Thirty years ago today, Liamine Zeroual won Algeria’s 1995 presidential election, an event that marked a turning point in a nation ravaged by violence since the cancellation of the 1991 vote won by the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS). Until then, critics of the army-backed authorities had repeatedly accused the regime of lacking “popular legitimacy.”

Zeroual’s decision to seek a mandate at the ballot box abruptly deprived the opposition of that argument. It was, in every sense, a political gamble: the country was drowning in bloodshed, armed groups were at their peak, and they openly threatened anyone who dared approach a polling station. Major opposition parties - FIS, the National Liberation Front (FLN) and the Socialist Forces Front (FFS) - all called for a boycott.

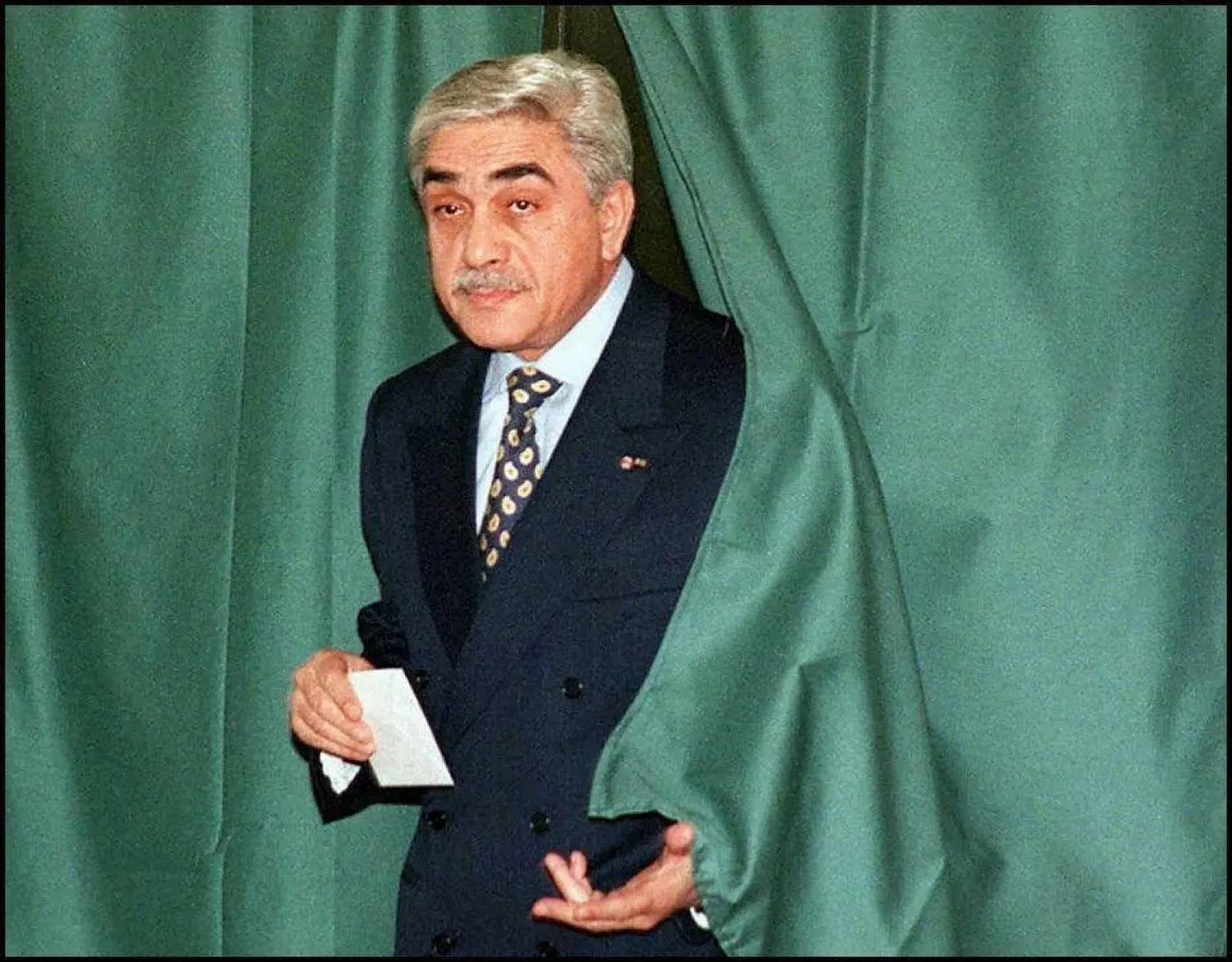

Zeroual pressed ahead. His victory was not unexpected; he was the interim president, a former defense minister and enjoyed firm military backing. The surprise lay in the manner of his win. Voters lined up at polling centers despite the danger, shattering the barrier of fear that terrorism had imposed.

For the authorities, Zeroual’s triumph restored long-contested “legitimacy” and effectively signaled the beginning of the end of Algeria’s “black decade.” The following year he held parliamentary elections that formally closed the chapter of FIS’s 1991 win. Meanwhile, the balance of the conflict shifted decisively toward the army, which dealt severe blows to armed groups and compelled many militants to surrender under an amnesty later implemented by Zeroual’s successor, Abdelaziz Bouteflika, in 1999.

Most young Algerians, with little memory of the 1990s carnage, may not grasp the significance of Zeroual’s victory. To mark the anniversary, Asharq Al-Awsat examines declassified British government files held in the UK National Archives, shedding light on Western reactions to the 1995 vote.

The documents reveal confusion and caution in Western capitals. France, for instance, refrained from issuing a formal “congratulation,” while Britain’s Foreign Office deemed it inappropriate for Queen Elizabeth II to send her own message, although the prime minister would do so.

A report dated 17 November 1995 from Britain’s ambassador to Algiers, Peter Marshall, notes that Zeroual secured a “landslide victory,” winning 61.34 percent of the vote. He wrote that the election “defied three years of terrorism and repression” as well as threats of disruption by the banned FIS and armed Islamist groups. Turnout reached a surprising 75 percent of the 16 million registered voters, well above official expectations.

According to the report, analysts viewed the result as “a strong mandate against violence rather than an endorsement of any particular candidate.” High participation, especially among women and young people, sent the authorities a clear message that “the large silent majority wants to live in peace in a secular state.”

The documents highlight voters’ rejection of Zeroual’s main rival, the moderate Islamist Mahfoud Nahnah, who won 25.38 percent of the vote, less than 20 percent of the electorate. This signaled “a firm refusal of Islamic rule,” according to the report. Meanwhile, the boycott strategy of major opposition parties “misread the public mood,” and may even have strengthened the regime’s hand. The report concluded that legitimacy conferred by the election was “more solid than expected,” prompting even boycotting groups, including FIS and the FLN, to issue conciliatory statements.

The success of the vote, the British embassy observed, was enabled by unprecedented security measures. Massive military and police deployment produced what was described as one of Algeria’s most peaceful days in years. Although some alleged fraud, British officials believed the process was conducted “with integrity and transparency,” and the figures were “reasonably accurate.”

Yet the documents also warned that Algeria remained under the same military-backed leadership. The regime had achieved its goal of acquiring “a degree of democratic legitimacy,” allowing the generals to “step back from the spotlight.” But doubts persisted over whether Zeroual would have any greater freedom of action, with his name continuing to serve as “a shorthand for the system itself.” Analysts cautioned that the danger was that the authorities might interpret the result more as “approval of their previous policies than as a demand for change.”

Looking ahead, the files expected Zeroual to pursue his dual strategy of political dialogue and counter-terrorism, “with a slight tilt toward the latter.” His promise of parliamentary elections the following year could entice opposition groups to re-engage, though reintegrating the banned FIS seemed increasingly remote. The report stressed that long-term stability remained uncertain: the deep social and economic grievances that fueled extremism were still “as intractable as ever,” and armed groups were unlikely to simply abandon their struggle.

The documents show that international reactions were “satisfied but cautious.” The European Union welcomed the peaceful vote and high participation, hoping to tie political progress to sustainable economic reforms. France issued a “muted” response; although President Jacques Chirac would send a message, it would avoid explicit congratulations. Privately, Paris was pleased, believing high turnout had weakened both FIS and the FFS, and awaited early signals of Zeroual’s commitment to legislative elections.

Other European leaders, including those of Germany, Russia, Greece and Spain, also sent messages. The British prime minister would congratulate Zeroual while noting London’s interest in political dialogue and commercial opportunities, including BP’s multibillion-dollar bid in Algeria. A royal message, however, remained “inappropriate,” given the military regime’s record of brutality.