An attractive foreigner once entered a store in Khartoum. The owner never once imagined who it could possibly be. The foreigner noticed the portrait of a senior military figure hanging on the wall. The lady explained that she was his widow and had he been alive, he would have been the president of Sudan.

Zeinab Mustafa was talking about her late husband El-Hadi al-Mamoun al-Mardi who established the Islamic movement in the army and served as a minister after the coup on June 30, 1989. He later died of an illness.

Zeinab did not realize the danger of the visitor and that international intelligence agencies were searching for him. France was seeking his arrest because back in 1975 he killed two members of its security force there and fled. The owner and the foreigner became more acquainted. He explained that he was in Sudan on an important political visit and wanted to meet President Omar al-Bashir or Dr. Hassan al-Turabi. He gave her a book by David Yallop called “Until The Ends of the Earth.” He requested that it be sent to al-Turabi's office.

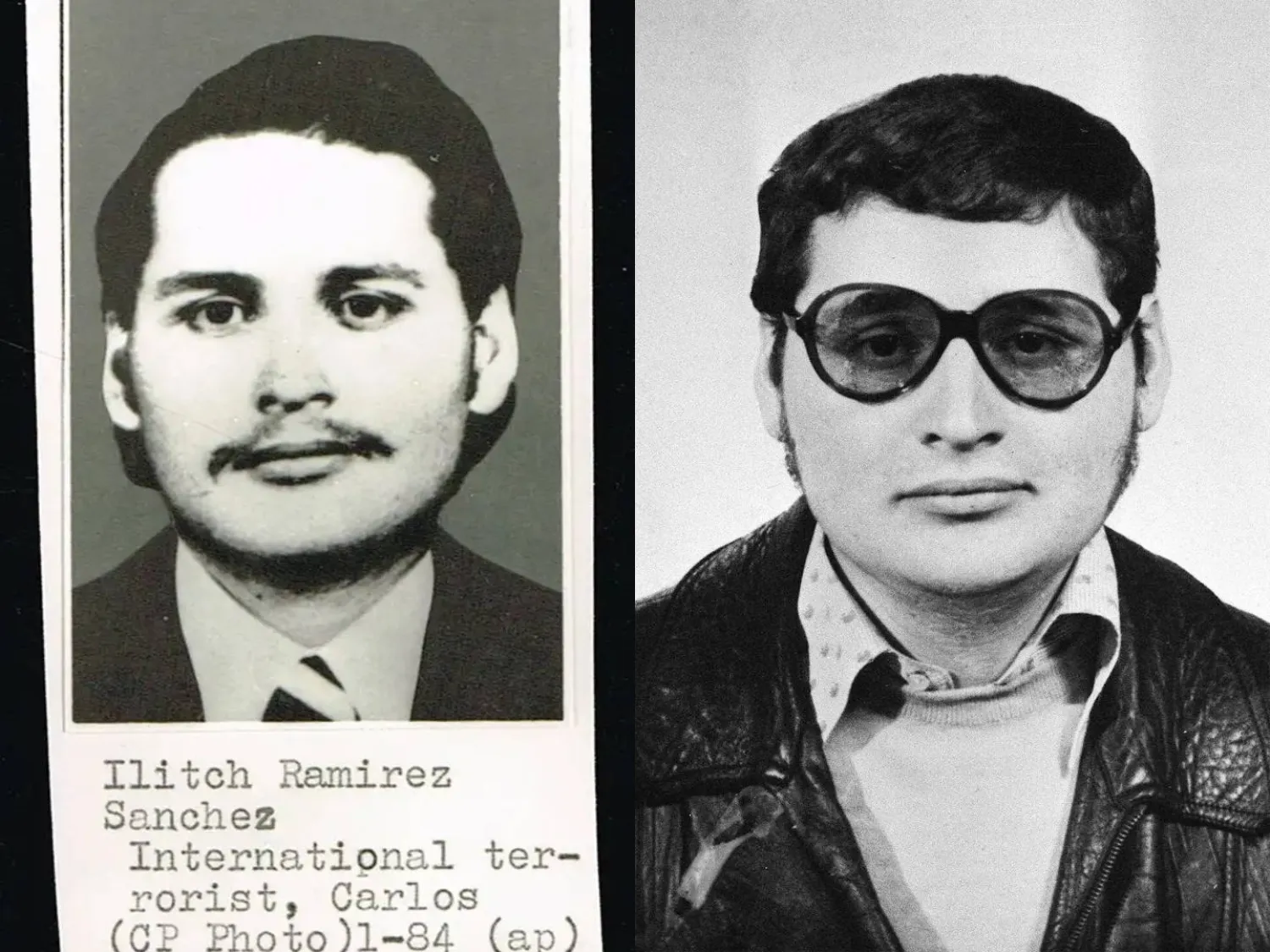

Zeinab took the book and met with Dr. El-Mahboub Abdul Salam, head of al-Turabi's office. He sent the book to al-Turabi, who asked if Yallop was in Sudan. He replied, “No, it was Carlos.” He was shocked. It was none other than the Venezuelan Ilich Ramírez Sanchez, better known as Carlos the Jackal, who was guided by Palestinian plane hijacker mastermind Dr. Wadie Haddad to carry out the kidnapping of the OPEC ministers in Vienna in 1975.

Abdul Salam knows Carlos’ story in Sudan from start to finish. He was tasked with interpreting the discussions that took place between French and Sudanese intelligence that culminated in Carlos being turned over to France on August 15, 1994, where he now lies in prison.

Throughout the 1980s, Carlos roamed all over eastern Europe to evade capture. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, eastern Europe was no longer an option. Baghdad was out of the question, so he landed in Syria, where Hafez al-Assad's regime used him for operations in France and Lebanon. He was later asked to leave the country as Assad sought to polish his image before the West.

Carlos then turned to Moammar al-Gaddafi in Libya. The leader eventually prioritized his relationship with Sabri al-Banna, also known as Abu Nidal, over the burdensome Carlos. Carlos turned to Jordan, which after a while turned him away, so he found himself seeking refuge in Sudan.

Following up on Carlos’ case is an exercise in patience. For two decades, French intelligence agent Philippe Rondot sought his arrest before he eventually succeeded. My profession has allowed me to interview al-Turabi and Carlos. The former told me that Carlos arrived in Sudan “from a country somewhere close to your part of the world” - meaning Jordan. Carlos told me that al-Turabi and Bashir had struck a deal with France for his arrest. Today, I am interviewing Abdul Salam to ask him about Carlos.

“I know all about Carlos’ story in Sudan because I was the interpreter for the Sudanese and French security agencies,” he told Asharq Al-Awsat. He had arrived in Sudan from Jordan in 1993. He entered through the airport using a southern Yemen passport and spent a year in Sudan.

“I had informed Rondot that the passport was fake, but he didn’t believe me, saying it was indeed issued by the Yemeni foreign ministry. Meanwhile, I insisted that Abdullah Barakat – the name on the passport – was not his real name. Sudan discovered that Carlos was on its soil. He indeed was a ‘poisonous gift’ from Jordan as al-Turabi once said. We spent nearly a year persuading him to leave Sudan,” recalled Abdul Salam.

Asked if he had ever met Carlos, he confirmed that he did twice in the final moments before he was flown out of the country.

Asked how come it had taken Sudanese agencies so long to realize that the infamous Carlos was in the country, Abdul Salam explained that his operations were connected to the Palestinians, so he was on the radar of countries that were involved with them, such as Jordan, Syria and Libya. Sudan was not, so he arrived in the country undetected.

Al-Turabi probably found out early on that Carlos was in Sudan, perhaps after his arrival, said Abdul Salam. “He visited our office and requested to meet al-Turabi. The guards at the door were not aware who he was,” he said. Ultimately, he never met with al-Turabi even after he realized that Carlos was in Sudan.

Abdul Salam could not confirm or deny whether Carlos met with Osama bin Laden while they were in Sudan, saying he did not have any information about the issue.

When I interviewed Carlos, he informed me that al-Turabi and Bashir “sold me out.” Abdul Salam said: “He believed that the Islamic regime in Sudan was the same as the one in Iran in that it was hostile to the West and that its leaders would be eager to meet with him and learn from his experience. The regime in Sudan was not like that.”

Carlos presented himself as a Muslim and he tried to offer his services to the regime, revealed Abdul Salam.

Turning to Rondot, Abdul Salam described him as an “extraordinary” man. “It is said that he was born in Tunisia. He was of the ‘black feet’ (pieds-noirs) French colonizers in north Africa. He would occasionally visit during Ramadan and fast the entire month even though he was not Muslim. He once told me that he had spent 30 years on missions. He held a doctorate in sociology and his father was a major sociologist. He had close ties to the Muslim and Arab worlds. He had ties with all Arab intelligence.”

Rondot described Iraqi intelligence as being derived from ideas, while Algerian intelligence only saw what it wanted to see, meaning it was subjective, said Abdul Salam.

Rondot spent some 20 years pursuing Carlos. Abdul Salam told Asharq Al-Awsat that the process to turn over Carlos to France started around four months after he arrived in Sudan, which was in August 1993. “In October, Rondot came to Khartoum following a visit by Sudan’s chief of intelligence to France. Negotiations over Carlos took a long time.”

On how come he was chosen to act as interpreter, Abdul Salam said Sudanese intelligence does boast French speakers, but they wanted to keep the number of people involved in the case limited. Al-Turabi was aware of it and made sure that Sudan respected its agreements with Interpol regarding the arrest of wanted people.

At one point, recalled Abdul Salam, discussions were made over the possibility of returning Carlos to Jordan. Sudan was under international sanctions, and it was best that Carlos be returned to the country he came from. France contacted Jordanian authorities to that end, but they turned down its request.

Asked if Sudanese intelligence had questioned Carlos, Abdul Salam responded: “He was fully aware that the operations that he carried out in the 1970s and 80s were no longer possible. All efforts were focused on how to get him out of Sudan.”

“He was a burdensome guest. Some guests are difficult, but none more so than Carlos who captured the world’s attention and was wanted by a major power like France,” said Abdul Salam. “Several offers were made to him to leave for Uganda, Kenya or eastern Europe. He would say that it was dangerous for him to flee by ship or plane because it was impossible for him to reach Iran, Russia or eastern Europe without passing through regions that were dangerous to him. These discussions were held between him and Sudanese security agencies. It wasn’t that he was maneuvering, but that he was afraid.”

Eventually, Sudan decided that it was time to turn him over to France in line with agreements with Interpol and “preparations for his arrest began immediately,” added Abdul Salam. French intelligence agents soon arrived in Khartoum and French and Sudanese Interpol agencies agreed that the announcement of his arrest would be made six hours after his arrest.

“What ensued is an odd story. Carlos needed to have minor surgery that required follow-up and that’s what happened. The hospital director was unaware of who the patient was. The hospital was informed that the patient needed to be taken out of the facility. The staff were told that he was an Israeli and that he had AIDS. It is said that he was drugged so that he could be handed over to French agents without incident.”

“Throughout that day I was with the chief of intelligence. The tension was in the air until we learned that the handover was a success. I was there to act as interpreter between the Sudanese and French Interpol and saw Carlos as he was being boarded on the plane and that was the end of it.”

Asked whether Sudan received anything in return for aiding in the arrest, Abdul Salam said Paris provided modern training to its security agencies and also provided them with modern cameras and recording equipment.

Rondot later recalled in his memoir that Carlos awoke on the plane when he heard people speaking French around him.

Asharq Al-Awsat asked Abdul Salam about another “burdensome” guest called Osama bin Laden. He acknowledged that he first appeared in Sudan as an “investor”. Later, following his implication in the failed attempt on Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak’s life in 1995, Sudan decided that it was time to “get rid of this guest.”

Upon his departure from Sudan, he warned: “My exit will not protect you from the West and imperialism. You will continue to be targeted,” recalled Abdul Salam. Bin Laden had set up training camps for al-Qaeda members in Sudan, but their activities were “very limited.”

Abdul Salam said that Sudan “is now definitely paying the price” of harboring figures like Carlos and bin Laden. The militias that are now active in the country are definitely products of that point in time.

Carlos’ recollection of the ‘trap’ set up by al-Turabi and Bashir

Years ago, Asharq Al-Awsat asked Carlos at his French prison whether he had made a mistake in heading to Sudan. “Given that I was arrested there, the answer would be yes. I could have headed to various places on condition that I behave.”

“Sudanese authorities were aware that I was there. One of its ministers was on the flight that flew me from Amman to Sudan. He knew who I was,” he added.

He confirmed that Sudan had asked him to leave the country for “security reasons. I did not refuse to leave Sudan, but I refused to cooperate with a trap that was set up by al-Turabi and Bashir. I was alerted to their plan by some sympathizers within the regime in Khartoum.”

Moreover, he revealed that the “United States was the mastermind behind the trap that was overseen by some Gulf figures. The French only took part in the final stage of the operation.”