Three decades ago, Maria Ines Suarez was living in a neighborhood that residents of the Colombian city of Medellin knew as "the rubbish dump."

The 68-year-old woman recalls: “I shared a one-room shack with my five children. We washed in a well and used candles for light. We rummaged through garbage for food.”

According to a report published by the German news agency (dpa), the retired domestic worker now lives in a comfortable house in a neighborhood created by and named after her benefactor, the late drug lord Pablo Escobar, one of the most violent criminals in history, whom local residents revere almost as a saint.

"Many people keep his picture in their homes and light candles for him," Yamile Zapata says at her hairdressing salon near an outdoor wall painting paying tribute to Escobar.

The Drug Lord had donated houses to about 400 poor families in the area while trying to launch a political career in the 1980s.

Twenty-four years after "the Boss" was gunned down by police, or, as many believe in Medellin, shot himself in the ear while being besieged on a rooftop, at age 44, his figure still seems omnipresent in Colombia's second-largest city.

"His hitmen killed my uncle. He did nothing good, only made poor children dream of having a gun and a motorbike, instead of wanting to study," said Sebastian Lopez, a tourism company employee.

Many people in Medellin tell stories about relatives or acquaintances who associated with or were killed by the Medellin cartel headed by Escobar.

He dominated cocaine trade to the United States and earned him a fortune worth tens of billions of dollars.

He bombed a plane he mistakenly believed to carry another presidential candidate in 1989, blew up secret police headquarters and nearly toppled the government through assassinations, bribes and bombings aimed at intimidating it into submission.

Many houses in Medellin are still believed to hide Escobar's drug money inside their walls.

Interest in Escobar has only been increased by local Colombian television series and hit Netflix show "Narcos."

About half a dozen tourism operators now taking dozens of visitors to see places associated with the drug lord almost daily.

The sights include a white multi-storey building called Monaco, one of Escobar's residences, which was once bombed by the rival Cali drug cartel. The local authorities have left the building in police custody, unsure what to do with it.

Further away, on a green hillside where Escobar built a luxury prison for himself, residents of an elderly people's home that now operates there stroll in the garden.

The "prison" grounds contain a helicopter pad, a building where Colombia's top football teams came to play for Escobar, and a chapel with a statue of the crucified Christ surrounded by golden guns.

"The administrators here pretend the statue was brought in by local priests, because they don't want the place to be associated with Pablo Escobar," a tourism guide says.

Escobar's grave at the Montesacro cemetery has meanwhile become a site of pilgrimage. "People come here daily to pray and ask him for help," says Federico Arrollave, a cemetery employee known as "the angel" guarding the grave covered with flowers.

"Pablo is making more money dead than alive" for Medellin through the tourism industry, jokes Escobar's brother Roberto Escobar, who served 14 years in prison and now runs a museum in one of Pablo's former houses.

Museum employees refer to the drug lord respectfully as "Don Pablo," to his hitmen as "the boys," describe him as a Robin Hood who dished out money to the poor, and even claim that he "wanted to finish with corruption."

Medellin Mayor Federico Gutierrez is anything but pleased with the tourism industry booming around Escobar in the city taking pride in its Metro train and environmental policies.

He issued a public letter criticizing a Panama travel agency for advertising "narco tours" in 2016 and lashed out at U.S. Rapper Wiz Khalifa, who visited the grave in Montesacro in March.

"One really notices how this guy has not had to suffer from the violence of these drug traffickers. This shameless man, instead of taking flowers to Pablo Escobar, should have taken flowers to the victims, and owes an apology to the city," Gutierrez said.

Cocaine trafficking continues in Colombia, where the surface of illegal coca fields increased by up to 50% to up to 150,000 hectares in 2016, according to the newspaper El Tiempo.

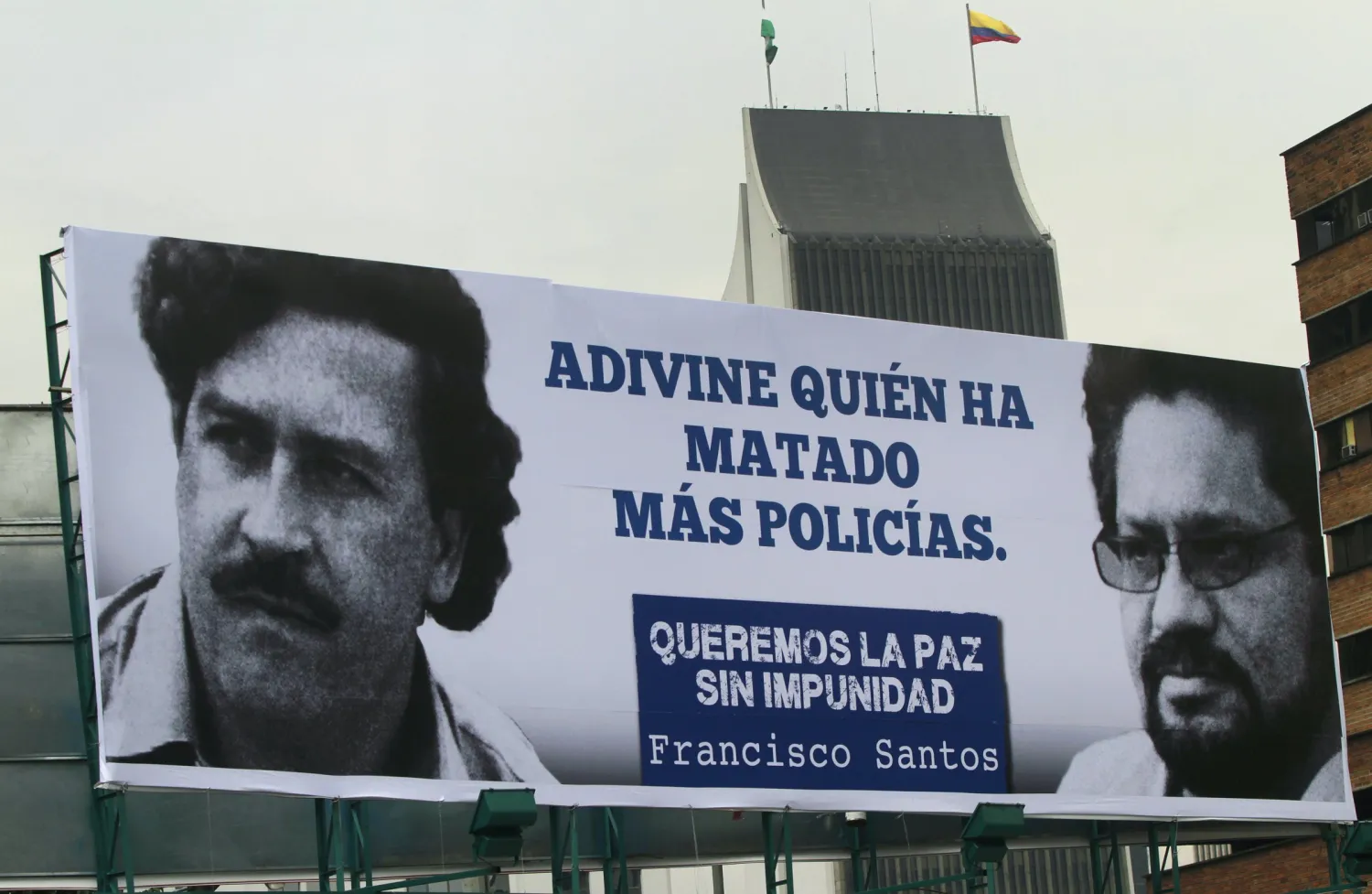

The growth has continued despite a peace deal that the government signed in November 2016 with the guerrilla movement FARC, which was involved in the drug trade.