On April 8, 2024, a total solar eclipse traversed a wide swathe of North America stretching 2,500 miles (4,000 km) from Mexico's Pacific Coast through Texas and across 14 other US states into Canada. The period of totality, when the moon covered the face of the sun, lasted about four minutes depending on the location.

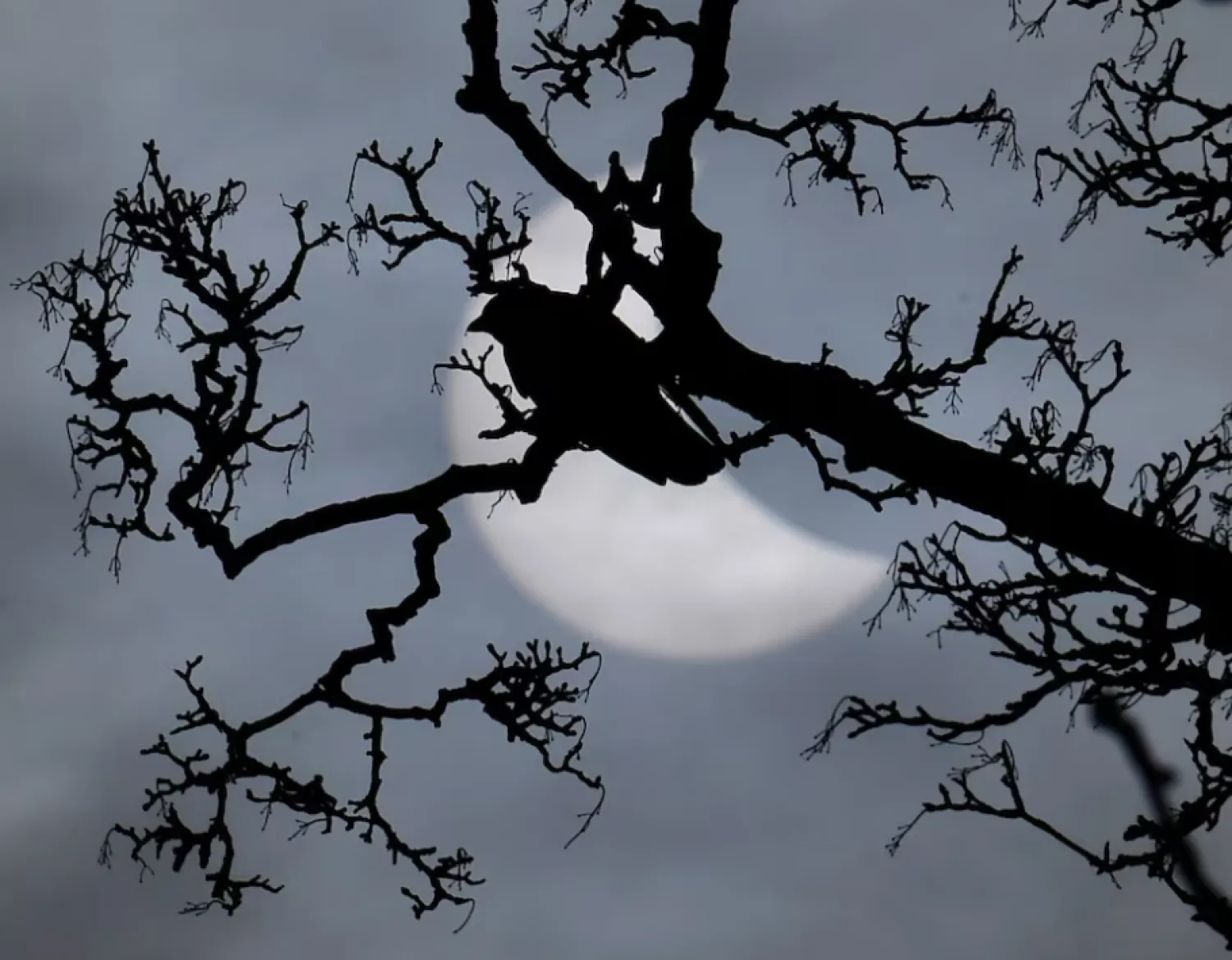

While throngs of people gazed skyward to see the celestial show, scientists were studying the effects of the eclipse on birds, whose daily and seasonal rhythms are strongly guided by sunlight. They documented changes in vocal behavior in most - not all - species studied, with birds that naturally make a burst of songs and calls around daybreak the most affected, Reuters reported.

When the sunlight began to return after totality, some species produced their customary "dawn chorus," as if greeting a new day. Some species fell silent, while others did not change their behavior compared to a normal day.

"Light is one of the most powerful forces shaping bird behavior, and even a four-minute 'night' was enough for many species to act as if it were morning again. That tells us just how sensitive some birds are to changes in light," said Liz Aguilar, a doctoral student in evolution, ecology and behavior at Indiana University and lead author of the study published this week in the journal Science.

"Based on previous research, most of which was collected in the lab, we know that changes in light are the most important cues used by living organisms to time their daily rhythms. As day transitions to night and vice versa, hormone levels and gene expression in the body change, and that causes differences in behavior," said study co-author Dustin Reichard, a biology professor at Ohio Wesleyan University.

While there had been anecdotal evidence concerning the behavior of birds during an eclipse and some research involving certain species, this study offered the most comprehensive look yet at the subject, with the findings coming from two datasets.

Fourteen recording units placed around Bloomington, Indiana, captured more than 100,000 bird vocalizations that were analyzed using machine-learning tools to discern the individual species making the songs and calls. In addition, nearly 1,700 people across North America submitted more than 11,000 observations of bird behavior around the eclipse through an app created by the researchers called SolarBird that let anyone in the general public with a smartphone contribute data.

A total of 52 species were documented around Bloomington, 29 of which exhibited significant changes in their vocal behavior as the eclipse occurred compared to a normal April afternoon.

"Different bird species greet the dawn in very different ways. Some have loud, elaborate dawn choruses, while others are much quieter. We found that species known for the most intense dawn choruses were also the ones most likely to react to the eclipse," Aguilar said.

Various species behaved in various ways. For instance, American robins, known for singing very early in the morning while it is still dark, had one of the largest increases in vocalizations during and just after totality - six times higher than a non-eclipse afternoon.

Barred owls vocalized four times as much as a non-eclipse afternoon just after totality ended, when light levels resembled the dawn or dusk periods when their activity normally increases.

Carolina wrens, also known for being particularly vocal including around dawn, were not affected at all by the eclipse.

"It actually makes sense that not all species reacted the same way. Birds differ in how sensitive they are to changes in light. It would have been more surprising if every species responded identically. Each species has its own activity patterns, energetic needs and sensory abilities, so they interpret environmental changes differently," Aguilar said.

"We looked for patterns among closely related species and also compared migratory versus resident birds, but we didn't find any consistent differences," Aguilar said. "That tells us there's still more to learn about what makes certain species more or less sensitive to sudden changes in light, which will be an important direction for future research."