Hermes headlined Saturday’s installment of Paris Fashion Week with a cinematic, surrealist runway staging, but the lack of celebrities attending and the patchy drizzle put a slight dampener on the usually high-octane events.

Like Milan before it, Paris is undertaking an unusual fashion season for Spring-Summer 2021 because of the coronavirus pandemic. The nine-day calendar is flitting between 16 ready-to-wear runway collections with masked guests in seated rows, 20 in-person presentations and several dozen completely digital shows streamed online with promotional videos.

Some of Saturday's highlights:

Hermes

Prints of Greco-Roman goddess sculptures adorned columns marking out Hermes' labyrinthine show, while mirrors around the set reflected parts of their marble limbs. The creative presentation referenced surrealists Salvador Dali and Jean Cocteau, evoking a sense of magic, mystery and depth.

Depth was indeed the key theme for minimalist designer Nadège Vanhee-Cybulski, but the magic and mystery were sometimes missing in the clothes. Shimmering metallic mesh came as an outer layer on pared-down undergarments in dark and muted hues.

In one LWD (Little White Dress), the gold meshing resembled kinky chainmail and felt very 1990s. Elsewhere, the play on depth continued as the sides were scooped out of an ethnic-looking brown dress to expose the model's skin.

It was, on the whole, a low-energy collection. Still, individual garments were high in sophistication, especially those with layered paneling. One coat in old rose had a chic rolled-up collar that riffed on aviation attire.

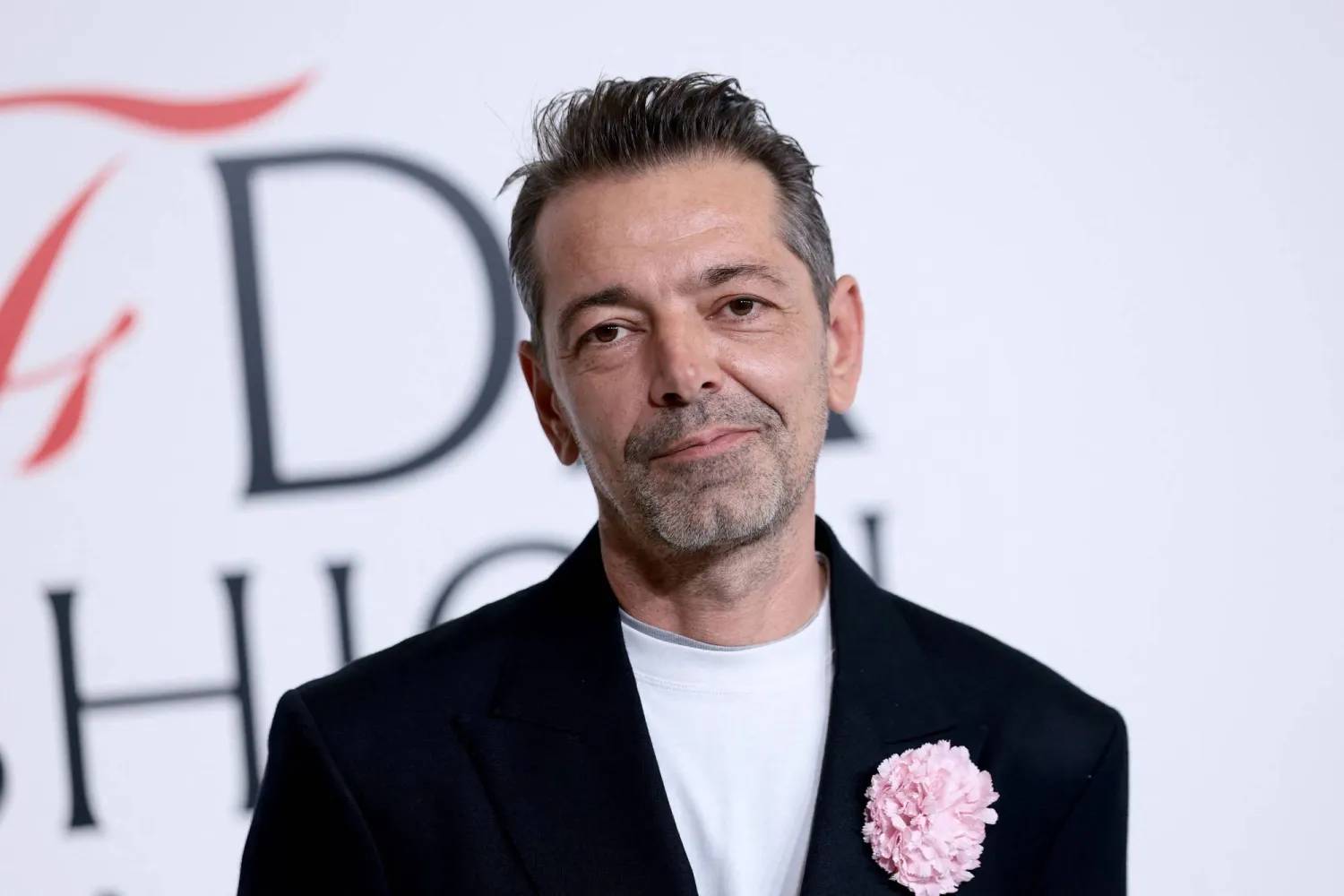

Altuzarra is sophisticated

Tailoring, ruching, draping and layering were the winning formula for Paris-born designer Joseph Altuzarra in his refined-looking Spring-Summer fare. A Chinese white tunic-gown that was loose and open-necked had an angelic quality. Delicacy was in evidence in the minimalist black cord that tied the garment's waist.

A gathered gown in camouflage green had sweeping panels of gathered fabric at the skirt that evoked a goddess in the wind. It was, the house said following the show, inspired by the windswept sci-fi movie “Dune.”

The best looks were also ones in which the designer, who has a Chinese, American and French background, mixed up cultural references. A silver Western trench coat was fashioned in voluminous proportions and layers, and its lower part had the feel of a Samurai hakama (skirt-like pants) with an Obi belt.

Altuzarra has shown versatility in his over ten years of collections that have switched from the bright and joyful, to more refined and couture-infused, designs. On Saturday, it was a mixture of both.

Ester Manas loves everyone

Ester Manas is a brand that has been making ripples at Paris Fashion Week in recent seasons with a body positive approach that is, sadly, all too rare. The design duo at the helm -- French-born Ester Manas and Belgian-born Balthazar Delepierre -- said that their Saturday presentation “has been inspired by real women, regardless of their sizes, colors or shapes.”

The show, entitled “Superhuman,” featured relaxed looks with loose proportions and flashes of design fun. A plus-sized model rocked a vermilion red knit dress with cleavage, split leg and peekaboo holes at a midriff adorned with a large heart. Plus-size is sexy and we love it: The loud and clear message was delivered.

There was also some design flair, such as a loose marigold yellow pantsuit with a gargantuan fun peplum. Wearable was this season’s priority.