Months before his assassination, former Hezbollah Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah believed that the “support war” his party had launched against Israel in October 2023 in support of Gaza would remain within the limits of the “rules of engagement”. He believed that Iran would not allow four decades of “Islamic resistance” in Lebanon to fall easy prey to the enemy.

However, a series of wrong calculations prevented the party from taking decisive decisions during the conflict, which by September 2024 had turned into an all-out war.

This report reveals how Israel’s assassination of major Hezbollah leaderships effectively cut off Nasrallah from knowing every detail of what was happening on the ground. Field leaders appointed to replace the slain ones did not have enough information. Others have speculated that the party’s problem did not lie in the commanders, but in the loss of rocket launcher operators, who were a “rare commodity” in the party and the war.

Asharq Al-Awsat interviewed a number of Lebanese and Iraqi figures, who were in touch with the Hezbollah leadership in 2024, for this report to help fill in some gaps in the various narratives that have emerged related to the buildup to Nasrallah’s assassination in September 2024.

Lebanese authorities say 3,768 people were killed and over 15,000 injured in the war, while Israeli figures have said that Hezbollah lost around 2,500 members in over 12,000 strikes.

War within limits

In the first weeks of the war, Hezbollah was convinced that the “rules of engagement” on the ground would remain in place and that it would not turn into an all-out war, revealed a Lebanese figure who was in close contact with party military commanders.

Speaking to Asharq Al-Awsat on condition of anonymity, he stated that Nasrallah would tell meetings with influential party officials that the war would be limited to border skirmishes with Israel, as had happened in the past.

One leading Hezbollah member said the party believed that Iran would be able to “set the deterrence in the war and reach a ceasefire through maneuvering in its negotiations” with the West, added the Lebanese figure.

“The party was waiting on Iran to restore balance in the war that was tipped in Israel’s favor and to eventually reach a ceasefire without major losses,” he went on to say.

Iranian officials, led by Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, have always said that Tehran would not abandon its allies. Nasrallah himself had always credited Iran with supporting his party financially and with weapons.

Three commanders

Speaking to Asharq Al-Awsat from his residence in Beirut’s southern suburbs, a Lebanese Shiite cleric said Hezbollah was slow in realizing that it was headed towards all-out war with Israel.

The cleric, who earned his religious studies in Iraq’s al-Najaf, lost four members of his family during the war.

Nasrallah, he added, lost key commanders who were his eyes and ears on the field.

Whenever Israel killed a field commander, it was as if Nasrallah “lost an eye that helped him see clearly. He was obsessed with following up on field developments” and Israel was taking these tools away from him, he revealed.

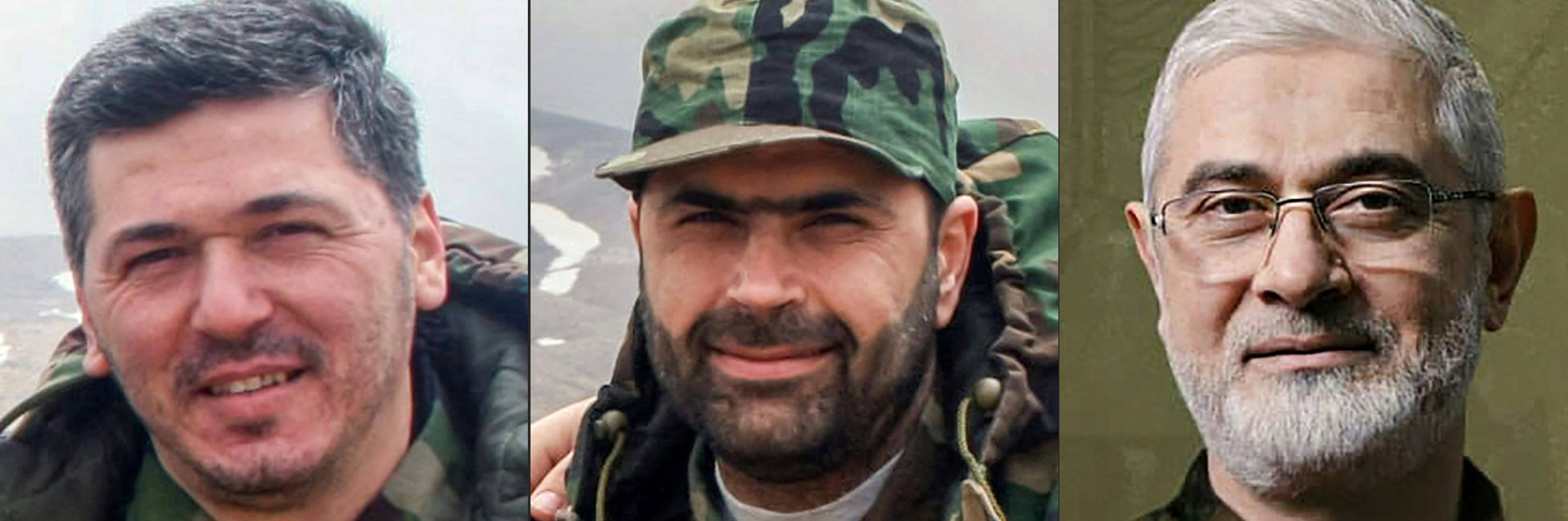

The greatest blows to Nasrallah were the losses of commanders Taleb Abdullah, Ibrahim Akeel, and Wissam al-Taweel.

Taweel was a prominent commander in the party’s al-Radwan unit. Israel killed him on January 8, 2024. Abdullah was responsible for Hezbollah’s operations in the central sector of the border with Israel and stretching to the Litani river. Israel killed him on June 11, 2024, in what the cleric said was the harshest blow to Nasrallah. Akeel was commander of Hezbollah’s military council. Israel killed him on September 20, 2024.

In the end, Nasrallah lost these three commanders and a state of chaos ensued in the operation rooms. “Other commanders on the field complained of how decisions were being improvised because members were acting out of alarm and suspicion instead of discipline,” said Lebanese sources.

Despite these major losses during a period of eight months, Nasrallah and his entourage continued to think inside the box and within the rules of engagement, still ruling out that an all-out war would happen.

Lebanese journalist Ali al-Amin said Nasrallah believed that the party was still capable of militarily deterring Israel and preventing a comprehensive war. He was ultimately wrong.

Secrecy

Hezbollah’s problem lies in Hezbollah itself and how its commanders operate.

Lebanese sources explained that the field commanders killed between January and November 2024 were part of a disconnected chain of command, in that they were not a whole that relayed expertise and information smoothly.

The sources explained further: “When a commander is killed, his replacement does not have access to his predecessor’s field information and details, which are held in secrecy. This was one of Nasrallah’s problems in dealing with the war.”

More interviews with Asharq Al-Awsat revealed that each commander built his own network of relations, methods and information based on his own personal experience as an individual. When he is killed, this network dies with him, along with information about weapons caches or field plans.

At one point, Israeli drones hovering over a Hezbollah unit would have more information about the party than the newly appointed commander, said the cleric.

Israel’s infiltration

Nasrallah first started having doubts that Israel had breached Hezbollah after the assassination of Saleh al-Arouri, former Hamas deputy politburo chief, on January 2, 2024. Wissam al-Taweel was killed that same month.

The cleric said Nasrallah had not expected these assassinations and notably kept silent after they happened.

Later, he chose defense instead of offense, said Al-Amin. He revealed that field commanders had urgently requested a meeting with Nasrallah to call on him to launch an all-out war, because Israel was hunting down their members. Nasrallah adamantly refused.

Instead, the party became more isolated and began having deep doubts. The cleric explained that this is how Shiite movements in particular behave. They isolate themselves for internal reflection.

Security sources said that at the same time, Hezbollah reviewed its communications networks in the hopes of finding the Israeli breach.

A prominent Shiite figure, who has been in contact with Hezbollah since 2015, told Asharq Al-Awsat that the channels of communication with the party changed several times as more and more assassinations took place in Lebanon.

“We would come in contact with a new person every time we needed something from Dahieh (Beirut’s southern suburbs and a Hezbollah stronghold),” he added.

In August 2024, the Iranians asked Iraqi factions to support Hezbollah in its war. The Iraqi leader said they were instructed to make media statements that they were ready to go to war. A month later, Iraq’s Kataib Sayyid al-Shuhada faction said it would send 100,000 fighters to the Lebanese borders, but none did.

Pager operation

The party grew more anxious to uncover how Israel had breached it. Then came the devastating pager operation in September.

The attack isolated leaders from each other and their field networks. Communications within the party were almost dead and at some point, the remaining leaderships even gave up trying to find out where the breach was from.

Following the attack, field units did not hear anything for days from their commanders, revealed the cleric. It took the command a long time to resume contacts.

During that time, a military commander asked Nasrallah if the rules of engagement still stood. Nasrallah did not give a definitive answer, which was unusual for him, according to information obtained by Asharq Al-Awsat.

Nasrallah realized that he was now in an open war that he did not want, but it was already too late, revealed sources from leading officials who had attended important meetings.

Political science professor Ali Mohammed Ahmed tried to explain why Hezbollah refused to change its course of action. He said that maintaining the rules of engagement would ultimately not fall in Israel’s favor.

But what really tipped the war in its favor was its superior technology that Hezbollah had not taken into account.

The final scene

On the day of his assassination on September 27, Nasrallah headed to Dahieh with deputy Quds Force commander in Lebanon Abbas Nilforoushan. We will never know what they discussed. They headed to an underground Hezbollah compound and soon after Israel pounded the site with tons of bunker buster bombs.

Tons of questions were raised the day after in Dahieh and everywhere.

Looking at photos of his slain relatives, the Lebanese cleric said: “It took Hezbollah supporters a long time to recover from the shock. When they did, they asked, ‘who let down whom? The party or Iran? The resistance or Wilayet al-Faqih?’”

Ahmed said Hezbollah operated in a single basic way: it could not quit a war imposed on it, and so, it fought on.

Al-Amin stressed that Nasrallah would never have opened the “support front” without backing from Iran and his conviction that Israel would take into account threats from Tehran’s proxies in Lebanon, Iraq and Yemen.

However, the successive military and security setbacks led to a state of disarray and Nasrallah effectively cut the connection between Iran and Hezbollah, he added. Eventually, both sides realized that they had fallen into a trap.

Ahmed underlined one important development that took place early on during the war. Israel killed the strategic rocket launcher operators. The operators are a “rare commodity” and difficult to replace.

Hezbollah’s problem did not lie in its loss of field commanders, but the rocket operators, he said.

When the party launched hundreds of rockets at Israel a day before the ceasefire took effect, “we realized that it succeeded in replacing the slain operators,” he added.

“No one let down anyone. The problem lies in both Iran and Hezbollah and how they seemingly could not move on from the October 7, 2023 attack. Time was moving, but they were not,” he stated.

Iraqi researcher Akeel Abbas explained that the party and Iran did not grasp the extent of the major change that was taking place, even after Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said that October 7 was like his country’s September 11.

“Everyone understood that the old rules no longer stood and that new ones were being imposed by force,” he told Asharq Al-Awsat.

“Iran was incapable of keeping pace with the major changes Israel was creating. It needed more time to prepare for such a largescale confrontation,” he remarked.