The annual poetry congress in Tehran, held last Monday, included what state-owned controlled media have described as an “historic literary event” which, according to one establishment literary commentator, Muhammad-Ali Mojahedi, electrified those present.

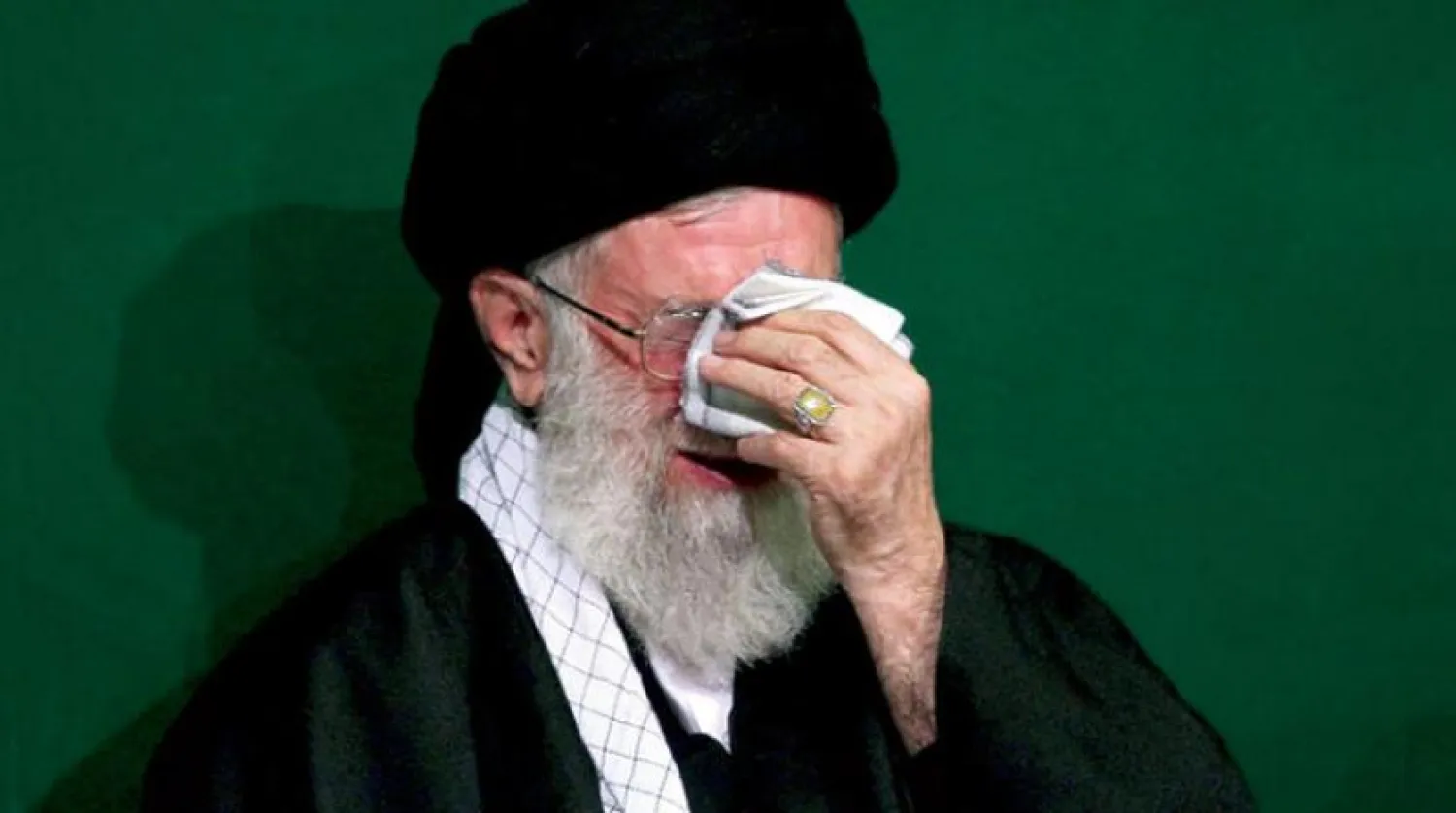

The “event” was the public reading of a new ghazal (sonnet) by the Supreme Guide Ayatollah Ali Khamenei whose poetical ambitions date back to his early youth more than 60 years ago. He has often said that he wished he had spent more time and energy on his poetry rather than on politics and in anecdotal accounts of his life has depicted himself as a disciple of such great contemporary poets as Amiri Firuz-Kuhi and Muhammad Qahreman.

However, still unsure of how the public might receive his poetry, Khamenei, who uses “Amin” as his literary sobriquet (takhallos in Arabic) has always shied away from publishing a diwan or even reciting his poems in public. But because few poets could resist the temptation of reading his work to others, the “Supreme Guide” holds occasional private recitals of his poetry for a handful of confidants who have sworn never to reveal to others what they have heard.

Thus last Monday was a rare occasion when Khamenei overcame his fear of not pleasing an audience agreed to have his latest work recited to an audience of fellow poets and aspiring poets.

To be sure, Khamenei isn’t the first political leader to harbor poetical ambitions. Both Josef Stalin and Mao Zedong wrote poetry. And Iran’s own Nassereddin Shah spent more time committing poetry than running the country.

But how good is Khamenei’s new ghazal?

To start with, by classical standards it is one line (beyt) short. The standard classical ghazal consists of a minimum of seven lines (abyat) and a maximum of 13. Khamenei has stopped at six lines. Next, Khamenei’s work moves away from the classical ghazal’s thematic unity in diversity in which each line seems to have an independent content while indirectly linked to the content of other lines.

Here, Khamenei geos for a very modern introspective style in which all the lines (abyat) come together to depict the poet’s mood at a certain moment in time.

But what is this mood? As you would see in the translation of the poem which follows, the ghazal depicts the poet as a disturbed person, divided against himself and struggling with the pull of events.

Khamenei has chosen one of the favorite meters (owzan in Arabic) of the great Persian Sufi poet Molawi (known in the West as Roumi), originally developed by Arab poets of the pre-Islamic era including Labid, Zuhair Ibn Abi-Salma and the black slave warrior Antar Ibn Shaddad. This meter is extremely rhythmic and pre-Islamic (Jahiliyyah) poets regarded it as suitable for war poetry being recited with the beating of drums.

In contrast, Molwai and other Persian poets, for example Athireddin Akhsikati and Khaju Kermani used it to accompany Sufi-style dance that includes gyration to the beat of a small drum (tablah). The meter (wazn) is the double alternation of one long and one short syllable: mufta’alan mufta’al, mufta’alan mufta’al, perfect for inciting warriors to combat or inspiring Sufis to gyrate.

In his ghazal, Khamenei has gone for an interesting rhyming scheme usually used by Persian poets to evoke sorrow.

The rhyme in question uses words that contain the Arabic letter M (mim) twice like two wings of a wounded bird, inspiring a sense for forlornness. At the same time because the letter “mim” isn’t a loud one it helps create an atmosphere of intimacy, as if the poet was whispering his sufferings in your ear. However, the poet cannot keep up the chosen rhyme scheme, as for example, Amiri- Firuzkuhi or Hushang Ebtehaj would, all through the ghazal. Thus three of the six lines (abyat) stick to the scheme while three others offer words that contain only one “mim”. In two lines the Arabic letter L (lam) replaces the letter “mim”.

Such imperfections, however, don’t do much damage to the ghazal as a whole which is well crafted in terms of prosody. The poem also evokes some of the classical concerns of the Sufis as to how to liberate oneself from one’s earthly reality in the hope of reaching for a greater transcendental truth.

Khamenei uses many clichés of classical Persian poetry, including being “drunk, utterly gone”, “pure wine”, and “the skirt of love.”

Reading too much politics in this short ghazal may be out of order. However, one cannot ignore the fact that the man currently ruling Iran appears unsure of his impact on life, feels he is the victim of some unspecified injustice and sees a schizophrenic “Id” (in the Freudian sense) that is “sometimes pure wine, sometimes deadly poison.”

He craves after purity but sees himself as a “synthetic mix” which makes him cry. At times, this divided “Id” plants his claws into his own “bleeding heart”. At other times it attacks his “own flock like a wolf.”

All in all, I liked the ghazal, maybe because I am a sucker for classical Persian styles of poetry.

But, here is the translation of the ghazal by the” Supreme Guide”, judge for yourself:

I am disturbed by the cacophony in me

I wish I could get out of self-absorption

Pulls me this way and that like a straw

Obsession with this and that, capriciousness of the self

I have plunged my claws into my bleeding heart

Like a wolf I have attacked my own flock

At times I am pure wine, at others deadly poison

I cry out of the synthetic mix that I am

I am a child, resting my head on the skirt of love

Hoping that lullaby will release me from my ego.

I am drunk, utterly gone, Amin, heedless of was and is

From whom can I seek redress for the injustice done to me?