Syrian security officers hung Muhannad Ghabbash from his wrists for hours, beat him bloody, shocked him with electricity and stuck a gun in his mouth.

Ghabbash, a law student from Aleppo, repeatedly confessed his actual offense: organizing peaceful anti-government protests. But the torture continued for 12 days, until he wrote a fictional confession to planning a bombing.

That, he said, was just the beginning.

He was flown to a crammed prison at Mezze air base in Damascus, the Syrian capital, where he said guards hung him and other detainees from a fence naked, spraying them with water on cold nights. To entertain colleagues over dinner, he and other survivors said, an officer calling himself Hitler forced prisoners to act the roles of dogs, donkeys and cats, beating those who failed to bark or bray correctly.

In a military hospital, he said, he watched a nurse bash the face of an amputee who begged for painkillers. In yet another prison, he counted 19 cellmates who died from disease, torture and neglect in a single month.

“I was among the lucky,” said Ghabbash, 31, who survived 19 months in detention until a judge was bribed to free him.

As Syrian regime leader Bashar Assad closes in on victory over an eight-year revolt, a secret, industrial-scale system of arbitrary arrests and torture prisons has been pivotal to his success. While the military, backed by Russia and Iran, fought armed rebels for territory, the regime waged a ruthless war on civilians, throwing hundreds of thousands into filthy dungeons where thousands were tortured and killed.

Nearly 128,000 have never emerged, and are presumed to be either dead or still in custody, according to the Syrian Network for Human Rights, an independent monitoring group that keeps the most rigorous tally. Nearly 14,000 were “killed under torture.” Many prisoners die from conditions so dire that a United Nations investigation labeled the process “extermination.”

Now, even as the war winds down, the world’s attention fades and countries start to normalize relations with Syria, the pace of new arrests, torture and execution is increasing. The numbers peaked in the conflict’s bloodiest early years, but last year the Syrian Network recorded 5,607 new arrests that it classifies as arbitrary — more than 100 per week and nearly 25 percent more than the year before.

Detainees have recently smuggled out warnings that hundreds are being sent to an execution site, Saydnaya Prison, and newly released prisoners report that killings there are accelerating.

Kidnappings and killings by ISIS captured more attention in the West, but the Syrian prison system has vacuumed up many more times the number of people detained by ISIS in Syria. Regime detention accounts for around 90 percent of the disappearances tallied by the Syrian Network.

The regime has denied the existence of systematic abuse.

However, newly discovered regime memos show that Syrian officials who report directly to Assad ordered mass detentions and knew of atrocities.

War crimes investigators with the nonprofit Commission for International Justice and Accountability have found regime memos ordering crackdowns and discussing deaths in detention. The memos were signed by top security officials, including members of the Central Crisis Management Committee, which reports directly to Assad.

A military intelligence memo acknowledges deaths from torture and filthy conditions. Other memos report deaths of detainees, some later identified among photos of thousands of prisoner corpses smuggled out by a military police defector. Two memos authorize “harsh” treatment of specific detainees.

A memo from the head of military intelligence, Rafiq Shehadeh, suggests that officials feared future prosecution: It orders officers to report all deaths to him and take steps to ensure “judicial immunity” for security officials.

Over seven years, The New York Times has interviewed dozens of survivors and relatives of dead and missing detainees, reviewed regime documents detailing prison deaths and crackdowns on dissent, and examined hundreds of pages of witness testimony in human rights reports and court filings.

The survivors’ accounts reported here align with accounts from other prisoners held in the same jails, and are supported by the regime memos and by photos smuggled out of Syrian prisons.

The prison system was integral to Assad’s war effort, crushing the civil protest movement and driving the opposition into an armed conflict it could not win.

In recent months, Syria’s regime has tacitly acknowledged that hundreds of people have died in detention. Under pressure from Moscow, Damascus has confirmed the deaths of at least several hundred people in custody by issuing death certificates or listing them as dead in family registration files. The Syrian Network’s founder, Fadel Abdul Ghany, said the move sent citizens a clear message: “We won, we did this, and no one will punish us.”

There is little hope for holding top officials accountable anytime soon. But there is a growing movement to seek justice through European courts. French and German prosecutors have arrested three former security officials and issued international arrest warrants for Syria’s national security chief, Ali Mamlouk; its Air Force Intelligence director, Jamil Hassan; and others for torture and deaths in prison of citizens or residents of those countries.

Yet Assad and his lieutenants remain in power, safe from arrest, protected by Russia with its military might and its veto in the United Nations Security Council. At the same time, Arab states are restoring relations with Damascus and European countries are considering following suit. US President Donald Trump’s planned pullout of most of the 2,000 American troops in eastern Syria reduces already-minimal American leverage in the conflict, now in its ninth year.

An expanding gulag

The Syrian detention system is a supersized version of the one built by Assad’s father, President Hafez Assad. In 1982, he crushed an armed Muslim Brotherhood uprising in Hama, leveling much of the city and arresting tens of thousands of people: Islamists, leftist dissidents and random Syrians.

Over two decades, around 17,000 detainees disappeared into a system with a torture repertoire that borrowed from French colonialists, regional dictators and even Nazis.

When Bashar Assad succeeded his father in 2000, he kept the detention system in place.

Each of Syria’s four intelligence agencies — military, political, air force and state security — has local branches across Syria. Most have their own jails. CIJA has documented hundreds of them.

It was the detention and torture of several teenagers in March 2011, for scrawling graffiti critical of Assad, that pushed Syrians to join the uprisings then sweeping Arab countries. Demonstrations protesting their treatment spread from their hometown, Daraa, leading to more arrests, which galvanized more protests.

A flood of detainees from all over Syria joined the existing dissidents at Saydnaya Prison. The new detainees ranged “from the garbageman to the peasant to the engineer to the doctor, all classes of Syrians,” said Riyad Avlar, a Turkish citizen who was held for 20 years after being arrested in 1996, as a 19-year-old student, for interviewing Syrians about a prison massacre.

Torture increased, he said; the newcomers were sexually assaulted, beaten on the genitals, and forced to beat or even kill one another.

No one knows exactly how many Syrians have passed through the system since; rights groups estimate hundreds of thousands to a million. Damascus does not release prison data.

By all accounts, the system overflowed. Some political detainees landed in regular prisons. Security forces and pro-regime militias created uncounted makeshift dungeons at schools, stadiums, offices, military bases and checkpoints.

The Syrian Network’s tally of 127,916 people currently caught in the system is probably an under-count. The number, a count of arrests reported by detainees’ families and other witnesses, does not include people later released or confirmed dead.

Because of regime secrecy, no one knows how many have died in custody, but thousands of deaths were recorded in memos and photographs.

A former military police officer, known only as Caesar to protect his safety, had the job of photographing corpses. He fled Syria with pictures of at least 6,700 corpses, bone-thin and battered, which shocked the world when they emerged in 2014.

But he also photographed memos on his boss’s desk reporting deaths to superiors.

Like the death certificates issued recently, the memos list the cause of death as “cardiac arrest.” One memo identifies a detainee who also appears in one of Caesar’s photos; his eye is gouged out.

The prisons seem to have been hit with an uncanny epidemic of heart disease, said Darwish, the human rights lawyer. “Of course, when they die, their heart stops,” he said.

A tour of torture

Ghabbash, the protest organizer from Aleppo, survived torture at at least 12 facilities, making him, he says, “a tour guide” to the system. His odyssey began in 2011, when he was 22. The oldest son of a government building contractor, he was inspired by peaceful protests in the Damascus suburb of Darayya to organize demonstrations in Aleppo.

He was arrested in June 2011, and released after pledging to stop protesting.

“I didn’t stop,” he recalled with a grin.

In August, he was arrested again — the same week that, a memo from CIJA shows, Assad’s top officials ordered a tougher crackdown, criticizing provincial authorities’ “laxness” and calling for more arrests of “those who are inciting people to demonstrate.”

Ghabbash was hung up, beaten and whipped in a string of military and general intelligence facilities, he said. His captors eventually let him go with a stern recommendation given to many similar youths: Leave the country.

Even as they released Saydnaya Prison’s most radical long-term prisoners, Islamists who would later lead rebel groups, they aimed to get rid of civilian opposition. Both moves, critics say, appear to have been part of a strategy to shift the uprising to the battlefield, where Assad and his allies enjoyed a military advantage.

With like-minded civilians fleeing or jailed, and security forces firing on protesters, Ghabbash struggled to dissuade allies from taking up arms and playing into the regime’s hands.

Surreal punishment

In March 2012, Ghabbash was flown to Mezze military air base, named for a well-off Damascus neighborhood nearby.

By then, he and numerous survivors said, there was an industrial-scale transportation system among prisons. Detainees were tortured on each leg of their journeys, in helicopters, buses, cargo planes. Some recalled riding for hours in trucks normally used for animal carcasses, hanging by one arm, chained to meat hooks. Ghabbash’s new cell was typical: 12 feet long, 9 feet wide, usually packed so tightly that prisoners had to sleep in shifts.

Outside the cell, a man was blindfolded and handcuffed in the corridor. It was Darwish, the human rights lawyer. He had been singled out for lecturing a judge on Syrian laws guaranteeing fair trials.

He later ticked off his punishment: “Naked, no water, no sleep, forced to drink my pee.”

Prison torture grew more brutal and baroque as rebels outside made advances and regime warplanes bombed restive neighborhoods. Survivors describe sadistic treatment, rape, summary executions or detainees left to die of untreated wounds and illnesses.

Ghabbash soon got his own special punishment. He was interrogated by a man calling himself Suhail Hassan — possibly Suhail Hassan Zamam, who headed Air Force prisons, according to a leaked regime database — who asked how Ghabbash would solve the conflict.

“Real elections,” he recalled replying. “The people just wanted some reforms, but you used force. The problem is either we have to be with you or you kill us.”

That won him a month of extra torture, the most bizarre in his ordeal.

A guard who called himself Hitler would organize sadistic dinner entertainment for his colleagues. He brought arak and water pipes, Ghabbash said, “to prepare the ambiance.” He made some prisoners kneel, becoming tables or chairs. Others played animals. “Hitler” reinforced stage directions with beatings.

“The dog has to bark, the cat meow, the rooster crow,” Ghabbash said. “Hitler tries to tame them. When he pets one dog, the other dog should act jealous.”

Rampant infection, rotten food

Torture aside, unhealthy detention conditions are so extreme and systemic that a United Nations report said they amounted to extermination, a crime against humanity.

Many cells lack toilets, former prisoners said. Prisoners get seconds per day in latrines, they said; with rampant diarrhea and urinary infections, they relieve themselves in crowded cells. Most meals are a few bites of rotten, dirty food. Some prisoners die from sheer psychological collapse. Most medicine is withheld, injuries left untreated.

Mounir Fakir is 39, but after his ordeal in Mezze, Saydnaya and elsewhere, he looks at least a decade older. A veteran dissident, he said he was arrested on his way to a meeting of the nonviolent opposition. Before-and-after photos show the toll: A hefty man, he was released so emaciated that his wife did not recognize him.

In Saydnaya, cold was the punishment for talking or “sleeping without permission,” Fakir recalled over steaming herbal tea in an Istanbul cafe. Once for more than a month, all of his cellmates’ blankets and clothes were confiscated; they slept naked in freezing temperatures. Sometimes, he said, they were denied water. They tried to wash themselves by scrubbing their skin with sand that ants unearthed from floor cracks.

The day we met, Fakir was marking the anniversary of the death of a cellmate felled by an untreated tooth infection, his jaw swollen almost to the size of “another head.”

Yet “treatment” can also be deadly. Torture and murder take place in hospitals where, on other wings, dignitaries visit wounded officers, said Fakir, other survivors and defectors.

Fakir was taken twice to Military Hospital 601, a colonial-era building with high ceilings and views of Damascus. Up to six prisoners were chained naked to each bed.

“Sometimes one dies and it becomes less,” he said. “Sometimes we want him to die, to take his clothes.”

Once, he said, he watched staff withhold insulin from a diabetic — a 20-year-old waiter — until he died.

Names written in blood

Detainees and defectors have risked their lives to tell their families, and the world, of their plight.

In the Fourth Division dungeon, several detainees decided to smuggle out the names of every prisoner they could identify.

“Even though we are three stories underground, still we can continue our work,” recalled one, Mansour Omari, who was arrested while working for a local human rights organization.

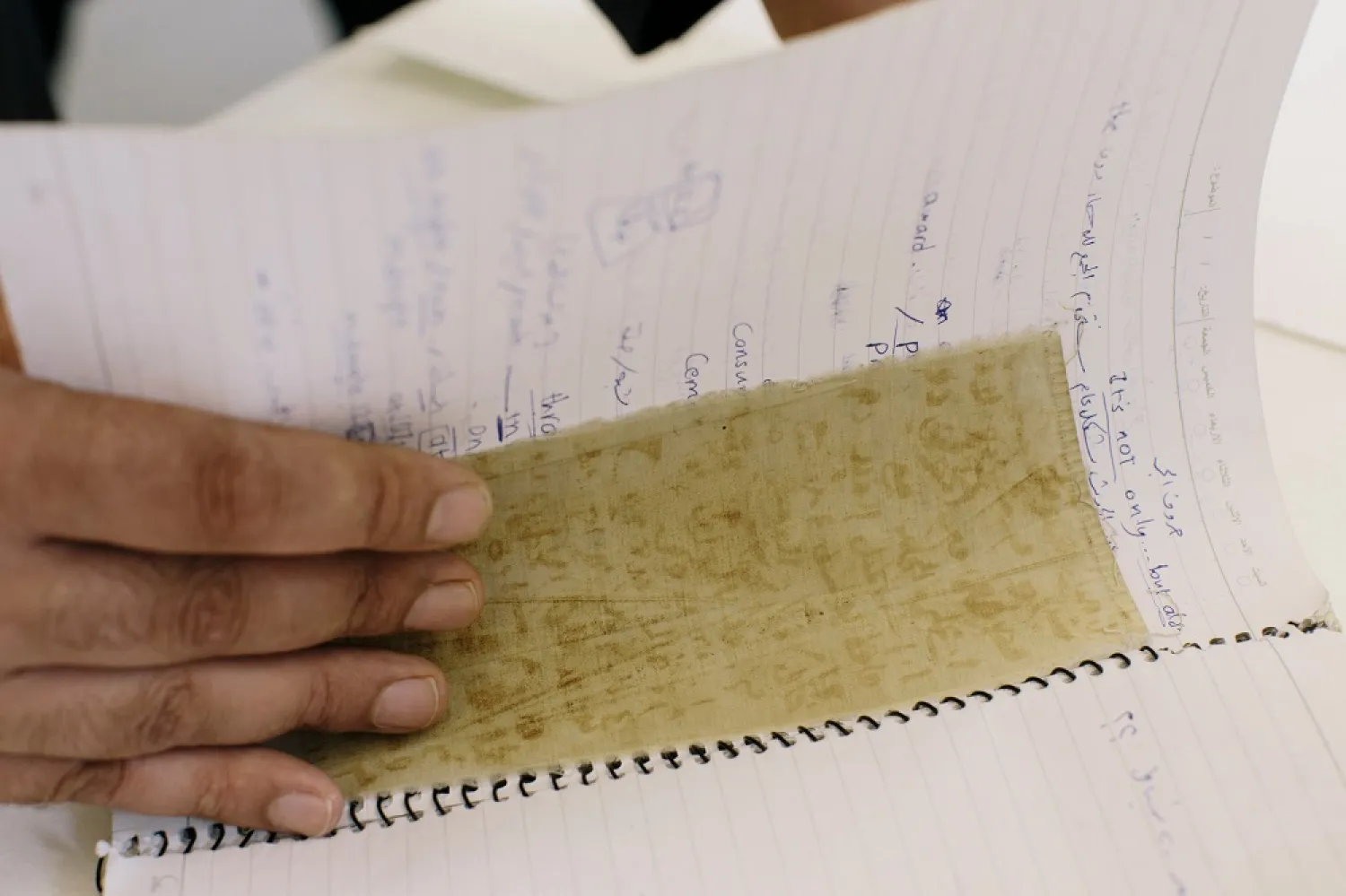

Another detainee, Nabil Shurbaji — a journalist who, by coincidence, was the first to inspire Ghabbash to activism in 2011 and later shared his cell in Mezze — tried to write on cloth scraps with tomato paste. Too faint. Shurbaji finally used the detainees’ own blood, from their malnourished gums, mixed with rust. A detained tailor sewed the scraps into Omari’s shirt. He smuggled them out.

The message in blood reached Western capitals; the shirt scraps were displayed at the Holocaust Museum in Washington. But Shurbaji was still inside.

“Fatigue spread on the pores of my face,” he wrote his fiancée during a brief respite in a prison that allowed letters. “I try to laugh but mixed with heartbreak, so I hold on to patience and to you.”

Two years later, a released detainee reported that Shurbaji had been beaten to death.

‘Don’t forget us’

In Syria, Lebanon, Turkey, Jordan, Germany, France, Sweden and beyond, families and survivors push on.

After he was freed in 2013, Ghabbash landed in Gaziantep, Turkey, where he runs women’s rights and aid programs for refugees in the last patch of rebel-held Syria.

Fakir, whose wife’s cooking has replenished his chubby cheeks, has joined a kind of alumni association for Saydnaya Prison survivors who help one another document their experiences, navigate trauma and find work.

Darwish struggles with insomnia and claustrophobia, but continues his work for accountability. He recently testified about Mezze prison in a French court hearing in the case of a Syrian-French father and son who died there — a university student and a teacher at a French school in Damascus. That helped French prosecutors secure arrest warrants for Mamlouk, the top security official, Hassan, the air force intelligence chief, and the head of Mezze prison. Now, Mamlouk could be arrested if he travels to Europe.

The threat of prosecution, Darwish said, is the only tool left to save detainees.

“It gives you energy, but it’s a heavy responsibility,” he said. “This could save a soul. Some are my friends. When I was released they said, ‘Please don’t forget us.’”

The New York Times