Power shortages and soaring petrol prices mean many Lebanese university students can neither afford to reach their classes nor study from home, a conundrum that is ravaging a generation's future.

Agnes, a 22-year-old dentistry student from south Lebanon, is among the few still plodding to class in Beirut four days a week.

The five hours she spends on a bus daily now costs her 1.3 million Lebanese pounds a month -- "that's half of my father's salary", she said.

Such expenses are now beyond the reach of most Lebanese students, with their country in the throes of a financial, political and health crisis that has ravaged its economy.

The national currency has lost more than 95 percent of its value on the black market, and the minimum wage of 675,000 pounds is worth little more than $20, which barely pays for a full tank of petrol.

Transport "is becoming more expensive than my semester's tuition fees", according to AFP, Tarek, a 25-year-old student at the Islamic University of Lebanon who, like the others interviewed, declined to give a family name.

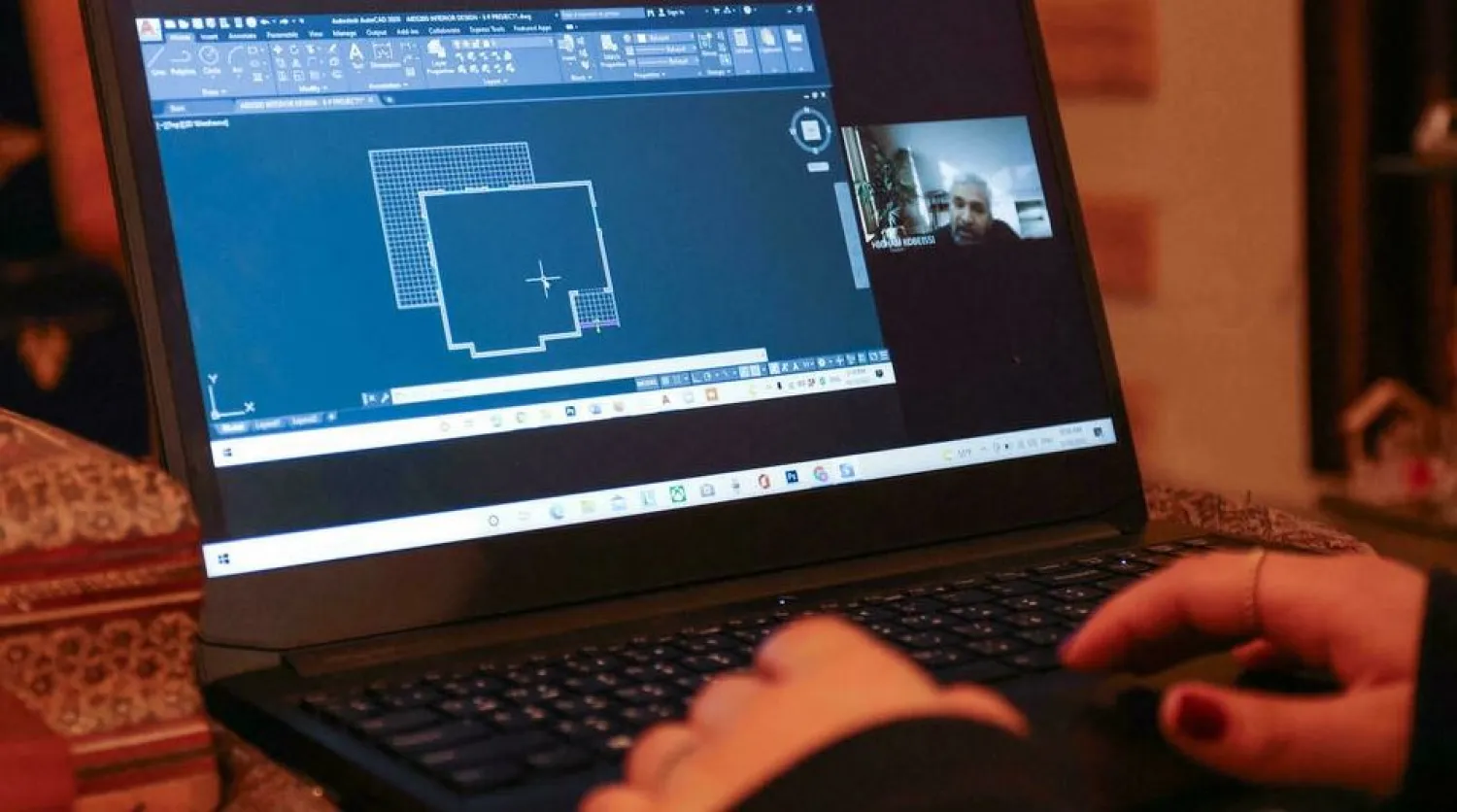

As a result, and also because teachers face similar difficulties, many universities continue to offer online classes.

But staying connected during state power cuts that often last more than 20 hours a day also comes at a cost.

Amina, 22, a student at the public Lebanese University, said she has reverted to doing most of her work from books due to the lack of electricity at home.

There are "about 75 students in the class, of whom a maximum of five" can attend online, she said, adding that she needed to study around nine hours a day in order not to fall behind.

To keep laptops and modems running, families have to pay for expensive private generators, but that option too is unaffordable for many.

Some students are spending their money on mobile phone data so they can connect their computers to an internet hotspot.

The spaghetti wiring connecting laptops, routers and phone chargers to all manner of back-up devices -- from commercial uninterruptible power supplies to homemade contraptions using car batteries -- means study areas now often look like the back of an IT workshop.

"All of this is additional cost," said 22-year-old Ghassan, a student at the Sagesse University.

Several institutions have set up special student funds in an attempt to maintain enrolment levels, said Jean-Noel Baleo, Middle East director of the Francophone University Agency -- a network of French-speaking institutions.

"Some universities are keeping students who cannot pay, which is a form of hidden bursary," he told AFP.

But he said such Band-Aid fixes were barely slowing the decline of a higher education system that was once a source of national pride, and whose multilingual graduates flooded the region's elites.

"It's a collapse we're talking about, and there's more bad news on the way," said Baleo, who predicted the definitive closure of some universities and an intensifying brain drain.

Education Minister Abbas Halabi admitted he was largely powerless to stem the sector's crisis.

"I tried to secure subsidies for the Lebanese University from foreign donors but at this stage they have not replied positively," he told AFP.

"The Lebanese state does not have the means."

Even as the financial meltdown threatens several pillars of the country's education system, Lebanon's political elite -- widely blamed for collapse -- have resisted reforms that would open the way for international assistance, and the cabinet has not met in three months.

"Today, the easiest option is to set up online classes, even if that remains a difficult option. Rising transport costs make it the least-worst fix," Baleo said.

In the meantime, students like Tarek say the crisis is turning university life into an ordeal.

"It's exhausting and depressing," he said.

"I am considering quitting university... The wages are so bad that you're not even motivated to graduate to find a job," he said.

Student Ghassan said he only wanted to graduate so it could help him leave the country.

"All the youth want to leave because there's no clear future here," he said.