An Israeli strike on a meeting of Hamas officials in Qatar has cast a cloud of growing concern across Türkiye that it could be the next target.

Turkish Defense Ministry spokesman Rear Adm. Zeki Akturk warned in Ankara on Thursday that Israel would “further expand its reckless attacks, as it did in Qatar, and drag the entire region, including its own country, into disaster.”

Israel and Türkiye were once strong regional partners, but ties between the countries ran into difficulties from the late 2000s and have reached an all-time low over the war in Gaza sparked by the Oct. 7, 2023, Hamas-led attack in southern Israel. Tensions also have risen as the two countries have competed for influence in neighboring Syria since the fall of Bashar al-Assad’s government last year.

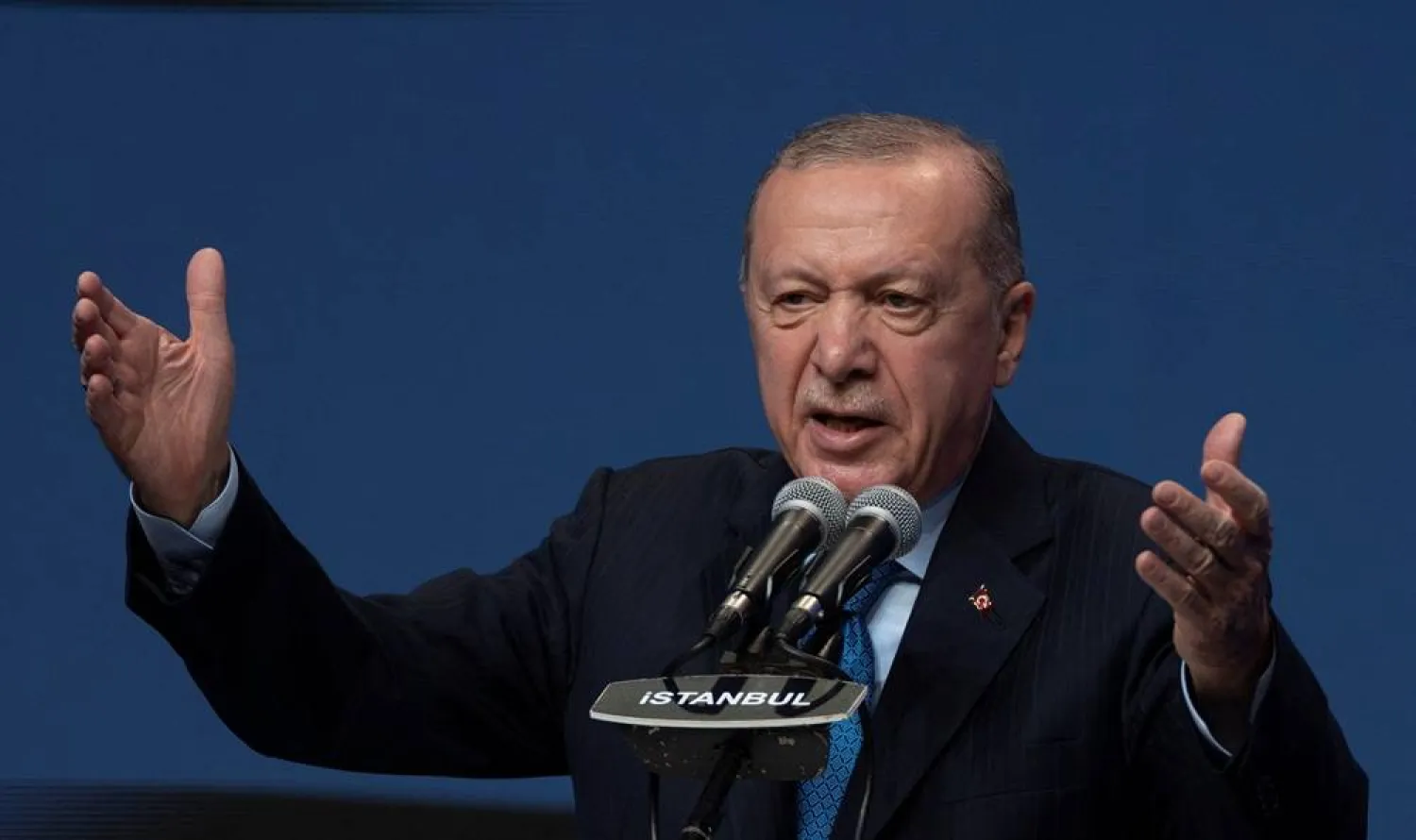

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has been a long-standing supporter of the Palestinian cause and of the Palestinian group Hamas. The Turkish president has criticized Israel, and particularly Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, with strident rhetoric since the start of the Gaza war, accusing Israel of genocide and likening Netanyahu to Nazi leader Adolf Hitler.

Hamas officials regularly visit Türkiye and some have taken up residence there. Israel previously accused Türkiye of allowing Hamas to plan attacks from its territory, as well as carrying out recruitment and fundraising.

After Israel’s attacks on the territory of Iran, Syria, Yemen and now Qatar, Ankara is bound to be concerned by Israel’s ability to freely use the airspace of neighboring states.

“Israel’s ability to conduct strikes with seeming impunity, often bypassing regional air defenses and international norms, sets a precedent that deeply worries Ankara,” said Serhat Suha Cubukcuoglu, director of Trends Research and Advisory’s Türkiye program.

Türkiye sees these attacks as a “broader Israeli strategy to establish a fragmented buffer zone of weak or pacified states around it,” he added.

Türkiye has superior military might In crossing a previously unthinkable line by attacking Qatar, a close American ally that has been serving as a mediator in Gaza ceasefire talks, Israel also has raised the question of how far it will go in pursuing Hamas targets.

Through its NATO membership, Türkiye would seem to have a greater degree of protection against Israeli attack.

Türkiye also boasts significantly greater military might, with its armed forces second in size only to the US among NATO countries and an advanced defense industry.

As tensions rise, Türkiye has boosted its defenses. During Israel’s attacks on Iran’s nuclear facilities in June, Erdogan announced an increase in missile production. Last month he formally inaugurated Türkiye’s “Steel Dome” integrated air defense system, while projects such as the KAAN fifth-generation fighter have been fast-tracked.

Ozgur Unluhisarcikli, director of the German Marshall Fund in Ankara, said an Israeli airstrike on the territory of a NATO member would be “extremely unlikely,” but small-scale bomb or gun attacks on potential Hamas targets in Türkiye by Israeli agents could be a distinct possibility.

Cubukcuoglu, meanwhile, said the Qatar attack could harden Ankara’s support for Hamas.

“This resonates with Turkish anxieties that Israel may eventually extend such operations to Turkish territory,” he said. “The Turkish government calculates that abandoning Hamas now would weaken its regional influence, while standing firm bolsters its role as a defender of Palestinian causes against Israeli aggression.”

Tensions could play out in Syria While attention is focused on tensions surrounding the war in Gaza and Türkiye’s relations with Hamas, Unluhisarcikli warned the greater danger may be in Syria, where he described Israel and Türkiye as being “on a collision course.”

“To think that targeting Turkish troops or Turkish allies or proxies in Syria would be to go too far is wishful thinking,” he said.

Since Syrian opposition factions unseated Assad in December, rising tensions between Türkiye and Israel have played out there. Ankara has supported the new interim government and sought to expand its influence, including in the military sphere.

Israel views the new government with suspicion. It has seized a UN-patrolled buffer zone in southern Syria, launched hundreds of airstrikes on Syrian military facilities and positioned itself as the protector of the Druze religious minority against the authorities in Damascus.

Tensions also could spill into the wider eastern Mediterranean, with Israel potentially drawing closer to Greece and Greek Cypriots to challenge Türkiye’s military presence in northern Cyprus.

Türkiye mixes deterrence and diplomacy Türkiye appears to be pursuing a mixture of military deterrence and diplomacy in Syria aimed at defusing tensions to avoid a direct conflict with Israel.

Turkish and Israeli officials held talks in April to establish a “de-escalation mechanism” in Syria. The move followed Israeli strikes on a Syrian airbase that Türkiye had been purportedly planning to use. Netanyahu said at the time that Turkish bases in Syria would be a “danger to Israel.”

Ankara and Damascus last month signed an agreement on Türkiye providing military training and advice to Syria’s armed forces.

Erdogan also may hope Washington would take a hard line against any Israeli military incursions.

While Netanyahu has sought support from US President Donald Trump in the faceoff with Türkiye, Trump instead lavished praise on Erdogan for “taking over Syria” and urged Netanyahu to be “reasonable” in his dealings with Turkey.

But as the strike in Qatar showed, having strong relations with Washington is not necessarily a safeguard against Israel.

The Qatar attack showed there was “no limit to what the Israeli government can do,” Unluhisarcikli said.