Final episode

Leila Khaled is approaching 80. She has spent her life chasing a dream that has not been achieved. She has not abandoned it and feels no regret or remorse. She joined the Arab Nationalist Movement while she was still in high school and later joined the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP).

She rose up the ranks to become a member of its leading body. Danger would become her daily companion when she joined the PFLP’s External Operations headed by Wadie Haddad.

Throughout the years, I had always wondered whether there was any connection between the External Operations and the intelligence empire of the Soviets’ KGB that was long headed by Yuri Andropov before he became master of the Kremlin.

Khaled had the answer. She said: “Wadie opened the channel of communication with the Soviets through a military attaché in Beirut. At one point, we were building bombs that could breach the entrance of airport gates, no matter how high advanced they were.”

“We tested some of them, leaving the British with quite a surprise,” she recalled in an interview to Asharq Al-Awsat in Amman. “One day we realized that we needed a specific spring to develop the bomb. We didn’t trust any embassy and we used to resolve our problems through Wadie’s doctor friends at the American University of Beirut hospital. This time, they couldn’t find a solution to our problem.”

“It was difficult for us to approach the Soviet embassy or arrange a meeting elsewhere. Western security agencies were tracking us. The best way to meet the Soviet military attaché was at the seaside promenade where we could appear as casual pedestrians.”

“We explained our case to the official, who relayed our request to his command. Afterwards, we headed to Moscow and received what we had asked for. I did not take part in the meetings, but did go with Wadie to Moscow,” Khaled said.

I asked her about a meeting that had allegedly taken place between Haddad and Andropov in a forest outside of Moscow. She replied that she had not taken part in that meeting.

PLO member Leila Khaled and a group of Palestinian women attend the 16th Palestinian National Council meeting in Algiers. (Getty)

Forest meeting

The forest meeting did indeed happen. Haddad was hosted at a palace in the middle of a forest. He held a series of meetings with Soviet officials that tackled military, political and technical issues. The talks were capped with a meeting with KGB leader Andropov.

The topic at hand was not easy. At the time it was called “terrorism”. The discussions quickly revealed evident differences over the two-state solution. Haddad stressed that “our country is one and indivisible. We have never thought about the rise of two states. If the whole of Palestine, including Jerusalem, but excluding Haifa, were to be offered to us, we would turn it down.”

He was then asked if he had any specific demands. Haddad replied: “I had made a list before my arrival. I am not greedy, but in need. We need the list to be met in full or not at all.” He handed over his list and indeed, the Soviets fulfilled all of his demands. Some weapons, machineguns, rifles, ammunition, timers, and certain devices.

Khaled recalled: “After some time, we were contacted in Aden. Some six kilometers off the shore, we received all the weapons that Wadie had asked for. There would be no follow up to the meeting in the forest. The relations would remain as they were. Later, at Wadie’s funeral, a Soviet diplomat asked us who would be his successor and we told him that now was not the time for such discussions. Actual relations were never established after that.”

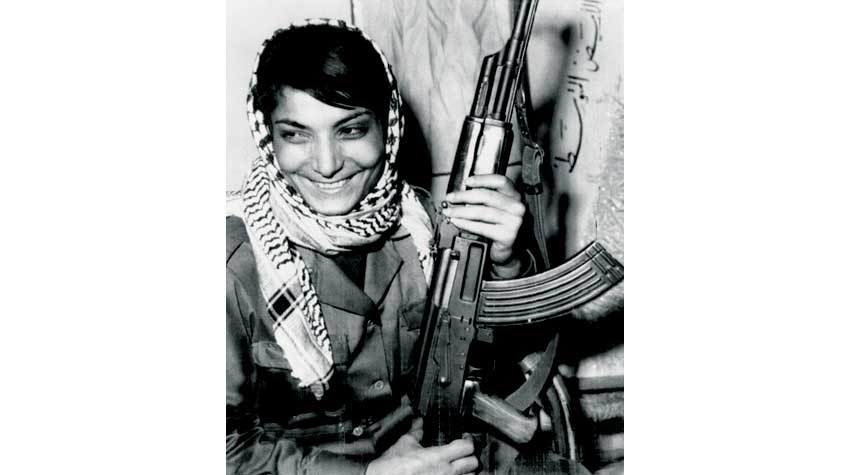

Leila Khaled smiles after returning to Jordan following the hijacking of after American T.W.A. jetliner in Damascus (Getty)

Plane hijacker

I was a student in the southern Lebanese city of Sidon when news broke out that a young Palestinian woman, who called herself Shadia Abou Ghazaleh, had hijacked an Israeli plane and flown it over Haifa before landing in Damascus airport. Abou Ghazaleh was the name of the PFLP’s first female operative to be killed.

The news of the hijacking was exceptionally exciting. It was uncommon in the Middle East and even the world for a woman to hijack a plane. Her family had been displaced to Lebanon in 1948. She graduated from a school in Sidon before joining the PFLP and later the External Operations.

I had never imagined back then that decades later, I would one day be in an apartment in Amman to listen to Khaled recount to Asharq Al-Awsat what happened at that time.

Haddad was studying medicine at the American University of Beirut. His colleague, George Habash, dreamed of returning to Palestine. He was horrified at the thought of a world that would get used to seeing Palestinians living under occupation or displaced in camps in Jordan, Syria and Lebanon. He was aware of Israel’s power and strength of its ties with the West. He feared that Palestine would be forgotten by the world.

He thought of different ways to again draw the world’s attention to the plight of the Palestinian people. And so, the idea of hijacking planes was born. It would serve as a reminder to the world and to prompt the release of prisoners held in Israeli jails.

Khaled stressed that Haddad was aware of how sensitive this issue was to international public opinion. That is why he stressed that the hijackers should never harm passengers or fire back at any shooter.

Two incidents would precede Khaled’s first hijacking. The first was the hijacking of the Algeria-bound Israeli El Al flight by Youssef Rajab and Abou Hassan Ghosh. “Since negotiations only took place between nations, their operation ended in pledges,” recalled Khaled. The second was an attack on an Israeli plane before takeoff from Zurich airport. The operation was carried out by four people, including Amina Dahbour. The attackers turned themselves over the police, but one guard on the plane managed to exit the aircraft and shoot dead one of the perpetrators, Abdul Mohsen Hassan.

Plane hijacking and the ‘hefty catch’

It was the summer of 1969. Khaled was happy and excited. She was chosen to carry out a shocking and unprecedented operation – evidence of the faith she enjoyed from the leadership that recognized her loyalty and abilities. She received training at the hands of PFLP member Salim Issawi in Jordan. He would also be her partner during the hijacking.

Haddad briefed them on the plan: Hijack a TWA flight flying from Los Angeles to Tel Aviv. The purpose was to exchange Palestinian prisoners with the Israeli passengers. Reportedly, a major Israeli figure was supposed to be on board the flight, which would have forced Israel to agree to negotiate. Khaled tried to find out who that important person was from Haddad, but he said that it was a “need to know” situation. She would later find out that it was General Yitzhak Rabin, who would later become prime minister. He would ultimately change his itinerary and deprive the hijackers of a “hefty catch”.

Khaled would undergo intense training for four months. She would learn about how planes work and about maps and coordinates and what to do if the aircraft encountered turbulence. The American flight had two stops in Europe, Rome and Athens, before arriving in Tel Aviv. Khaled and Issawi departed Beirut to Rome and booked a flight to Athens.

August 29, 1969, was the day it happened. Khaled sat in first class with Issawi. The plan would go into action a half hour into the flight when the plane was at 35,000 feet. They took out their weapons and asked the first class passengers to head to the tourist class. Issawi and Khaled then stormed the cockpit.

She told the pilot: “I am Captain Shadia Abou Ghazaleh of the Che Guevara unit in the PFLP.” She informed him that she would take command. She took his headset and microphone. He noticed that she had taken off the pin of a hand grenade she was carrying and asked that she rest her hand so that the explosive would not go off.

“I explained to the pilot and the copilot that we were not here to kill or blow up anyone. We only want our rightful demands,” she added. “I asked that the plane’s code be changed to Popular Front Liberated Arab Palestine. I told them that we will not respond to any call that does not use that code. I asked the pilot to head directly to Tel Aviv without stopping in Athens.”

She added: “We didn’t want to land in Tel Aviv. We only wanted to fly over the Palestinian territories to remind the world of our cause.” She told the pilot that they wanted to fly to Syria. “I heard an exchange between the Damascus and Beirut watch towers. The Syrians asked: ‘Where is this plane going?’ The Lebanese replied: ‘Not to us. It’s headed to you.’”

Damascus airport was still new and not operating at full capacity. This was the first American flight to land there. Haddad had not informed the Syrian authorities of his plan ahead of time because he did not trust them.

“The plane landed in Damascus according to plan. We turned ourselves over to the authorities and explained to them why we did what we did,” said Khaled.

The passengers, some 122 of them, ran towards the airport building. Only a small group ran towards the fence. “I told the police that they may be Israelis and indeed, they were,” recalled Khaled.

“A Syrian officer asked us: ‘Why did you come to us?’ Shocked, I replied: ‘I came to Syria, not to Israel.’ He was angered by this, but the operation had still gone according to plan,” she said. The ensuing negotiations led to the release of 23 Palestinian and Arab prisoners and two Syrian pilots, who were detained during the 1867 war.

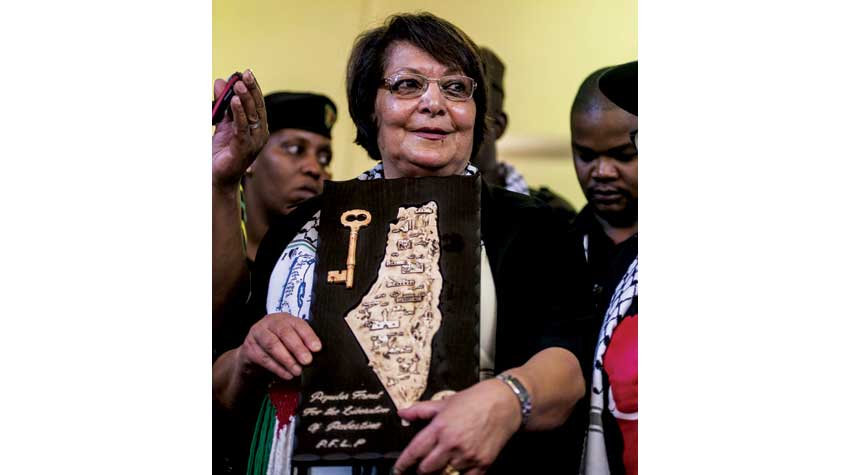

Leila Khaled is seen holding up a map of Palestine after addressing the crowd at the DOCC Hall in Orlando East, Soweto, South Africa in 2015 (Getty)

‘Salem’, ‘Mariam’ and ‘Mujahed’

The popularity of the PFLP and Haddad would skyrocket after the first hijackings. Anti-West groups and individuals seeking an opportunity to tangle with their perceived enemy soon poured into the Middle East. The PFLP’s External Operations would later become tied to a group of people from diverse nationalities. Jordan was their preferred destination because the Palestinian factions had set up base there while the Jordanian army did little to stop them because it wanted to avert a clash that would eventually happen later.

The relations between these groups would start off with reaching common political ground. Once firmly established, they would begin to cooperate according to a specific agenda. They would exchange information, documents and weapons. They would also provide facilitations and trainings and sometimes take part in direct operations.

The West named the network that was established by Haddad the “empire of terrorism” because of the many foreigners who were involved. The External Operations would become a hub and training and planning ground that would produce figures that shocked the world with their violence: Venezuela’s “Salem”, who was none other than the infamous Carlos, “Mariam”, who was Fusako Shigenobu, head of the Japanese Red Army, and “Mujahid”, who was Hagop Hagopian, head of the Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia.

After his death, Haddad’s “students” would eventually be tracked down. Some would be shot dead and others would land in jail. Perhaps their downfall could be blamed on their poor organization and lack of uniting leadership. Perhaps they committed the error of forming ties with countries and agencies. Of course, infamy could be lethal in a world that must be shrouded in secrecy.

In 1970, Jordan was at boiling point. Coexistence between the army and Palestinian factions had grown fragile and strained. Coexistence between two authorities in the same country is unwieldly at best. Ceasefires acted more as sedatives in the buildup to zero hour when one party had to give.

In July 1970, the Israeli Mossad tried to assassinate Haddad in Beirut. They attacked his bedroom, but he was in another room where he was deep in conversation with Khaled. Both came out alive. These discussions would move to the American University of Beirut hospital where Haddad’s wife was treating their son, Hani.

At the hospital, Khaled would study a book on flight movements all over the world. She searched for El Al and noted the pattern of flights to and from Tel Aviv. She said she proposed to Haddad carrying out a new hijacking in retaliation to the attempt on his life. He agreed and asked her to follow up on it and bring in female comrades to train.

The day of plane hijackings

Haddad would send Khaled to a dinner with people she did not know. One of the guests told her he had just returned from a hunting trip in Jordan where he came across a facility, similar to an airport, that the British had used for their trainings. She eagerly listened and asked more about the location to determine if it was suitable for her plan.

Khaled said she vividly remembers that night. “I was eager for the dinner to be over so I could go back to Haddad and tell him all about what I had learned. It was decided that I would go scout the location. I was accompanied by a comrade from the Arab Nationalist Movement. At the facility, I ran around to test the firmness of the ground. My comrade asked me why I was so interested and I replied that I was looking for an appropriate training ground.”

The plan called for hijacking three planes at once and flying them to what was called the “revolutionary airport” - the Jordanian site. “Negotiations would then be held over the liberation of prisoners held in enemy and European jails,” Khaled said.

September 6, 1970, would become known as the day of plane hijackings in the world. All eyes turned to the “revolutionary airport”. The attempt to hijack an El Al flight was thwarted while it was in the air. Two planes, one Swiss and one American, were blown up at the airport. Another American plane was blown up at Cairo airport.

Luck was not on Khaled’s side this time. Four of her accomplices were supposed to board the El Al flight in Amsterdam, but two failed to secure a reservation. She boarded the plane with her accomplice, Patrick Argüello. The hijacking failed and the plane landed in London. Argüello was killed by a marshal that was on the plane and Khaled threw a hand grenade that did not explode. She was arrested in Britain. After an investigation and weeks of detention, authorities were forced to release her as part of an exchange.

Mossad under the bed

I asked her if the Mossad had ever managed to reach her. She replied: “Yes, in Beirut. They planted an explosive under my bed. Security measures at the time demanded that we change our apartments constantly. I was training women in the South and the Bekaa. I would return exhausted to my temporary furnished apartment in the capital. I would immediately collapse in bed and get as much rest as possible because Wadie would often send for me and he believed that we had no right to feel tired.”

That day, Khaled returned to her apartment in Beirut’s Caracas neighborhood and by chance, she noticed a black box under her bed. “I wasn’t sure if that box was mine. I had my doubts. I immediately went to the PFLP office. A explosives expert head to the apartment and discovered that the box held ten kilograms of explosives.”