On September 16, 1982, just days after the assassination of President-elect Bashir Gemayel and the Sabra and Shatila massacres, Beirut’s residents heard a call to arms. From the home of Kamal Jumblatt, two men — George Hawi, secretary-general of the Lebanese Communist Party, and Mohsen Ibrahim, leader of the Organization of Communist Action — issued an appeal to resist the Israeli army that had pushed into the capital.

By month’s end, the people of Beirut were stunned once more: loudspeakers mounted on Israeli army vehicles broadcast a message that seemed almost unreal. “People of Beirut,” the occupiers announced, “do not fire on us. Tomorrow we will withdraw. We have no missions inside the city.”

That very withdrawal, to Khaldeh on the city’s southern edge, filled Beirut with pride. Its residents had seen their own sons and daughters strike fear into one of the region’s most powerful armies. Yet almost no one knew who had orchestrated the string of seven attacks, carried out over just eleven days, that had forced the invaders to retreat.

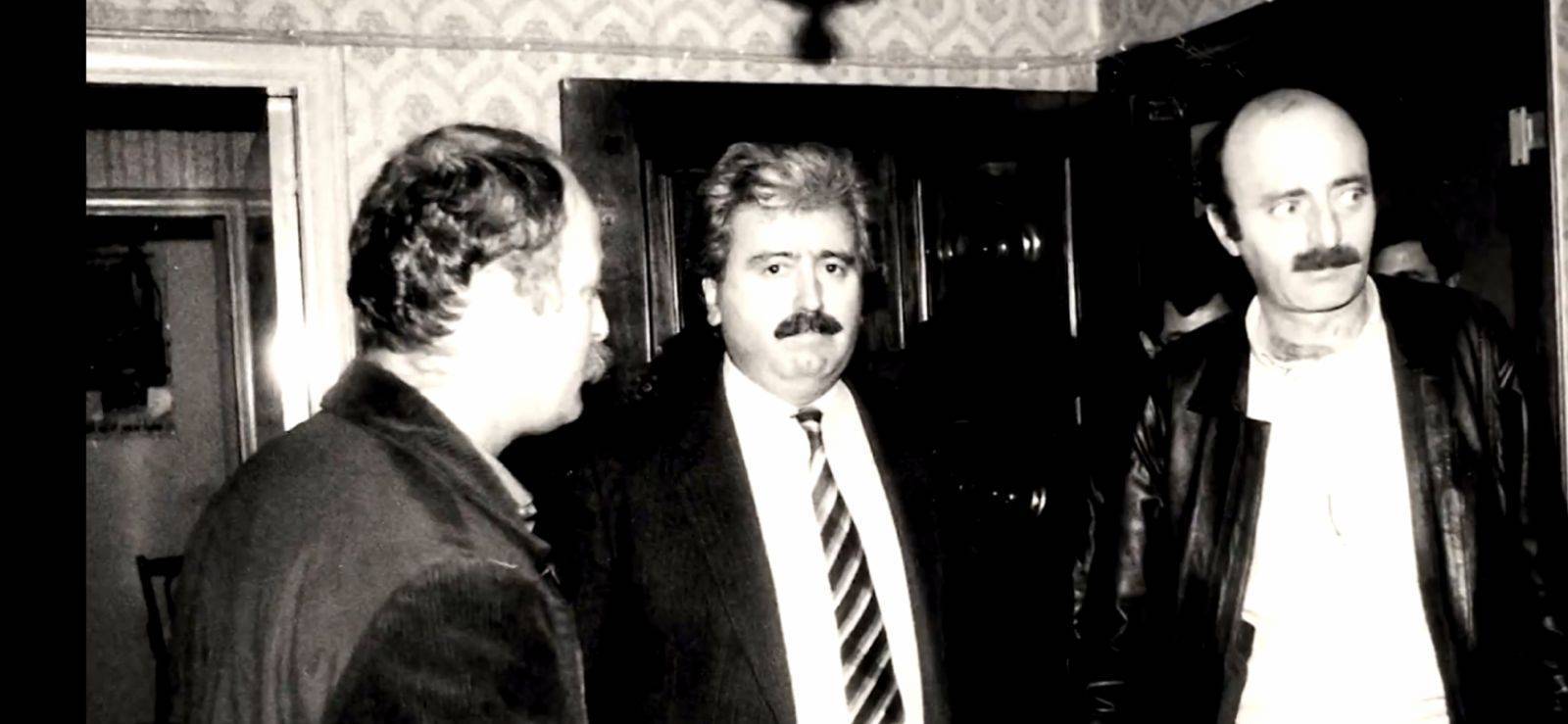

The answer was Elias Atallah — then a young political bureau member of the Communist Party, serving as its military commander. He had been secretly tasked with founding and coordinating the Lebanese National Resistance Front (Jammoul). In his telling, only three people knew of his role: Hawi, Ibrahim, and Khalil Debs.

The early days

In the second of a three-part interview with Asharq Al-Awsat, Atallah said he began by selecting 21 young men, arming them, and dividing them into three sectors across Beirut. Israeli intelligence had little insight into their plans, which allowed Atallah to scout attack sites personally and sometimes even shadow operations from nearby streets.

The first strike came on September 20, 1982, when two fighters hurled grenades at a group of Israeli soldiers gathered around a fire near a pharmacy in the Sanayeh district. The attackers escaped unharmed; the Israelis suffered casualties.

Soon after, two armored vehicles were ambushed near the Patriarchate area with B-7 rockets. Another team assaulted Israeli troops occupying the PLO’s former offices on Mazraa Street. But it was the fourth attack that sent shockwaves: two young men walked into the famed Wimpy Cafe on Hamra Street and shot dead an Israeli officer and two soldiers as they sipped coffee.

Three more operations followed in rapid succession: in Tallet al-Khayyat, on the Selim Salam bridge, and outside the Alexander Hotel in Ashrafieh. Beirut had become a battlefield where the occupier was no longer untouchable.

The attempt on Antoine Lahd

Perhaps the most audacious operation came years later. On November 17, 1988, General Antoine Lahd, commander of the Israel-backed South Lebanon Army, was shot at close range by a young woman, Soha Beshara.

Atallah recalled: “Soha came from a communist family. She was athletic, often visited her village near Marjeyoun, and never raised suspicion. She befriended Lahd’s wife, who asked her to tutor their children privately at home. For months she taught lessons, drank coffee with the family, and gained their trust. That’s when the idea emerged.”

Only three people knew of the plan: Atallah, Hawi, and a young man living in Belgium. Atallah admitted he was uneasy: “I told her this wasn’t just about military difficulty. Could you really look him in the eye and pull the trigger? It wasn’t to discourage her, but I felt the operation lacked humanity. Still, she was determined.”

Soha fired several bullets into Lahd, wounding him critically, but he survived miraculously after being airlifted to Israel. She was captured instantly. Imprisoned in Khiam, she endured for 10 years before being released in 2000 through French intervention and at the request of then Prime Minister Rafik Hariri.

Atallah revealed that he tried to intercept her release convoy: “I believed she should be returned to us, not paraded elsewhere. But we were outmaneuvered; they took a different route.”

Walid Jumblatt and the resistance

Was Walid Jumblatt, Atallah’s longtime ally, aware of his coordination of operations? Atallah replied that Jumblatt was not directly involved: “I informed him later. He was uncomfortable, but told me: ‘If you need anything, I will help. But don’t let operations come too close to Mokhtara [his stronghold].’”

Jumblatt even offered logistical support, though without formally endorsing the resistance. To Atallah, this reflected the careful balance Jumblatt maintained in Lebanon’s fractured landscape.

How Jammoul was undermined

The resistance’s decline was gradual, not sudden. One early sign came when the Soviets supplied the movement with five sniper rifles, which are powerful weapons capable of reaching targets at a kilometer’s range. The rifles arrived in Syria but were seized by Hafez al-Assad’s regime. Damascus denied receiving them; Moscow confirmed they had been delivered.

Soon tensions arose with the Amal movement, led by now parliament Speaker Nabih Berri. “The hostility wasn’t uniform,” Atallah recalled, “but at the leadership level, it was never friendly. Information leaks and betrayals followed - and behind it, I am convinced, stood the Syrian regime that had already silenced Imam Moussa al-Sadr.”

Ghazi Kanaan’s ultimatum

In February 1985, Atallah and Hawi were summoned to meet General Ghazi Kanaan, Syria’s intelligence chief in Lebanon. “He began with endless praise, saying that we were disciplined, brave, ideological... But the more he praised, the more uneasy I became,” Atallah recalled.

Kanaan then revealed his demand: “President Assad says the resistance is not a Lebanese affair but a strategic Arab cause. It must be directed accordingly. From now on, no operation will be carried out by one side alone. We will form a joint command. And you must merge with Hezbollah.”

Indignant, Atallah pushed back: “Yesterday one of our fighters was shot in the back in the South. We know Hezbollah did it. How can you ask us to join them? We will not be chess pieces.”

Kanaan slammed his hand on the table, sending coffee cups flying. “You will pay dearly,” he thundered. And he left without farewell.

Atallah and Hawi knew they had crossed Assad’s red line. “When he invoked ‘His Excellency the President,’ we understood this came directly from Hafez al-Assad. Refusing meant punishment.”

Assassinations begin

The punishment soon followed. “We paid first in blood,” Atallah said. “They began killing our leaders. Between 1986 and 1987 alone, some 30 of our cadres were assassinated.”

Among them were Khalil Naous, a central committee member respected across Beirut; Hussein Mroueh, the 87-year-old intellectual shot in his wheelchair; Hassan Hamdan, better known as the philosopher Mahdi Amel, whose lectures drew students from all faculties; and Suhail Toula, editor-in-chief of al-Nidaa.

The message was unmistakable. At Hamdan’s funeral, Kanaan himself appeared. “He didn’t come to offer condolences,” Atallah recalled bitterly. “He told our leaders to their faces: ‘Was it necessary to bring yourselves to this?’ It was as if he were signing his work.”

Despite the losses, Jammoul pressed on. “By 1988, we were still averaging three to four operations daily. Israeli deaths totaled around 300. And we never harmed Lebanese civilians, not once. That was our principle.”

Numbers and losses

In total, Atallah estimated the resistance carried out more than a thousand operations. About 160 fighters were killed. “We were hunted, constantly. But we kept going,” he said.

Syrian interference grew more direct. Kanaan stoked clashes between the resistance and Amal, sparking fierce battles in Beirut. Syrian tanks rolled in from Aley and Sawfar. At one point, Atallah recalled, Communist Party offices were stormed without cause.

Exile and Moscow

Atallah also recounted being effectively exiled. After Israeli forces discovered their radio frequencies, he traveled to Moscow seeking technical help.

There, he was told he would remain six months - a decision, he later learned, that had been requested by Syrian intelligence. “Muhammad al-Khouli, Assad’s air intelligence chief, told George Hawi: ‘Either you find Atallah’s corpse on the street or you send him away.’ They chose exile. I refused and returned home.”

The final blow

The beginning of the end came with an Israeli strike on the party’s headquarters in Rmeileh, Atallah’s hometown on the Chouf coast. Intelligence had warned of the threat. The central committee was due to convene there, but Atallah urged evacuation.

The Israeli attack, using a vacuum bomb, destroyed the compound. Only two were killed, spared by the prior evacuation. But morale was shattered. “That was the heaviest blow,” Atallah admitted.

Asked whether Jammoul was penetrated, Atallah conceded only “very limited” infiltration, by an Israeli agent. He denied Arab involvement, and said the Soviets never pressured him personally to cooperate with the KGB.