Dr. Faris Almushrafi, head of the History Department at King Saud University, said Founding Day is not only a moment to recall events or celebrate beginnings, but an opportunity to scrutinize the very tools through which the state defined and asserted itself.

Chief among them is the seal, a compact material document that distills the idea of the state into a single imprint.

Almushrafi told Asharq Al-Awsat that because a seal cannot be read in isolation from its political and administrative context, examining its structure and formulation opens the door to a deeper understanding of the nature of the state that produced it.

The seal attributed to Imam Saud bin Abdulaziz (1229 AH/1814), the third imam of the First Saudi State, was used to authenticate official correspondence, including a letter addressed to the Governor of Damascus in the first decade of the 13th century AH.

The seal bears the central inscription “His servant Saud bin Abdulaziz,” and includes the date 1223 AH, set within a circular frame suggesting completeness and order.

A seal, he said, is not created for ornamentation but for formal recognition. Its presence signals a central authority that needs to document its decisions and correspondence, and an administration conscious of representation. Every sealed letter implicitly declares: this is a state speaking in its own name. Legitimacy is not derived from content alone, but from the imprint affixed to it.

Almushrafi said the phrase “His servant Saud” transcends a personal dimension and enters the language of political legitimacy. The choice of the word “servant” reflects a conception of authority inseparable from religious reference, presenting leadership as a moral duty before it is a political privilege.

This language, he said, is not spontaneous but expresses a model of governance that views political power as incomplete without value-based legitimacy, and sees the state as operating within a system of belief rather than above it.

The seal and state functions: inside and out

The head of the History Department at King Saud University stressed that the seal’s importance increases when one considers that it was used in correspondence beyond the local sphere, addressed to the governor of Damascus.

In this context, the seal became an instrument of external political relations, reflecting the First Saudi State’s awareness of itself as a political actor communicating and defining itself in a formal language recognized in the world of political correspondence at the time. The seal was thus not directed inward only, but also performed a sovereign function externally.

At the same time, the inclusion of the Hijri date on the seal is not a mere formal detail but an indicator of the temporal ordering of administrative work.

A state that dates its documents, he said, understands the importance of sequence, precedence and proof, and recognizes that political action is incomplete without being fixed in time. Here, early features of what could be called the administrative mind of the First Saudi State begin to emerge.

Almushrafi placed the seal in its contemporary regional context, saying its significance becomes clearer when compared with the seals of other Islamic states in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

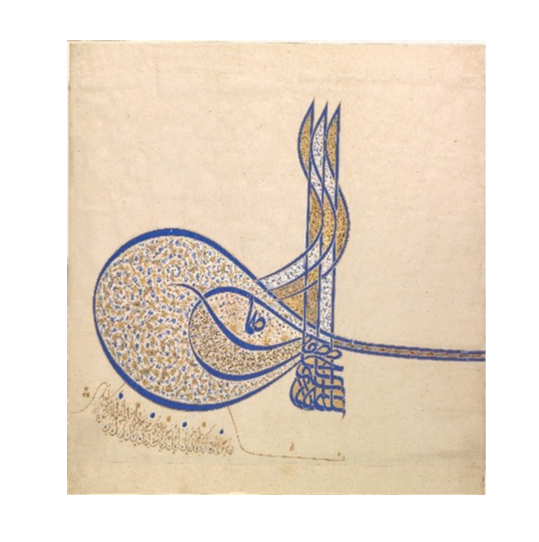

In the Ottoman Empire, the imperial tughra functioned as a composite sovereign signature, bearing the sultan’s name and titles in a dense visual form.

It carried a highly symbolic function that emphasized imperial rank and hierarchical authority before any procedural dimension, turning the seal into a visual declaration of sovereignty as much as a tool of authentication.

In Qajar Iran, official seals were likewise tied to the shah’s name and titles, with a clear emphasis on personal mark and royal legitimacy, making the seal an extension of the ruler’s prestige and symbolic representation of the state more than a neutral administrative device.

In Egypt under Muhammad Ali Pasha, despite early features of administrative modernization, the official seal continued to operate within a language of authority and rank derived not solely from its wording but from the sovereign structure to which the ruler belonged as an Ottoman governor.

Even when Muhammad Ali used the phrase “His servant Muhammad Ali,” Almushrafi said, it did not serve as a foundational definition of legitimacy but functioned as a procedural courtesy within Ottoman writing conventions, softening the tone of rank within the seal while full titles were restored outside it through the system of official ranks and designations - including “Pasha,” a high rank in the Ottoman administrative and military hierarchy, and “Governor of Egypt,” the legally and sovereignly recognized title, along with protocol formulations such as “Governor of Protected Egypt.”

In the Egyptian case, the seal remained as much a declaration of political standing as an instrument of documentation, inseparable from a higher structure of authority defining the ruler’s position.

By contrast, Almushrafi said, the Saudi seal presents a different formulation. The phrase “His servant Saud bin Abdulaziz,” coupled with the Hijri date, suffices to perform the function of official recognition and administrative authentication without symbolic display, inflation of titles, or reference to a higher sovereignty outside the framework of the state itself.

Here, the function of the seal as a state instrument takes precedence over its role as a statement of rank, reflecting a sovereign model based on economy of symbols, clarity of representation and administrative discipline. This distinction, he said, is significant in understanding the nature of the First Saudi State and the logic of its early formation as a state that defines itself through its function and practice rather than through the grandeur of symbols alone.

The seal and the function of the emerging Saudi state

In light of this regional comparison, Almushrafi said the seal of Imam Saud bin Abdulaziz should not be read as an isolated administrative tool but understood in the context of the emerging Saudi state at the time.

It was not formed as a ceremonial or symbolic entity, but as an authority concerned with regulation, implementing rulings, securing its domain and organizing relations between inside and outside.

In this context, the seal becomes a direct reflection of the state’s function: a tool for endorsing decisions, fixing correspondence and regulating political action within a clear legal framework.

The simplicity of the seal’s wording, its economy in titles and its association with the Hijri date all point to a state that sees authority as responsible practice before sovereign display. A state that reduces its symbols to a minimum, he said, prioritizes action over rhetoric, organization over ornamentation and function over representation.

Thus, the seal is read not as a mark of the imam’s person, but as an instrument of a state that operates, communicates, binds and records.

In this sense, the seal of Imam Saud bin Abdulaziz stands as testimony to the nature of the First Saudi State as a state of practice, defining itself by what it executes rather than what it displays, and affirming its presence through administrative and legal discipline rather than symbolic grandeur alone.

Almushrafi concluded that the seal teaches that a state is not read only in battles or major treaties, but in its silent details: a seal, a signature and a linguistic formulation.

On Founding Day, recalling this seal is not merely a celebration of an old artifact, but a conscious reading of a moment that shaped the Saudi state as an organized entity with legitimacy and awareness of political representation.

In this way, the seal becomes a historical testimony declaring: here is a state, and here is an authority that knows itself and knows how to assert its presence.