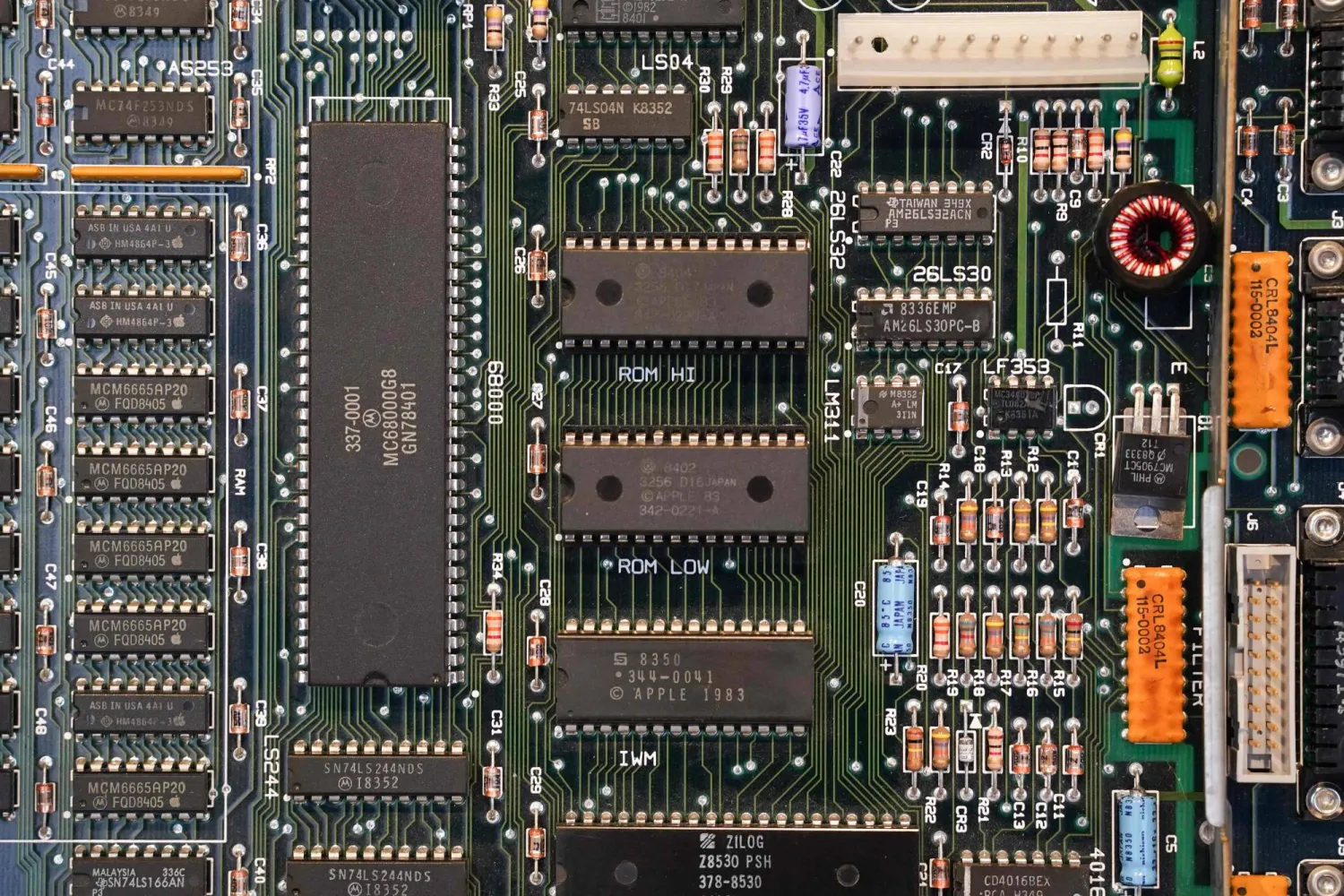

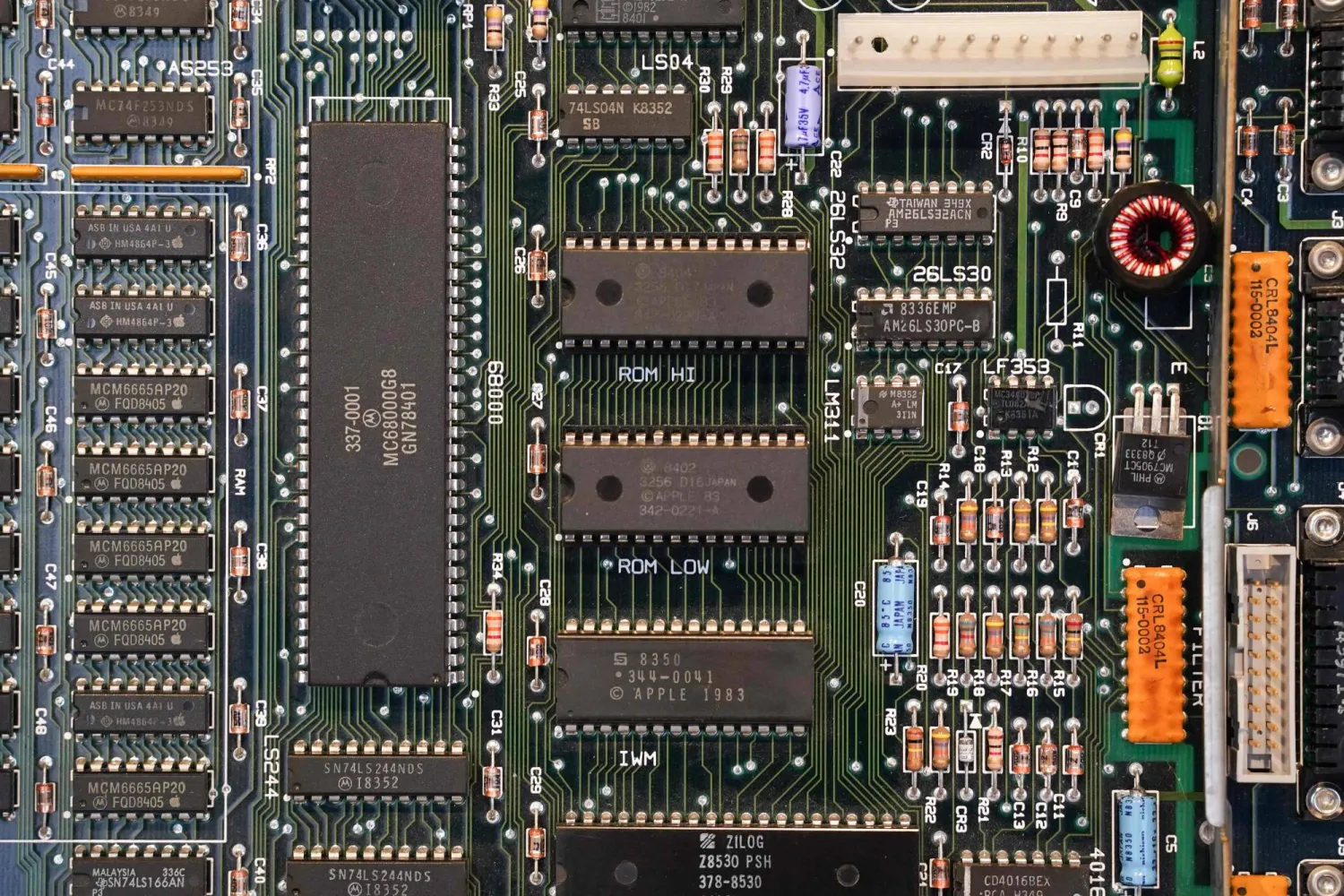

Part of an early model central processing unit is seen on display at the Computer History Museum on January 19, 2024 in Mountain View, California, as the museum celebrates Mac's 40th birthday. (Photo by Loren Elliott / AFP)

Science Sleuths Using Technology to Find Fakery, Plagiarism in Published Research

Part of an early model central processing unit is seen on display at the Computer History Museum on January 19, 2024 in Mountain View, California, as the museum celebrates Mac's 40th birthday. (Photo by Loren Elliott / AFP)

لم تشترك بعد

انشئ حساباً خاصاً بك لتحصل على أخبار مخصصة لك ولتتمتع بخاصية حفظ المقالات وتتلقى نشراتنا البريدية المتنوعة