Asharq Al-Awsat will exclusively publish excerpts from a new memoir, “Al-Qarar” (The Decision), by former Jordanian Prime Minister Mudar Badran. The book will be officially released in Amman on August 17. The memoirs are filled with developments and stances that will be revealed for the first time, including moments Jordan experienced in the last quarter of the 20th Century.

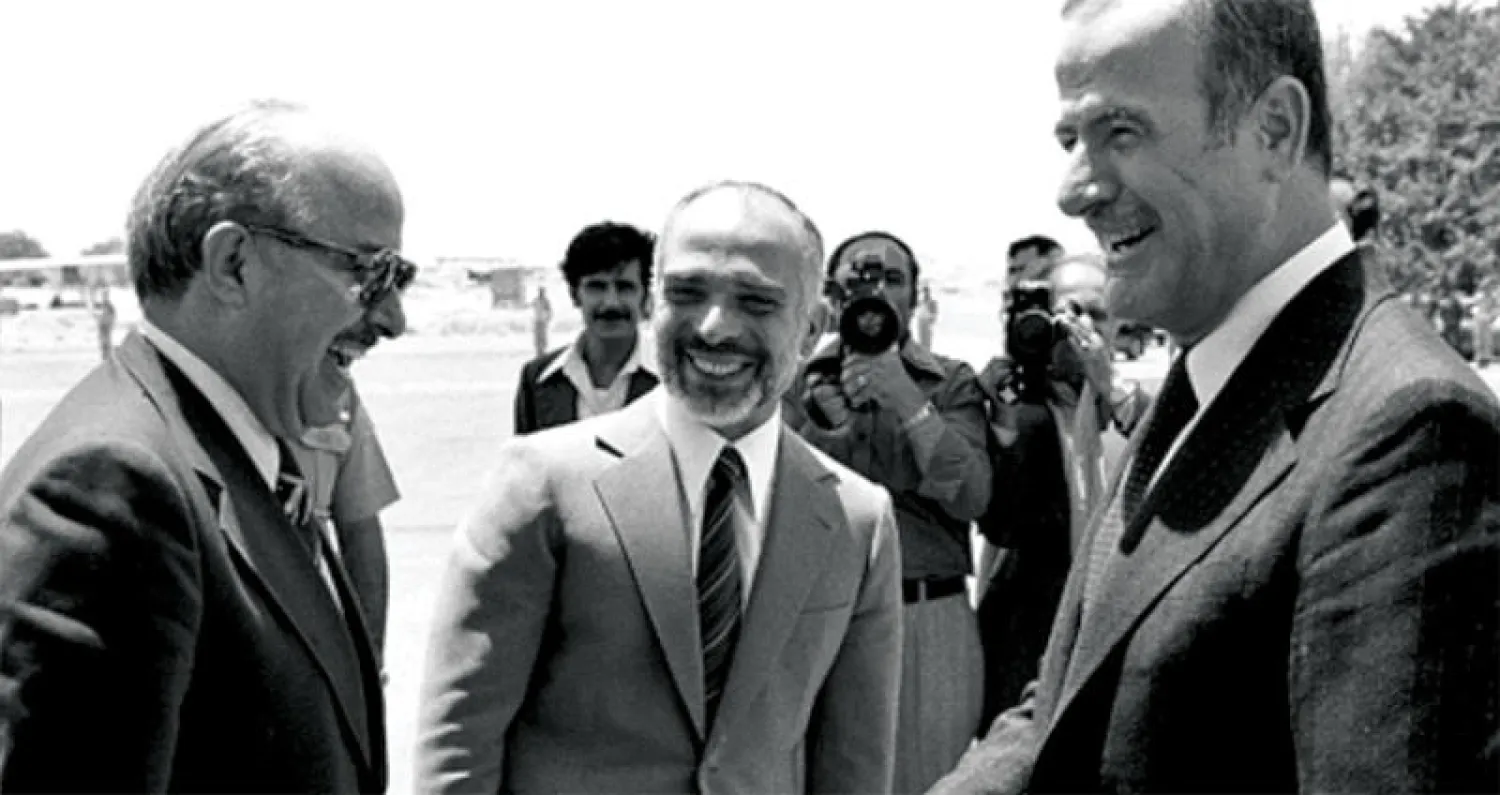

Badran previously served as head of general intelligence in the late 1960s. He then headed the royal diwan and was close to late King Hussein. In this first excerpt, he details the efforts Jordan exerted to avoid any Iraqi military action against Kuwait. He recalled how these efforts sought to find an inter-Arab solution that would guarantee Iraq’s withdrawal from Kuwait. He also detailed the discussions King Hussein held with then American President George Bush in the buildup to the war to liberate Kuwait.

On May 2, 1990, an Arab summit was held in Baghdad. In a closed-door meeting for the leaders, Saddam Hussein addressed each of the United Arab Emirates and Kuwait. The meeting was tense and the summit frankly spoke of the Iraqi-Kuwaiti disputes.

Saddam spoke of how the Kuwaitis had drilled for oil in the joint Rumaila field on the border with Iraq while Baghdad was preoccupied with its war with Iran. I wondered at this comment and predicted that it would spark a major crisis between the countries.

We were close to the Iraqis and were exhausted by our attempts to convince them against allowing the situation between them and the Kuwaitis to escalate into military action. Even though we were accused of knowing of Iraq’s occupation of Kuwait, we absolutely had no prior knowledge of this intention.

It is true that the signs were very clear to us and we openly spoke about this with the late Saddam. We tried to warn him against taking any reckless actions on this front, but we had no idea that he intended to invade Kuwait or that that development would change our region. We believed that Saddam was simply making political maneuvers in wake of previous comments by Abdulkarim Qassem that Kuwait was part of Iraqi territory and his threats that it will take it back. The Arab League, in response, sent military troops to Kuwait.

I was aware that Saddam, whom I knew very well, had sensitive points that he would not negotiate over. I had studied Saddam’s character and spent a long time analyzing him. In the first three months that I met him, I remained silent during our meetings just so I could analyze his character. He is a man who reacts in extremes when it comes to dignity or magnanimity. During our last visit to Baghdad, just before the occupation of Kuwait, Saddam had dispatched his prime minister Saadoun Hammadi to Kuwait where he was made to wait two days before meeting the Emir. This only compounded the situation. We tried to mend the rift between brothers, but these attempts were too little too late.

Days before the occupation of Kuwait, Arab capitals witnessed a flurry of bilateral meetings and visits. I remember very well that on July 29 and 30, 1990, two separate meetings were held. One took place in Saudi Arabia between Kuwaiti Crown Prince Saad Al-Abdullah Al-Sabah and Iraqi Vice President Izzat Ibrahim al-Douri. Saddam’s orders to his deputy were clear: “If Kuwait agrees to the Iraqi demands, then that’s all and good. If not, then return (to Iraq) immediately.”

The second meeting took place between King Hussein and Saddam in Baghdad. I was late to the meeting because Egyptian Prime Minister Atef Sedky had made an official visit to Amman. As soon as he departed, I headed to Baghdad where I at arrived at 10 pm. The official dinner was over and I sat down with King Hussein, who informed me of the tensions between Saddam and Kuwait. I requested that I meet with Saddam to warn him against being reckless and hasty and indeed I did – with King Hussein - before our departure to Kuwait

Later, as we were in the car riding towards the airport, I told then first Iraqi Vice President Taha Yassin Ramadan that I had never seen Saddam that angry before. I added that they must convince him against being reckless because that would harm all of our interests.

During a later visit during the occupation of Kuwait, Saddam told me in wake of my conversation with Ramadan: “You want Abou Nadia (Ramadan) to enlighten me. I am the one who enlightens him during Revolutionary Command Council meetings.” Ramadan was the only member of the Iraqi leadership who had opposed Saddam’s war on Kuwait.

After our Iraq trip, we arrived in Kuwait where I remained at the airport. There King Hussein met with Emir Sheikh Jaber Al-Ahmed Al-Sabah and it appeared to me that the situation was headed towards more tensions and that Saddam was bent on invading Kuwait, which had not changed its position. I did not attend the late King’s meeting with the Emir, but I stood in wait with then Kuwaiti Foreign Minister Sheikh Sabah Al-Ahmed Al-Sabah. I asked him if it was true what the Iraqis were saying that Kuwait had drilled for oil in the joint field between their countries. He said it was and that Kuwait was ready to reach an understanding over the issue. He revealed that they had produced 1,700 barrels per day and that Saddam said that the figure was 2,000 and even more.

I realized at that moment that Saddam will not leave the issue at this and because he was involved militarily on the Iranian front.

After our return to Jordan, I asked the parliament to hold a secret meeting. I informed them that I would not be surprised if Iraq occupied Kuwait. The meeting was held on a Wednesday. The next day, August 2, 1990, Saddam invaded Kuwait and seized it in four days.

After the occupation, we threw ourselves into convincing Saddam to withdraw. We worked tirelessly in pressuring him to prevent any military action led by the United States and its allies.

During one of our meetings, I managed to put Saddam on the spot and pressured him to withdraw. “You did not intend to invade Kuwait,” I told him. He did not like my comment, but acknowledged that it was true. He revealed that a military commander had headed to the Iraqi-Kuwaiti border and informed him that no Kuwaiti troops were amassed there. At this, he asked Saddam: “Should I proceed towards the capital?” And Saddam replied: “Yes” and this is what happened. Of all the reasons that could have led to the catastrophe, I was shocked that Saddam would make up his mind based on the erroneous judgement of a brigade commander.

Jordanian mediation

King Hussein kept up his efforts to pressure Saddam to withdraw from Kuwait. He announced that he had received the blessing of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak and Saudi King Fahd bin Abdulaziz to accept his mediation to pressure Saddam to pull out in return for holding a small summit in Jeddah. King Hussein flew to Baghdad the next day to seal the deal, which called for holding the summit as soon as the Iraqi leadership takes the decision to immediately withdraw from Kuwait.

At this point, it seemed that the issue was going to be completely resolved. King Hussein received the Iraqis’ approval to hold the Jeddah meeting. Saddam also informed King Hussein that he will refer to the party leadership to take the withdrawal decision. This was at exactly 4 pm. Saddam said that Izzat Ibrahim would call to deliver the news about the pullout. We understood that the Iraqis were flexible about negotiations over the withdrawal. We arrived at Amman’s Marka Airport at 5:15 pm.

King Hussein made remarks to CNN. After that Egypt and Saudi Arabia went back on their decision to attend the small summit and expanded Arab summit. Saddam commented: “If the Arab League decides to condemn Iraq, then everyone will stand his ground.”

The agreement with Hosni Mubarak called for postponing the Arab League meeting to allow the mediation to succeed. At 11 pm, the League made its announcement. We had told our Foreign Minister Marwan al-Qasim to inform the meeting to wait for important news at 10 pm when the Revolutionary Command Council would announce its pullout from Kuwait and agree to attend the Jeddah summit. However, when the Arab League announced its decision, we realized that the situation was greater than our diplomatic moves. At that point, our ambassador in Egypt sent a draft resolution to the Arab League, which was set to meet in Cairo on August 5.

The Cairo meeting was indeed held, but it seemed futile because the Egyptians had earlier declared that their mind was set over the crisis and that they would be sending troops to Hafar al-Batin. There no longer was any point to the summit.

FM Qasim had attended the Arab foreign ministers meeting ahead of the summit and informed Saddam that the League was leaning towards condemning the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait and issuing a resolution similar to the Security Council.

The next day, King Hussein was in uproar because the resolution totally disregarded the Kingdom’s mediation. He informed us to inform Qasim that Jordan would express reservations over the resolution.

Jordan was still active in mediating with Saddam. At the summit, we advocated the formation of a small Arab committee that would submit a report that highlights the heart of the dispute between Iraq and Kuwait.

Jordan did not cease its efforts to find an inter-Arab resolution to secure an Iraqi withdrawal from Kuwait. We proposed that we deploy half of our Arab army along the Saudi-Iraqi border and that our army be commanded by the Saudis, along with the Egyptian and Algerian militaries. We were convinced that Saddam would not strike an Arab army, but that he would destroy any foreign one.

Our proposals, however, were at odds with the Gulf position on the developments. This complicated the success of our inter-Arab initiative. It became clear that the Gulf countries’ view was based on the belief that the invasion was the product of prior coordination between Iraq, Jordan, Yemen and the Palestinians. They believed that King Hussein knew in advance of the invasion. In wake of this, the Gulf decided to halt aid to Jordan.

King Hussein viewed Iraq as a new hope and new Arab phenomenon. He was keen for it to end its plight strong and recovered, but he also truly wanted to link an Iraqi pullout from Kuwait to Israel’s pullout from the West Bank and Jerusalem, despite American and British opposition.

Efforts to avert military action

Despite tensions with the US, King Hussein was seeking through diplomatic efforts to avert military action against Iraq. Indeed, we traveled to Washington where we met with President Bush, who informed King Hussein that he will not allow Saddam or anyone else to control oil. Oil, he said, was the future for generations in the US and West. Saddam wanted to control 20 percent of the globe’s oil reserves, which the US viewed as a threat to its national security and therefore, Bush stressed that he would not allow him to violate it.

King Hussein explained during the visit the details of the crisis between Iraq and Kuwait. He added that an Arab solution may delay a war in the region. He also stressed that protecting Saudi Arabia against any Iraqi threat lies in deploying Arab forces to the Iraqi-Saudi border. He renewed his demand that campaigns against Iraq cease and warned that Iraq would retaliate to every American action.

King Hussein’s diplomacy was not limited to Washington. We accompanied him on several trips. We headed to North Africa and Europe. We were informed that Iraqi intervention in Kuwait was the reason for foreign meddling in the region. Britain advocated war because it wanted to topple Saddam. In fact, its position was so extreme and against Saddam’s continued rule of Iraq. We understood that the British did not care who ruled Kuwait after the war as long as Saddam was out of the picture. This view was relayed to us by Margaret Thatcher, who had such a completely dictatorial mindset. It was as if she had just come out of colonizing India.

As for the French, President Francois Mitterrand said he was annoyed by Saddam, but was still working on reaching a peaceful political solution, not a military one. Germany opposed using force and hinted to us that Thatcher was influencing Bush to resort to such an option against Iraq.

We then headed to Baghdad to inform them of our talks. I met Tariq Aziz and his words did not leave room for optimism. But he was not the ruler, so I clung on to some hope. During one of our meetings, we informed the Iraqis that they needed to show more flexibility and that it could be followed by a possible American withdrawal from the region and Gulf and Iraqi withdrawal from Kuwait.

King Hussein held a very frank meeting with Saddam during that visit. They both openly expressed their views and we found out the Saddam was committed to the initiative that Iraq link its withdrawal from Kuwait to the Palestinian cause. He said that there could be no backing down from this demand, because flexibility would be seen as retreat. “There can be no backing down. Kuwait is an Iraqi province. End of discussion,” he said.

Meanwhile, in the Gulf, FM Qasim had embarked on a tour of the region. Qatar did not respond to our messages, so we did not visit it. In Oman, Sultan Qaboos showed some positivity, especially after he did not seem receptive to all American demands. The United Arab Emirates was furious because it believed that King Hussein was advocating one position, while the rest of the world was pursuing another.

In Jordan, this was reflected in the halt in Arab aid. We were facing a difficult economic situation. We turned to Libya for aid, and they asked us if Saddam had given us money from the Kuwaiti central bank. We informed them that the Americans had informed us that Iraq could not open the bank’s vault because it could not crack its computer code.

Days before the strike against Baghdad, I visited Damascus where I met President Hafez Assad for six straight hours. I told him that we had nothing to do with the war and that Syrian-Iraqi relations had improved recently. This in turn supports Jordan against various challenges, significantly the Palestinian cause. I told him that Iraq’s strength favors all Arabs, not just Saddam alone. I asked Assad: “How will the Syrians balance the deployment of their troops at Hafr al-Batin and deployment elsewhere if something were to happen to us on the Israeli front?”

He replied that any Israeli attack against Jordan was an attack against Syria. He said his army will intervene immediately and will not leave Jordan alone to face Israel.

I tried during that long meeting to persuade Assad to reconcile with Saddam. The Syrian leader told me that King Hussein had forced them to confront each other for 14 hours of negotiations at Hafr al-Batin, but the talks failed due to Saddam’s pride. It is this pride that will kill him, he told me.

Our mediation to end the crisis and avert military intervention did not cease. Two months before the war, I headed to Baghdad carrying a message from King Hussein to Saddam. I met with the Iraqi president for 2.5 hours. The message covered latest Russian and French efforts to resolve the crisis. Saddam again reiterated his position that a withdrawal from Kuwait was out of the question.

I sensed that Iraq was headed to war, to which Saddam remarked: “Let it happen. We will not back down. Iraq will not start the war, but if they will. We are highly prepared for it. They are wrong in believing that the war will be short.”

The second of the series of excerpts continues on Monday.