In his 1919 essay “Tradition and the Individual Talent,” T. S. Eliot wrote of the literary canon as an “order of monuments.” A lot of unwelcome monuments — of Robert E. Lee, Christopher Columbus, and others — have come down recently, but the de-platforming of literary eminences has been going on for some years now: Eliot himself, who once bestrode the Anglophone scene like some Colossus of Rhodes, now seems more like a crankily eloquent spokesman for imperial tradition.

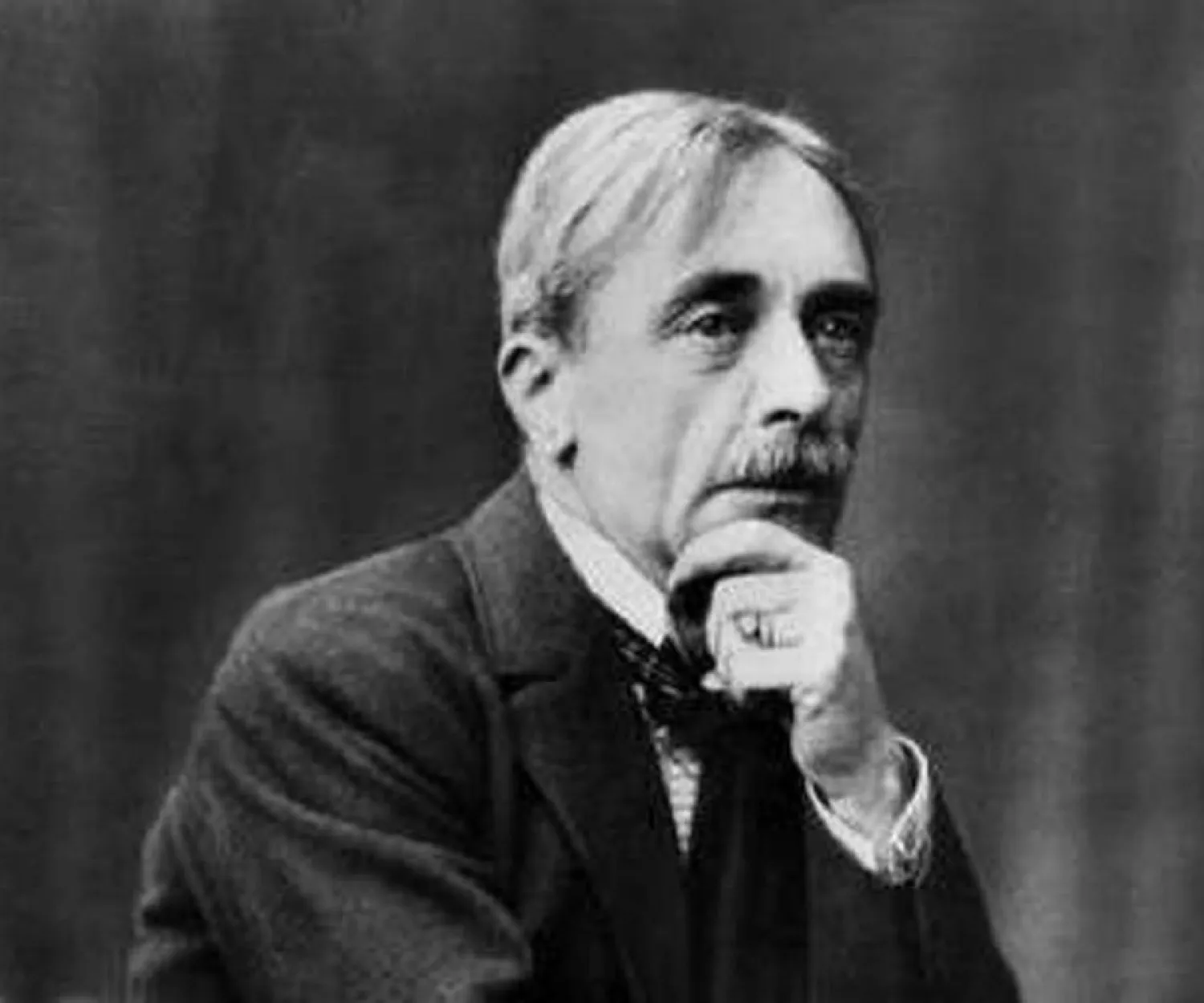

Paul Valéry (1871-1945) had the dubious fate of becoming a monument in his own lifetime, the personification of the quintessential “homme des lettres.” A member of the Académie française, he was France’s cultural representative to the League of Nations and an indefatigable lecturer and commentator. He held enough academic positions to overwhelm a half-dozen ordinary professors. He published over 20 books in various genres; his poetry, on which much of his reputation rests, is a very small share of the whole.

Valéry began as an acolyte of the Symbolist archbishop Stéphane Mallarmé, and an enthusiastic participant in the “decadent” movement — artificiality, hyperaestheticism — spearheaded by J. K. Huysmans. The poems of Album des vers anciens (published in 1920), written before an 1892 intellectual crisis led Valéry to renounce poetry for two decades, are dazzling and precise formal exercises, shot through with the trappings of the fin-de-siècle: classical personages (Helen, Venus, Orpheus, Narcissus) strike poses and declaim; languid female figures nod in static revery; and all too often one stumbles over “azure,” that poetically ubiquitous late-19th-century blue.

In 1912 André Gide and the publisher Gaston Gallimard pulled Valéry back into poetry, proposing to collect his early works. He began revising his poems of 20 years before and started what he thought would be a 40-line farewell to poetry. Four years later, it had become the 512 lines of La Jeune Parque (The Young Fate), his greatest poem and one of the recognized masterpieces of French literature.

Like Mallarmé’s Hérodiade and L’après-midi d’un faun, The Young Fate is an extended monologue, spoken by one of the fates, or Parcae. She is a girl on the cusp of adulthood, torn between memory and foreknowledge, awakening to the mysteries of sexual desire:

Dear rising ghosts, whose thirst is one with mine,

Desires, bright faces! … And you, sweet fruits of love,

Did the gods give me these maternal forms,

Sinuous curves and folds and chalices,

For life to embrace an altar of delights

Where the strange soul mingles with the eternal

Return, and seed and milk and blood still flow!

I am filled with the light of horror, foul harmony!

The poem’s movement is operatic, histrionic, as the Fate ranges across dreams, memory, and aspirations. She contemplates and rejects suicide; always, she is transfixed by the paradox of her existence: that this immortal soul, capable of the purest conceptions of perfection, is bound up with a mortal body, riven with passions and emotions.

Valéry never again achieved La Jeune Parque’s pitch of energy and tension, though “La Cimetière marin” (“The Cemetery by the Sea”), the central poem of Charmes (1922), attains perhaps a greater depth. His most famous poems are meditations on “big” questions: life and mortality, tradition, memory, yearning, our fleshly existence in relation to the spiritual perfection of which art seems to afford us a glimpse. A soliloquy by the serpent in Eden, “Sketch of a Serpent” (“Ébauche d’un Serpent”), which W. H. Auden admired for 25 years before deciding it was a “burlesque,” manages to distill most of John Milton’s theological argument — and much else — into its 250 lines. “O Vanity! First Cause!” the serpent says of God,

The one

Whose kingdom is in Heaven

Spoke with a voice that was the light

And lo, the universe spread wide.

As if his own pure pageantry

Went on too long, God broke the bar

Himself of his perfect eternity,

And became the One who dissipates

His Principle in consequences,

His Unity in stars.

If his “maître” Mallarmé was the high-priest of a magical cult, an alchemist of language, then Valéry aspired to be a chemist, a hard-nosed scientific explorer of words in combination. As early as 1889, Valéry described a “totally new and modern conception of the poet. He is no longer the disheveled madman who writes a whole poem in the course of one feverish night; he is a cool scientist, almost an algebraist, in the service of a subtle dreamer.” As Eliot put it in his essay “From Poe to Valéry,” “The tower of ivory has been fitted up as a laboratory.”

What’s paradoxical in this seemingly modern notion of the scientist-poet is the relentlessly conventional, even old-fashioned, themes that Valéry addresses — love, mortality, fate, destiny, beauty — and the world of modernity that he mostly eschews. A contemporary reader likely is struck by how trenchantly Valéry hews not merely to the traditional forms of French poetry, but to an elaborate, periphrastic vocabulary, a constant and sometimes bewildering metaphoricity. The sun in which the Fate walks is not the plain French “sol” but “the brilliant god” (“le dieu brillant”), the very thorns that tear her dress “the rebellious briar” (“la rebelle ronce”).

Nathaniel Rudavsky-Brody’s new selection of Valéry’s poems, The Idea of Perfection: The Poetry and Prose of Paul Valéry (2020, Farrar, Straus and Giroux), is welcome indeed. His translations are fresher than any previous English versions, certainly more idiomatically English than those of David Paul, the Princeton/Bollingen translator. Rudavsky-Brody has taken on a Herculean task. Not only does Valéry write in rhymed, metrically regular lines, but his verse constitutes (in the translator’s words) “a dense texture of assonance, internal rhyme, double meanings and shifting images, ‘resemblances’ that ‘flash from word to word’ many lines distant.”

Rudavsky-Brody can only suggest this texture, inherent to the sounds of the French words, in his English translations. Thankfully, he doesn’t attempt to precisely reproduce Valéry’s poetic forms. While his versions are in regular English meters — a decision, he explains, that has “as much to do with experiencing a similar set of formal constraints, of exercise, as characterized Valéry’s work, as with re-creating a semblance of their complex rhythms” — he mostly abstains from attempting Valéry’s rhymes (an Everest littered with the frozen corpses of previous translators).

The Idea of Perfection is an apt title, for Valéry was a perfectionist, endlessly tinkering with his poems. He’s famous for his pronouncement that a poem is never finished, only abandoned; his publisher practically had to tear the manuscript of La Jeune Parque out of his hands. “He was,” Eliot writes in his introduction to the 1958 collection The Art of Poetry, “the most self-conscious of all poets,” and in large part Valéry’s principal subject was the operations of his own sensibility. This is evident in his continual recourse to the figure of Narcissus, the young man entranced by his own reflection. In the prose poem “The Angel” (“L’Ange”), Valéry’s last work (though he had been revising it since 1921), the angel, staring at his reflection in the fountain, is unable to reconcile the vision of “a Man, in tears” with his own intellectual identity: “‘The pure being that I am,’ he said, ‘Intelligence that effortlessly absorbs all creation without being affected or altered by anything in return, will never recognize itself in this face brimming with sadness…’”

A notable inclusion in The Idea of Perfection — and what gives it the subtitle “poetry and prose” — is a series of chronological excerpts from Valéry’s “cahiers,” or notebooks. Valéry began writing his notebooks in 1894, and added to them every morning for the rest of his life. They cover the whole range of his polymathic interests — including poetry, philosophy, psychology, aesthetics, music, art, politics — and their 28,000 pages have never been properly edited; the two fat volumes of Cahiers in the prestigious Pléiade edition (1973-74) contain only about 10 percent of the whole.

Rudavsky-Brody’s 57 pages of extracts are probably the first most English-language readers have seen of the notebooks. The ruminations on psychology and longing, the philosophical musings, will be familiar to readers of Valéry’s essays. But some interesting passages show the poet as a keen observer of the details of natural, and urban, reality. These give us a glimpse of a very different scientist-poet: the American William Carlos Williams, who would compare his own practice (in the long poem Paterson) to that of Marie Curie, distilling visible reality into its radiant gists as Curie obtained radium from pitchblende.

The Young Fate and “The Cemetery by the Sea” remain monumental, deeply impressive works. Yet Valéry’s formal neoclassicism feels far more distant to a contemporary reader than the work of his younger colleagues. André Breton, Blaise Cendrars, and even Guillaume Apollinaire (who died in 1918) seem far more modern, more attuned to a world of rapid transit and mass communications. It would be a mistake, however, to relegate Valéry to the graveyard of discarded statuary. The beauty and power of his best writing is undeniable, and the human dilemmas his work addresses — mortality, embodiment, the longing for perfection — remain with us.

(Hyper Allergic)