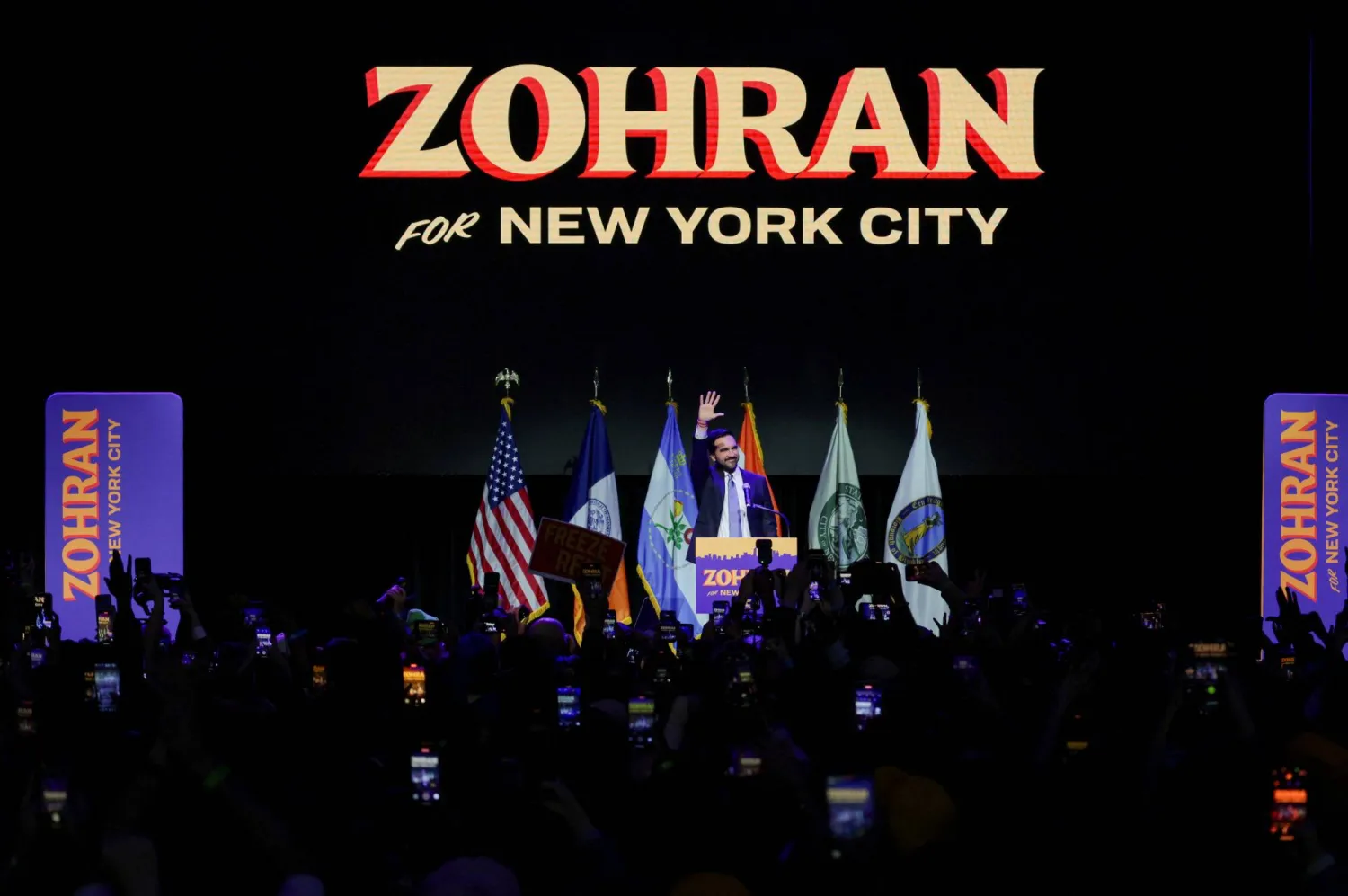

When he announced his run for mayor last October, Zohran Mamdani was a state lawmaker unknown to most New York City residents.

But that was before the 34-year-old democratic socialist crashed the national political scene with a stunning upset over former New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo in June’s Democratic primary.

On Tuesday, Mamdani completed his political ascension, again vanquishing Cuomo, as well as Republican candidate Curtis Sliwa, in the general election.

The former foreclosure prevention counselor and one-time rapper becomes the city’s first Muslim mayor, first born in Africa, and first of South Asian heritage — not to mention its youngest mayor in more than a century.

“I will wake up each morning with a singular purpose: To make this city better for you than it was the day before,” Mamdani promised New Yorkers in his victory speech.

Here’s a look at the next chief executive of America’s largest city:

Mamdani's progressive promises for New York City

Mamdani ran on an optimistic vision for New York City.

His campaign was packed with big policies aimed at lowering the cost of living for everyday New Yorkers, from free child care, free buses to a rent freeze for people living in rent-regulated apartments and new affordable housing — much of it funded by raising taxes on the wealthy.

He’s also proposed launching a pilot program for city-run grocery stores as a way to combat high food prices.

Since his Democratic primary win, Mamdani has moderated some of his more polarizing rhetoric, particularly around law enforcement.

He backed off a 2020 post calling to “defund” the New York Police Department and publicly apologized to NYPD officers for calling the department “racist” in another social media post.

While Mamdani is a member of the Democratic Socialists of America, he’s said he’s running on his own distinct platform and does not embrace all of the activist group’s priorities, which have included ending mandatory jail time for certain crimes and cutting police budgets.

NYC’s first Muslim mayor

Mamdani leaned into his faith amid the anti-Muslim rhetoric that marked the campaign’s final weeks.

Outside a Bronx mosque in late October, he spoke in emotional terms about the “indignities” long faced by the city’s Muslim population and vowed to further embrace his identity.

“I will not change who I am, how I eat, or the faith that I’m proud to call my own,” he said. “But there is one thing that I will change. I will no longer look for myself in the shadows. I will find myself in the light.”

Famous filmmaker mother

Mamdani was born in Kampala, Uganda, to Indian parents and became an American citizen in 2018, shortly after graduating from college.

He lived with his family briefly in Cape Town, South Africa, before moving to New York City when he was 7.

Mamdani’s mother, Mira Nair, is an award-winning filmmaker whose credits include “Monsoon Wedding,” “The Namesake” and “Mississippi Masala.” His father, Mahmood Mamdani, is an anthropology professor at Columbia University.

Mamdani married Rama Duwaji, a Syrian American artist, earlier this year. The couple, who met on the dating app Hinge, live in the Astoria neighborhood of the city's borough of Queens.

Once a fledgling rapper

Mamdani attended the Bronx High School of Science, where he cofounded the prestigious public school’s first cricket team, according to his legislative bio.

He graduated in 2014 from Bowdoin College in Maine, where he earned a degree in Africana studies and cofounded his college’s Students for Justice in Palestine chapter.

After college, he worked as a foreclosure prevention counselor in Queens, helping residents avoid eviction, a job he says inspired him to run for public office.

Mamdani also had a notable side hustle in the local hip-hop scene, rapping under the moniker Young Cardamom and later Mr. Cardamom. During his first run for state lawmaker, Mamdani gave a nod to his brief foray into music, describing himself as a “B-list rapper.”

Early political career Mamdani cut his teeth in local politics working on campaigns for Democratic candidates in Queens and Brooklyn.

He was first elected to the New York Assembly in 2020, knocking off a longtime Democratic incumbent for a Queens district covering Astoria and surrounding neighborhoods. He has handily won reelection twice.

The democratic socialist’s most notable legislative accomplishment has been pushing through a pilot program that made a handful of city buses free for a year. He’s also proposed legislation banning nonprofits from “engaging in unauthorized support of Israeli settlement activity.”

Mamdani’s opponents, particularly Cuomo, dismissed him as woefully unprepared for managing the complexities of running America’s largest city.

But Mamdani framed his relative inexperience as a potential asset, saying in a mayoral debate he’s “proud” he doesn’t have Cuomo’s “experience of corruption, scandal and disgrace.”

Viral campaign videos

Mamdani used buzzy campaign videos — many with winking references to Bollywood and his Indian heritage — to help make inroads with voters outside his slice of Queens.

On New Year’s Day, he took part in the annual polar plunge into the chilly waters off Coney Island in a full dress suit to break down his plan to “freeze” rents.

He interviewed food cart vendors about “Halal-flation” and humorously pledged to make the city’s beloved chicken over rice lunches “eight bucks again.”

In TikTok videos, he appealed to voters of color by speaking in Spanish, Bangla and other languages.

During his general election campaign, the viral clips were joined by talked-about television commercials — with on-theme ads that aired during “The Golden Bachelor,” “Survivor” and the Knicks' season opener.

Pro-Palestinian views

A longtime supporter of Palestinian rights, Mamdani continued his unstinting criticism of Israel — long seen as a third rail in New York politics — through his campaign.

Mamdani has accused the Israeli government of committing genocide against Palestinians in Gaza, and has said Israel should exist as “a state with equal rights” for all, rather than a “Jewish state.”

He was hammered by his opponents and many leaders in the Jewish community for his stances, with Cuomo accusing Mamdani of “fueling antisemitism.”

After facing criticism early in the race for refusing to denounce the phrase “globalize the intifada,” Mamdani vowed to discourage others from using it moving forward. He also met with rabbis and attended a synagogue during the High Holy Days as he courted Jewish voters.

In his victory remarks Tuesday, he pledged that under his leadership, City Hall will stand against antisemitism.