Nestled in the tri-border region between Iraq, Türkiye, and Iran, the Qandil Mountains have long been shrouded in myth. Difficult to reach due to geography and security, the legends surrounding them gradually took on the weight of truth—especially after Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) fighters established their base there in the early 1990s.

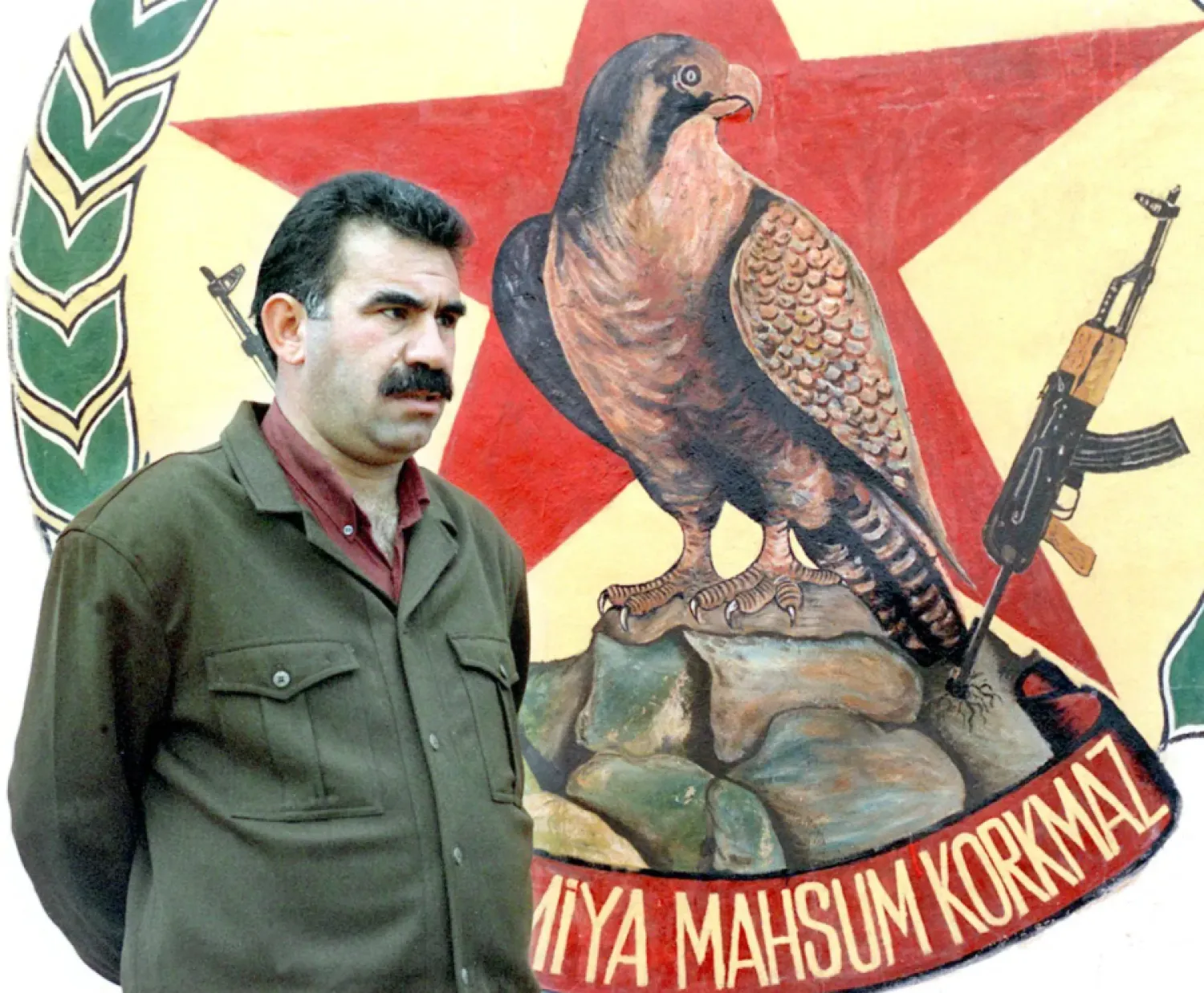

Now, the group is dismantling its structures and laying down arms, following a call by its jailed leader Abdullah Ocalan, who has been imprisoned on Türkiye’s Imrali Island since 1999.

After more than six weeks of attempts to reach PKK insiders in Ankara, Erbil, Sulaimaniyah, Berlin, London, Qamishli and Baghdad, this investigative report evolved from tracing the past and future of the Kurdish “revolutionary” group into a window onto a broader political standoff—one where neither side appears ready to offer trust or guarantees for lasting peace in a region scarred by decades of conflict.

Verifying the real story of Qandil proved one of the most complex challenges of this investigation. Contradictory narratives persist—between what the PKK presents as partial truth, and what is propagated by Turkish authorities or rival Kurdish factions. But despite the scarcity of independent sources, eyewitnesses and individuals close to the Qandil story helped piece together the clearest picture yet of what is unfolding under the shadow of those mountains.

When the late Iraqi President Jalal Talabani met his Turkish counterpart Recep Tayyip Erdogan in March 2008 to discuss the fate of the PKK, the conversation took a sharp turn.

“I am Recep Tayyip Erdogan, not a prophet,” the Turkish leader said, according to Kamran Qaradaghi, a close adviser to Talabani who was present during the meeting.

At the time, Qaradaghi had stepped down as chief of staff at the Iraqi presidency but joined Talabani on the visit to Ankara at the president’s request “to make use of his ties with the Turks,” as Qaradaghi recalls.

Talabani had sought clear answers from Erdogan about the PKK, which Ankara considers a terrorist group. The question he posed was blunt: “Mr. Erdogan, if thousands of fighters come down from Qandil Mountain and we send them into Türkiye, where would they go — to prison, or to their homes?”

According to Qaradaghi, Talabani never got a straight answer.

Qaradaghi recalled the shift in Talabani’s tone as Erdogan refused to give a clear answer about whether PKK militants laying down arms would face prison or freedom.

Realizing he had hit a wall, Talabani changed tactics.

“Are you a good Muslim, Mr. Erdogan?” he asked.

“Of course,” Erdogan replied without hesitation.

“And do you follow the example of the Prophet Muhammad?” Talabani continued.

“No true Muslim would not,” Erdogan responded, now looking slightly perplexed.

Then came Talabani’s clincher: “So why don’t you do what the Prophet did, as the Qur’an says: ‘Enter in peace, secure and safe’?”

Erdogan shot back: “I am Recep Tayyip Erdogan, not the Prophet Muhammad.”

The 2008 meeting between Erdogan and Talabani ended without a breakthrough. Back then, PKK fighters holed up in the Qandil Mountains—where the borders of Iraq, Türkiye

and Iran converge—were already growing disillusioned after three failed ceasefire attempts with the Turkish state.

Seventeen years later, on February 27, 2025, jailed Kurdish leader Abdullah Ocalan issued a dramatic call: he urged the PKK, which he founded, to lay down arms, end its armed struggle with Ankara and dissolve the group altogether.

But many of those interviewed by Asharq Al-Awsat for this report—revisiting key moments in the decades-old Kurdish-Turkish conflict—say the process is likely to be long and fraught with uncertainty.

Even the most hardline among them, including self-described Stalinists, admit the world, and particularly the Middle East, is undergoing unprecedented change.

The physical distance between Ankara and the Qandil Mountains is around 1,000 miles. But the political gap between Erdogan and the PKK’s mountain leadership may be even wider.

PKK cadres believe the ball is now in Erdogan’s court. Yet the Turkish president, known for absorbing high expectations, appears to be playing for time—signaling he wants more before offering a definitive response.

And history suggests the wait could stretch even further. It has before.

This time, Ocalan appears serious about disarmament. The jailed Kurdish leader, once a Marxist revolutionary, has shifted ideologically—embracing the decentralist philosophy of Murray Bookchin—and is said to have been worn down by years of isolation.

“He’s a political actor who learns, adapts and evolves,” said one source familiar with his thinking.

Erdogan, by contrast, is seen as seeking a major victory—“but on his own terms,” according to multiple figures with knowledge of the PKK file in Ankara and Qandil, both supporters and critics.

Black Box

The Qandil Mountains have long been wrapped in myth. With access restricted by both security concerns and forbidding geography, folklore often fills the void left by the lack of verifiable facts. Among the most persistent claims: that PKK fighters recruit children and abduct young men and women into their ranks.

PKK supporters dismiss such accusations as part of a “propaganda war deeply rooted in Turkish state policy.” But security and political officials in both Erbil and Ankara insist the allegations are credible.

Mohammed Arsan, a Kurdish writer sympathetic to the PKK, claims intelligence agencies have worked hard to craft a narrative aimed at discrediting the group. “This is an orchestrated campaign,” he said.

The PKK first arrived in the mountains in 1991, according to Qaradaghi, who joined the Kurdish revolution in the mid-1970s and later observed the rugged Qandil range up close.

Speaking to Asharq Al-Awsat, he said the group capitalized on the chaos following the First Gulf War and the Kurdish uprising against Saddam Hussein’s regime.

“But the real expansion came after 1992,” Qaradaghi said, “when fighters slipped through Iranian territory and crossed the Turkish border, eventually establishing themselves in Qandil.”

Kurdish fighters quickly realized they had secured a rare strategic position in the Qandil Mountains — a natural fortress.

“It’s a harsh, fortified terrain, nearly impossible for ground forces to penetrate,” said Qaradaghi, a longtime observer of the region.

Reaching the area from the nearby town of Raniya, northeast of Sulaimaniya, requires crossing seven mountain peaks on foot, he added — a journey that highlights the natural defenses the group came to rely on.

Much like traditional Leninist parties, the PKK initially structured itself around a rigid ideological core, guided by Ocalan from his prison cell on Imrali Island, where he has been held since 1999.

Over time, however, the group evolved.

“The structure became more flexible,” said Kamal Jumani, a Kurdish journalist based in Europe who specializes in PKK affairs and has visited Qandil multiple times.

“The PKK began as a Marxist-Leninist organization but gradually developed its own independent ideology—democratic confederalism,” he said.

Qandil, he added, serves as the party’s de facto headquarters—“the place where its political and military strategies are shaped and executed.”

At the top of the PKK is the Executive Council of the Kurdistan Communities Union (KCK), an umbrella organization that encompasses the PKK and its sister parties in Türkiye, Syria, Iraq, and Iran, according to Jumani.

The KCK oversees strategic decision-making and political coordination across these branches. In line with the PKK’s gender equality principles, it operates under a co-leadership model, headed jointly by Cemil Bayik and Bese Hozat.

On the military front, the People’s Defense Forces (HPG) serve as the PKK’s armed wing. The unit was led for years by veteran commander Murat Karayilan, while Bahoz Erdal has played a prominent historical role. In addition to military operations, the HPG also implements key decisions—from diplomacy to local governance—in areas under the party’s influence.

Over time, the PKK’s decision-making process has shifted, shaped by Ocalan’s ideological vision of democratic confederalism. “The party is now run collectively from Qandil,” Jumani said.

Qandil: A Regional Watchtower

Nearly five decades after first trekking through Qandil in 1974, Qaradaghi still recalls the mountain range as a kind of “paradise” for eco-tourism—a land of rare birds, wild abundance, and untapped mineral wealth nestled within the offshoots of the Zagros Mountains.

Back then, he climbed seven peaks on foot from the town of Raniya, northeast of Sulaimaniya, to reach the remote terrain. “It’s a rugged, fortified region,” Qaradaghi told Asharq Al-Awsat. “It was hard to reach—and easy to hold.”

Qandil lies at the heart of what was once known as “Greater Kurdistan.”

Historically, it served as a borderland between the Ottoman Empire and Persia’s Badfars province. Today, it functions as a regional watchtower, perched at the intersection of Iraq, Türkiye and Iran.

With the arrival of PKK fighters in the early 1990s, Qandil was transformed. What began as a guerrilla outpost grew into a self-contained enclave—complete with a command hierarchy and sprawling infrastructure.

The group established schools to teach the ideology of Ocalan, along with medical depots, training camps, political offices, and media hubs. There are courts, prisons, and facilities to prepare operatives for missions abroad.

According to PKK sympathizer Arsan, the group built at least seven cemeteries in Qandil, the oldest two within the mountains and the rest scattered between Zab and the broader Zagros range. He estimates that more than 1,000 PKK fighters are buried there.

Today, around 5,000 militants remain in the mountains, although the International Crisis Group places the number closer to 7,000.

Demographically, Qandil’s fighters reflect the broader Kurdish diaspora, drawing members from Türkiye, Iraq, Iran and Syria. A Kurdish intelligence officer in Erbil said this diversity influences internal dynamics.

“Iranian and Syrian recruits tend to focus on their own countries’ issues, unlike the more hardline Turkish and Iraqi cadres,” the officer said.

But a senior PKK official rejected that view. “The PKK’s decisions are made pragmatically,” he said. “They depend on region, country, political context, and the party’s interest. We adapt to where we operate.”

Around Qandil, many describe the range as the capital of a fully formed partisan society—home to partizans, a term used for members of resistance and guerrilla movements.

‘Mountain law’: Inside the PKK’s Strict Code of Armed Struggle

Qandil has become more than just a stronghold — it is a fortress for partizans governed by the unwritten rules of armed struggle.

“Everything runs according to guerrilla warfare discipline,” said Jabar al-Qadir, a Kurdish researcher from Kirkuk. “Movements like these rely on guerrilla tactics, especially in rugged terrain.”

Former affiliates familiar with life inside Qandil described it as a world ruled by rigid systems — “like living in a real-life version of Squid Game,” one said, requesting anonymity.

“Every mistake has consequences. Every act of betrayal leads to punishment. The solitary cells were rarely empty.”

The PKK’s internal discipline is enforced through what is often referred to as “mountain law,” a strict code that governs behavior, loyalty, and dissent.

In a 2007 interview with Asharq Al-Awsat, Osman Ocalan — brother of the PKK founder— revealed he had been imprisoned for three years within Qandil, including three months in solitary confinement, after proposing reforms to the party’s structure.

Osman was later publicly denounced by PKK military commander Duran Kalkan, a Turkish national, who called him “defeatist” in a statement to the pro-PKK Firat news agency.

Strict regulations govern nearly every aspect of life in the mountains. Romantic relationships, sexual activity, and even marriage are banned. According to the PKK’s internal doctrine, emotional attachment is seen as a distraction from revolutionary struggle and a threat to collective discipline.

“There’s an official manual,” one source said. “Love is treated as a weakness that undermines the cause.”

The Syrian front: Erdal’s Shadow over the Kurdish Fight against ISIS

On the Syrian front, Mazloum Abdi — commander of the US-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) — is widely seen as a protégé of Bahoz Erdal, one of the PKK’s most prominent military leaders.

Abdi, a Syrian Kurd, came under Erdal’s wing in his early twenties, according to a PKK source in Qandil. “He left the PKK and returned to Syria in September 2014, when ISIS began attacking Kurdish towns and villages,” the source said.

But the enduring connection between the two men has fueled speculation — and contradictions — about Erdal’s influence over Kurdish affairs in Syria. Some believe he played a pivotal role in empowering the Democratic Union Party (PYD), the PKK’s Syrian affiliate, since its founding in 2003.

Kurdish activists inside and outside the PKK sphere say Erdal often falls into contradictions when assessing the situation in Syria.

Just five months after Syria’s uprising began in 2011, Erdal declared that “Bashar al-Assad and his supporters have lost all legitimacy.”

That statement came at a time when Syrian Kurds were rising up in force, galvanized by the assassination of prominent Kurdish opposition figure Mashaal Tammo in October 2011.

In the months that followed, forces loyal to Syrian President Bashar al-Assad pulled out of Kurdish towns and villages in the country’s north, leaving a power vacuum.

Stepping in were units affiliated with the PYD, which swiftly moved to establish what it called “administrative entities” — a framework that became the backbone of Kurdish self-rule in Syria.

The PYD, often described as the Syrian sibling of the PKK, is ideologically aligned with Qandil through the umbrella of the KCK, the transnational network that links Kurdish movements in Türkiye, Syria, Iraq and Iran.

A Kurdish intelligence officer familiar with the PKK file says the Assad regime’s withdrawal from Kurdish areas in northern Syria was not a retreat, but part of a tacit deal.

“Handing over those areas to the PYD was a calculated move,” he said. “In return, the party stayed neutral during the Syrian uprising and distanced itself from other Kurdish factions.”

At the start of the 2011 revolution, Syrian Kurds were eager to rise up. Under Assad’s rule, many lived without basic civil rights.

Even simple acts—such as holding a Kurdish wedding with traditional dabkeh dancing—required prior approval from state security. Newborns couldn’t be given Kurdish names; the state would assign Arabic ones instead.

In a previous interview, Erdal claimed he did not return to Syria after the uprising—except briefly in 2014 for “family reasons.” But that year also marked the rise of the People’s Protection Units (YPG), the PYD’s armed wing, which later formed the backbone of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF).

Erdal’s role in Syria has remained deliberately ambiguous. He is believed to have been instrumental in shaping the PKK’s military strategy and establishing its combat units. Some reports even claim he helped form covert armed groups such as the Kurdistan Freedom Hawks (TAK), which carried out suicide car bombings in Türkiye over the past two decades.

A PKK source in Qandil denies any connection. “That theory is impossible,” he said. “The Hawks see the PKK as not radical enough to respond to Türkiye’s attacks or to break Ocalan out of prison.”

Ocalan, often referred to as “Apo”—meaning “uncle” in Kurdish and Turkish—remains the symbolic leader of the broader Kurdish movement.

Iran

Iran was not part of the picture when the PKK was founded. It began as a Marxist movement fighting for a “Greater Kurdistan,” then shifted to demands for “autonomy,” and now champions a “democratic confederation.” But its path into the regional equation began not through Tehran, but Damascus.

Following Türkiye’s 1980 military coup led by General Kenan Evren, PKK fighters fled to Syria and Lebanon. There, they quickly became part of the region’s anti-imperialist bloc. Ironically, PKK founder Ocalan lived in the same apartment building as Türkiye’s military attaché in Damascus, according to late Syrian Vice President Abdel Halim Khaddam, who told a Turkish TV station in 2011: “No one would have imagined he was living there.”

The PKK’s early ties to Iran were not direct but routed through Hafez al-Assad’s Syria, which hosted Ocalan and allowed the group to run training camps near Lebanon’s Beqaa Valley.

In 1992, a year after Iraq’s Kurds rose up against Saddam Hussein, the United States and its allies enforced the so-called “Line 36” no-fly zone to protect Kurdish areas in northern Iraq. But tensions among the Kurds themselves remained.

The two main Kurdish parties in Iraq—the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) led by Jalal Talabani and the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) headed by Masoud Barzani—joined forces to fight the PKK in the Qandil mountains. “Some 2,000 PKK fighters surrendered,” said Qaradaghi.

“They were brought down from the mountains and Talabani sent them to Zaleh,” a region in western Iran near the Iraqi-Kurdish border.

Sensing an opportunity, Iran moved quickly. The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) offered the wounded fighters food, medicine, and training. Once recovered, Qaradaghi said, they were routed back to Qandil through a path that looped around the Turkish-Iraqi-Iranian triangle—back to the same mountains Talabani had emptied.

But Iranian support came with strings attached. Tehran expected the PKK’s Iranian offshoot, PJAK, to refrain from carrying out attacks inside Iran.

Was Talabani wrong to choose Zaleh as a haven for the defeated PKK fighters? Qaradaghi argues the late president’s decision was strategic. Talabani had initially planned to house them in a heavily fortified military base between Sulaymaniyah and Dukan, “but he feared Turkish airstrikes. So he opted for Zaleh,” which Turkish jets would avoid striking for fear of violating Iranian airspace.

PKK and Iran: A Shadowy Alliance

The PKK’s relationship with Iran is cloaked in secrecy, shaped by an intricate web of people, places and overlapping interests. Over the years, Turkish and Kurdish media outlets such as Darka Mazi—meaning “Path of Hope” in Kurdish—have circulated claims that Tehran struck a deal with the PKK as early as 1986.

Independent journalistic sources told Asharq Al-Awsat that no formal agreement exists, but rather a series of tactical understandings over the years, benefiting both sides.

For Iran, the PKK represents a double-edged sword: a destabilizing nationalist movement with potential to stir unrest among Iran’s own Kurdish population, yet also a strategic buffer against Turkish ambitions in the tri-border region linking Iran, Iraq and Türkiye.

“There’s no written agreement,” said Kurdish analyst Jabbar Qadir. “But the two sides share positions that have led to a kind of quiet coordination.” Iran, he added, has offered logistical concessions that avoid provoking Ankara, while the PKK has largely refrained from causing trouble on Iranian soil—even though it established an Iranian offshoot, PJAK, whose mandate includes countering the influence of the Kurdish Democratic Party of Iran.

Qadir situates the PKK’s role within what is now referred to as the “Axis of Resistance,” a term Iran uses to describe its regional alliance. Still, he insists the group has not become an Iranian proxy. “The PKK has its own financial means and procures its weapons independently. It’s not reliant on Iranian funding like Tehran’s other militias.”

Tensions flared in 2010 and 2011 when PJAK stepped up its attacks on Iranian forces, prompting heavy retaliation. But the eruption of Syria’s civil war in 2011 created new priorities. Both sides needed to conserve strength and focus on their respective agendas in Syria, leading to a quiet de-escalation pact.

By late 2015, the PKK’s standing within the Axis of Resistance had shifted dramatically amid the battles against ISIS. A senior Shi’ite commander in an Iran-backed faction said Iranian officials were struck by the PKK’s discipline and combat effectiveness.

“They viewed the PKK fighters as more organized, committed and fierce than others—almost on par with Hezbollah,” he said. “Their fierce battles to liberate Sinjar from ISIS even impressed the US-led coalition, which began coordinating with them.”

As ISIS spread deeper into Iraq, Qassem Soleimani—the powerful IRGC commander—coordinated PKK operations within a broad network of militias stretching from Iraq’s Popular Mobilisation Forces to Hezbollah in Lebanon. Kurdish fighters were deployed along critical supply corridors linking Iran to Lebanon’s Beqaa Valley.

The most sensitive stretch lies along the horizontal axis between Qandil, Sinjar and northeastern Syria. Sources familiar with the matter say the PKK capitalised on its central role in Sinjar’s liberation and its alliance with local Yazidi groups. Together, they formed an armed force known as the Sinjar Protection Units, or YBS.

The Final Act: How Ocalan’s Vision Shifted After Decades in Isolation

Few expected it. When the PKK announced its 12th Congress would be held on May 5–7, 2025, it marked a stunning departure from the group’s long-standing secrecy. What would once have been a covert meeting of a handful of cadres turned into a historic public gathering of hundreds of party leaders.

“The world is changing, and the PKK had to listen—even if reluctantly,” said Deniz Caner, a Turkish researcher close to the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP).

But how did Ocalan, the party’s jailed leader, arrive at this moment—more than four decades after launching an armed struggle? Qadir, who met Ocalan in Damascus in the mid-1990s “at the height of his leadership,” believes that over 25 years in prison forced a deep rethinking. “He came to see his party’s model as rooted in Cold War logic,” Qadir said, referencing Öcalan’s latest message to supporters.

Caner, who has closely tracked the group’s ideological evolution, described the PKK’s transformation as cyclical: “The party sheds its skin every 20 years. It has already undergone two major transitions, and this is the third—shaped by the Iran-Iraq war, the fall of Saddam Hussein, the rise of Iraqi Kurdistan, the Arab Spring, the emergence of ISIS, and the Syrian revolution.”

Shwan Taha, a former Kurdish MP and academic who served in Iraq’s federal parliament from 2006 to 2010, said Ocalan’s change of heart also reflected shifts in modern warfare. “He came to realize that the mountains of Qandil stand no chance in an age of technological warfare,” he said. Taha added that Ocalan was also likely influenced by the Beirut suburb “Pager Operation,” after which Hezbollah chief Hassan Nasrallah was assassinated.

“Dissolving the party,” Taha said, “could ultimately save the Kurds from disappearing forever.”

Other factors also played a role in Ocalan’s apparent pivot. According to Qaradaghi, two key developments shaped his decision: “First, the deep isolation of his detention in İmralı prison. And second, that this peace overture came not from Erdogan, as in the past, but from Devlet Bahceli”—leader of Türkiye’s far-right Nationalist Movement Party.

It appears Ocalan is not the only one undergoing a shift—or being compelled to. On the other side, Erdogan may also need a new dynamic to secure a constitutional change that would allow him to seek a third presidential term. That would require forging broader, more agile alliances—an unlikely feat without a sweeping, multi-party deal.

Such a deal would need to satisfy nationalists seeking cultural and economic reforms, and Kurds demanding a greater political role—many of whom increasingly lean toward opposition parties.

Still, Caner disagrees with the theory that Erdogan is simply maneuvering for internal gains. “Erdogan isn’t chasing victory just to offset domestic crises,” she said.

Lowering the Qandil Flag

PKK officials have offered shifting explanations for their disarmament. Over time, their rhetoric moved from giving up arms to halting war while keeping weapons in reserve—coupled with hardline statements from affiliated parties like Iran’s PJAK.

Yet the greatest operational freedom remains in Syria, where the Kurdish-led SDF is seen by analyst Shwan Taha as “the biggest winner”—the surviving offspring, as he put it, “after the mother was sacrificed.”

From the outset, Qadir predicted that PKK leaders in the Qandil Mountains would prolong the disarmament phase until Türkiye took concrete steps to recognize Kurdish cultural rights.

According to Arsan, Ocalan set clear conditions: constitutional amendments to grant cultural rights, legislation to enable the PKK’s transition into legal politics in Türkiye—and, above all, his own release.

“No fighter will give up their weapon unless those conditions are met,” Arsan said. Some PKK commanders reportedly heard directly from Ocalan that “Erdogan agreed to everything.”

Such hopes, however, may be overly optimistic, says Caner. “Meeting demands like these is unlikely,” she said, adding that “even if a genuine deal emerges, implementation could take years.”

Independent media sources say surprises remain possible. “At most,” one source noted, “Ocalan may be moved to a more suitable house on İmralı Island—under tight security.”

PKK spokesman Zagros Hiwa denied any formal agreement with the Turkish state, written or otherwise. “These are unilateral goodwill gestures aimed at finding a democratic solution to the Kurdish issue,” he said.

The Fate of the Mountain and the Gun

When asked about the future of the Qandil Mountains after a potential PKK withdrawal, Hiwa said: “These historic heights could play a decisive role not just for the Kurdish people, but for the peoples of the Middle East as a whole.”

But Jabbar Qadir warned that both regional governments and the international coalition fear that, if vacated, Qandil could become a haven for extremists. Iran, in particular, “is working to prevent hostile groups from taking root there,” he said.

Ankara, for its part, appears unwilling to jeopardize fragile progress. Iran’s influence in the talks between Ocalan and Erdogan has become largely peripheral.

Caner estimated that about 30% of the PKK’s positions in Qandil lie within Iranian territory, where several of the group’s top leaders are based. Resolving this sensitive piece of the puzzle may require “military intervention inside Iran with US and Israeli backing—an unpredictable scenario,” she said.

At the individual level, options include reintegrating fighters into their home countries—Türkiye, Iraq, Syria, and Iran—or relocating them to a European country willing to take them in. In Türkiye, however, around 50 senior PKK figures are blacklisted from return and will not be included in any reintegration lists.

Throughout this 40-year story, Ocalan has been both its beginning and end. The man who once scattered clandestine pamphlets in Ankara and Istanbul in the mid-1970s—while envisioning a “Greater Kurdistan”—is now scripting the closing act for Qandil.

Asked what the PKK stands to gain from peace, sources repeatedly answered: “The Kurdish fighter is simply tired of war.” But none of this might have happened had Ocalan not decided to lay down the mountain’s guns and embrace the kind of pragmatism he long mastered.

In a final message to this investigation, spokesman Hiwa sounded far from optimistic: “Türkiye will not change its mindset toward the Kurds, and it has done nothing that matches Ocalan’s initiative.”

Hiwa’s tone echoed the bitter history of failed ceasefires and aborted reconciliations. Yet Qaradaghi still hopes to one day return to the seven peaks he visited half a century ago—this time as a tourist.

Others fear they may never hear another word from Ocalan again—his voice silenced on an island in the Sea of Marmara, whose waves have long kept the secrets and sorrows of the Turkish people.