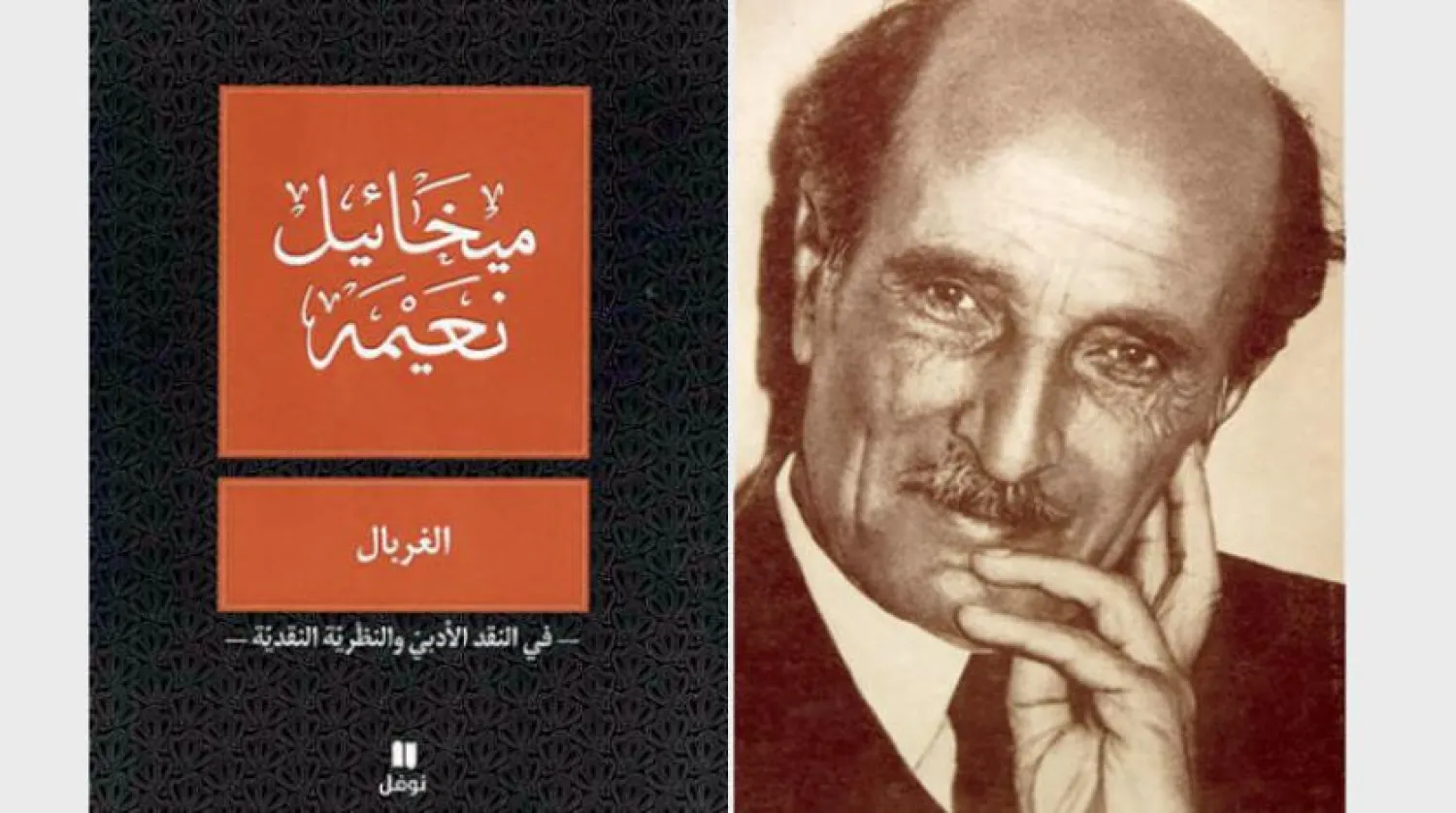

Did the "Al-Ghirbal" book age? Did it lose its impact? Did it become obsolete? Yes, maybe in some of its aspects, but not in its essence.

The spirit of the book is still alive and reviving. It is still relevant to our current reality. In a nutshell, when we read the book, we feel that Mikhail Naimy is still living with us, and this is the loudest proof on his value and prominence as an Arabic, progressive, pioneering intellectual.

The book includes a large chapter, the "The Croaking of Frogs: Position of Language in Literature" that is enough to immortalize the book itself and Naimy.

But what does it mean?

It means the frogs of literature paralyze us with their croaks, swamps, and slackness. They paralyze the development of the Arabic language and Arabic life itself. They keep correcting your language: "say this and don’t say that", "this is acceptable and this is forbidden", "this is correct according to Al-Tha'alibi and Al-Asmai, and that is not, be careful", and "don’t you dare to violate the liturgies of inherited language, the Arabic language should remain s it is, as it has been for centuries."

Why don't you write in the correct dictionary language? Otherwise, you would violate literary standards. Let us take Gibran Khalil Gibran's famed "Al-Mawakeb" poem, which was sung by by Fairuz, in which he wrote:

"Have you bathed in its fragrance and dried yourself in its light."

This great poem reminds us of Lebanon’s mountains, creeks, and valleys where you can feel the scent of existence. But the problem in this etherical poem is that it contains a linguistic mistake! The literary frogs or the Arabic language frogs describe it as linguistic mistake, frown upon it, and blame the writer for it.

For them, Gibran committed an unforgivable crime against the Arabic language. But what’s this crime? Where is it? I can’t see it. Why did the poet use the word "Yatahamam" (Arabic for bathe) instead of its legitimate, classic Arabic alternative "istaham"? Can a genius, creative writer commit to the literary language of Al-Tha'alibi and Al-Asmai? Wouldn’t this commitment affect his genius and creativity?

The poet has the right to invent new words, to ignite the language, to practice his freedom.

Without this freedom, there would be no linguistic development, and Arabic literature would die if we listened to the croaking frogs. Instead, we should listen carefully to Naimy, who said: "If the Arabic language frogs saw the history of their language, they would find the greatest proof on this saying. Didn’t they see that the language we use today to write in our magazines and newspapers and to speak on stages is different from the language of Mudar, Tamim, Humair, and Quraysh? Didn’t they notice that if their ancestors managed to control us 2,000 years ago, we wouldn’t have the language we use today?"

Here lies the importance of this great book. It really cares about the Arabic language and seeks to develop and save it, but how? By allowing it to inspire its terms from our life. However, the close-minded linguists want to control and suffocate the language. For example, the French people envy us because they don’t have a feminine form for the word "doctor" and have to use "female doctor"; they don’t have a feminine form for the word "writer" as well, but we do. In fact, they have recently invented a feminine form of the world writer, but it’s ugly. And yet, some Arab writers still find new ways to bring more complexity to our language.

But why all this burden? Let the Arabic language breathe, let it loosen, let it become closer to our daily life language.