In May, Syrian tycoon Rami Makhlouf, a cousin and long-time ally of president Bashar Assad, took a once unimaginable step.

In a video he published on social media, he lashed out against Assad’s “inhumane” state security forces. “Mr. President, the security forces have started attacking people’s freedoms,” Makhlouf said.

The outburst shocked Syrians, and exposed a rift at the heart of the ruling elite. Never before had such a senior figure spoken out against the regime from within Damascus.

Through Syria’s 10-year war, Makhlouf had helped Assad evade Western sanctions on fuel and other goods vital to his military campaign. He was part of the president’s inner circle, accused by the United States of exploiting his proximity to power to enrich himself “at the expense of ordinary Syrians.” His business empire spanned telecoms, energy, real estate and hotels, looming large over Syria’s economy.

But now the two men were locked in a battle over money. Security forces had recently raided Makhlouf’s telecoms company, Syriatel, in a tax dispute and detained dozens of employees for questioning.

Makhlouf’s public defiance showed that a threat to Assad’s iron rule may ultimately come, not from the battlefield, but from once loyal allies and Syria’s collapsing economy. In a nation where criticism of the ruler is rarely tolerated, Makhlouf has been able to speak out, people familiar with the matter say, because of the family connection and because he is well regarded in the Alawite Muslim community that dominates the top echelons of Syria’s leadership. Makhlouf and Assad are both Alawite.

Reuters spoke to more than 30 sources - including people close to the Assad and Makhlouf families, local businessmen, and Western intelligence officials - and reviewed official documents to chart the breakdown of a family alliance that stretched back two generations. Many of the sources declined to be named because of the sensitivity of the matter.

In interviews, these sources described how:

• In expanding his business empire over two decades, Makhlouf kept some of his wealth hidden from the president.

• In May 2019, Assad instructed Syria’s intelligence chief to track down Makhlouf’s estimated billions of dollars of riches stashed abroad.

• After a decade of war, Assad is so desperate for cash that in September 2019 the central bank summoned Syrian tycoons to a meeting and ordered them to hand over some of their fortunes.

“Makhlouf has brought into the open the feud within the regime,” said a person with ties to the Assad family.

The Syrian Information Ministry didn’t respond to detailed questions for this story. Questions emailed to Makhlouf via his son went unanswered. Syriatel didn’t comment.

The rise

The financial arrangement between the Assad and Makhlouf families began with the fathers.

Assad’s father, Hafez, an air force officer from a mountain village, seized power in a military coup in 1970. He turned to Makhlouf’s father, Mohamed, to manage the money, derived from state-controlled industries and contract commissions, that would shore up his rule. Mohamed, known as Abu Rami, had financial skills that Hafez lacked.

“The Makhlouf side was generally better educated and refined, so they could help out with the finances, which is something the Assads were not good at and didn’t have the education for,” said Joshua Landis, a Syria specialist and head of the Center for Middle East Studies at the University of Oklahoma. “They were also better at dealing with the people of Damascus and Aleppo, who dominate Syria’s economy.”

Makhlouf senior reaped extensive rewards from the relationship. In the 1970s, he was appointed head of the General Organization of Tobacco, which had a monopoly over the industry in Syria. A decade later he expanded his business interests as chief of the state-owned Real Estate Bank, and acted as middleman for government contracts.

The sons grew up together and were close. As a young man, Rami Makhlouf “used to go to Assad’s residence and open the fridge like any family member,” said a former business associate of Makhlouf.

Ayman Abdel Nour met both men at Damascus University in the 1980s when he was a teaching assistant and they were students. Abdel Nour now lives in the United States. Makhlouf and Assad were so close that even their mannerisms were similar, Abdel Nour said. “Rami would sit very calmly, in a way that was similar to Bashar. He copied his personality because they grew up together.”

Bashar’s mother, Anisa, was Rami’s aunt. With a strong personality and deep political influence, she lobbied for her nephew within the family and was instrumental in his rise, said people who know the family. As his father aged, Rami smoothly took over the responsibilities as money manager for the Assads.

In the early 2000s Syria enjoyed rapid economic growth and Makhlouf’s business flourished. The jewel in the crown was telecoms firm Syriatel. The company has grown from a few hundred thousand subscribers in the early 2000s to around 11 million, according to Makhlouf. “Rami built Syriatel into a sophisticated business that many of Syria’s best and brightest wanted to work for,” said Landis.

Makhlouf drew the attention of the United States. In 2008, the US Treasury imposed sanctions on the tycoon, describing him as “one of the primary centers of corruption in Syria.” The Treasury alleged he manipulated the justice system and used state intelligence officials to intimidate rivals and acquire exclusive licenses to represent foreign firms in Syria. His ties to Assad brought him lucrative oil exploration and power plant projects, the Treasury said.

“Rami Makhlouf has used intimidation and his close ties to the Assad regime to obtain improper business advantages at the expense of ordinary Syrians,” Stuart Levey, then Under Secretary for Terrorism and Financial Intelligence, said at the time.

Makhlouf, who rarely spoke in public, didn’t respond to the sanctions.

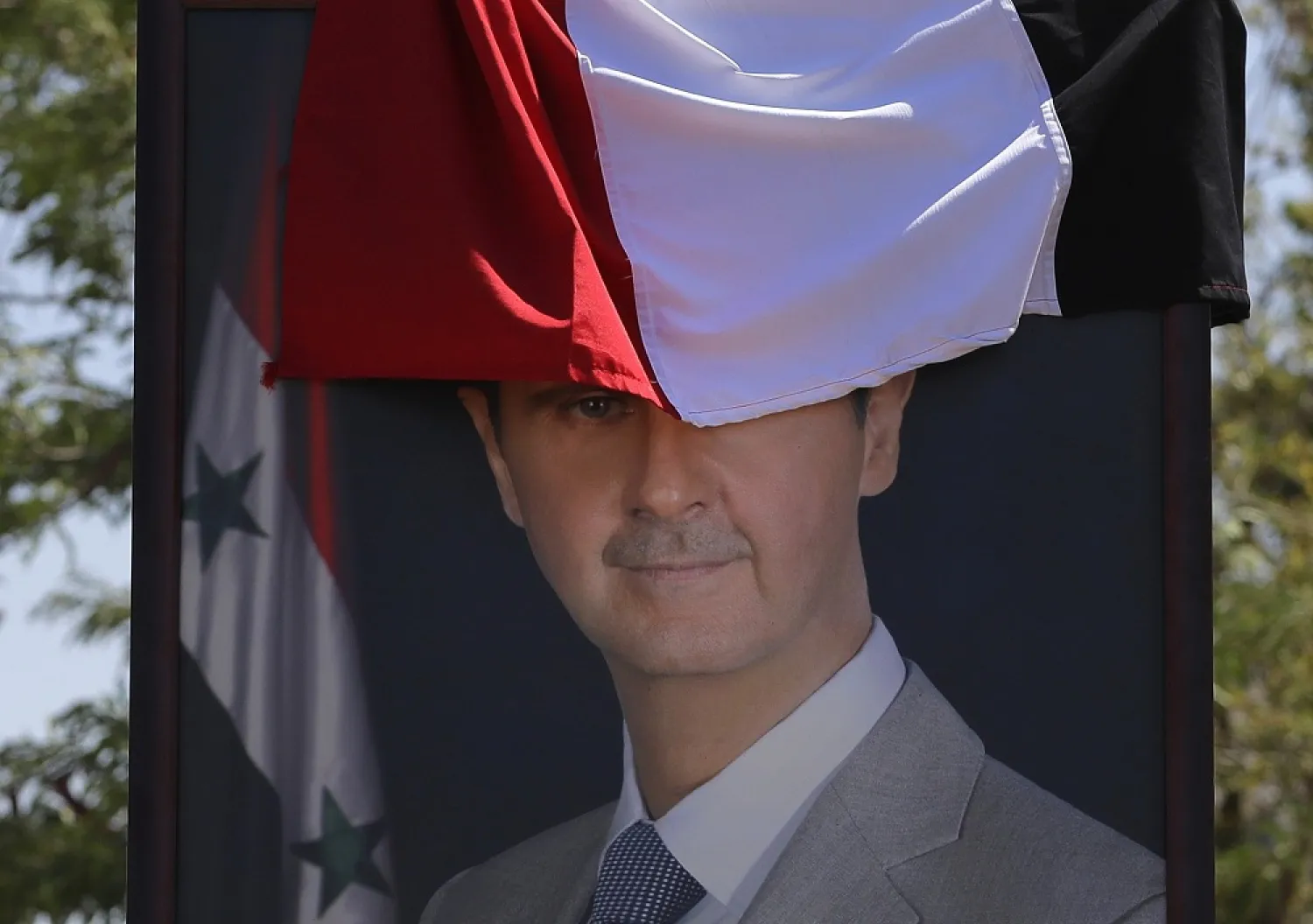

When protesters took to the streets calling for Assad’s overthrow in 2011, their chants were also directed against “the thief” Makhlouf. As the popular uprising turned into a civil war and then a multifaceted conflict, Makhlouf helped power Assad’s military campaign with fuel and other imports.

Behind Assad’s back, he was also feathering his own nest, said more than a dozen sources with knowledge of the matter. A former business associate and a banker said Makhlouf had created a network of front companies, including in neighboring Lebanon, where he generated his own money separate from the funds Assad asked him to place in safe havens on behalf of the ruling family. They didn’t quantify the sums of money involved.

In a post on social media on July 26 of this year, Makhlouf conceded that he set up such firms, but insisted “these companies’ role and aim is to circumvent sanctions,” not to enrich himself.

Among Makhlouf’s interests outside Syria was a Beirut law practice called Middle East Law Firm SAL. Publicly available data show the firm was set up in 2001 by Makhlouf, his brother and Lebanese partners. According to Lebanon’s Commercial Register, the law firm continues to operate and its activities include the management of companies inside and outside Lebanon and foreign trade transactions. Reuters couldn’t reach the law firm or its partners for comment, nor could the agency determine whether Makhlouf plays any role there today.

One former business associate with first-hand knowledge said that Makhlouf set up entities in Jersey and the Virgin Islands. “Makhlouf would buy supplies and equipment for the government from companies that he ultimately owns. He would create these shell companies that would be suppliers,” said the former associate, a shareholder in Makhlouf’s Cham Holding, a real estate developer.

Makhlouf’s personal wealth has been estimated by Syrian business associates at between $5 billion and $15 billion. Its true scale is a closely held secret. In one of his recent video appearances, Makhlouf said profits from his businesses were used for charitable causes, such as funding injured war veterans and bereaved families, via a holding company he owns.

The fall

With the help of Russia and Iran, Assad has turned the tide of Syria’s war. But victory on the battlefield has come at a cost.

Syria’s economy is in ruins. The Syrian pound has lost almost 80% of its value over a decade of war. The fighting has caused tens of billions of dollars’ worth of damage, disrupted agriculture, devastated industry and wiped out foreign currency flows from tourism and oil exports. Inflation is rampant and many Syrians are struggling to afford even basics such as food and power. Eight in 10 people live below the poverty line in Syria, according to the United Nations.

While Russia has backed Assad militarily and with food supplies, its intervention isn’t for free. Syria has to pay for much of the Russian wheat it imports and for weaponry.

In recent months, a banking crisis in neighboring Lebanon has cut off a vital source of dollars for the regime, worsening the economic shock and aggravating already strained money relations between Assad and Makhlouf.

While much of Syria lies in ruin, two of Makhlouf’s sons have been living lives of luxury. On social media, they posted pictures, many since deleted, of fancy sports cars, a private jet and opulent homes.

In one video, in the summer of 2019, Mohamed Makhlouf, one of Rami’s sons, appeared driving a Ferrari in the South of France. The camera zoomed in on the speedometer as he revved the engine. Another video showed him at a beach party on the Greek island of Mykonos. Someone commented beneath the post: “It’s been 45 years and they are still stealing from the people.”

As the economy imploded, Assad became determined to bring home the billions of dollars held by Makhlouf in offshore companies, said more than a dozen sources. These sources include well-connected people in Syria’s financial community, an official with ties to Assad’s government and Western intelligence sources.

In the summer of 2019, Assad and his brother Maher, head of the Republican Guard that defends Assad’s seat of power in Damascus, met with Ali Mamlouk, the head of Syria’s intelligence agency, the General Intelligence Directorate. At that meeting, the Assads told Mamlouk to track down Makhlouf’s wealth overseas, said a person allied with the Syrian government and a Western intelligence source who was briefed about the meeting. Reuters couldn’t independently verify this account. Syrian authorities didn’t respond to questions about the matter.

“It was time to put the house in order” now that the security pressures on the regime had eased after containing the insurgency, said the Western intelligence source.

A first sign of Makhlouf’s fall from grace came in December 2019, when Syria’s customs directorate accused Makhlouf and some other businessmen of importing goods without declaring their real value. The order, which was reviewed by Reuters, froze the assets of Makhlouf and his wife. It was signed by Syria’s finance minister. Makhlouf has since said he paid seven billion Syrian pounds ($3 million) to settle the dispute. Syrian authorities didn’t comment.

The sums accumulated abroad by Makhlouf - estimated in excess of $10 billion by members of Syria’s business community - are of real economic consequence. One Western diplomat said repatriating the money “is of existential importance for the regime.”

Though he caved in the customs dispute, Makhlouf has resisted surrendering his vast holdings. He told the president to seek dollars elsewhere, from other tycoons, said bankers and business associates familiar with the matter.

Starting early this year, Syrian security forces began a campaign of arrests that netted dozens of employees at Makhlouf’s Syriatel, without legal explanation. Sources in Syria said people were arrested, sometimes released and then re-arrested. Reuters couldn’t determine whether any charges have been brought. A Damascus banker with knowledge of the matter said the employees were questioned about fund transfers to front companies set up by Makhlouf in the British Virgin Islands and Jersey.

“They were interrogating them over the details of offshore companies that have signed management deals with Syriatel,” said the Damascus banker. He did not elaborate, and Reuters couldn’t determine whether any money had been repatriated.

A businessman said the detentions were designed to send a message to those working for Makhlouf “that he is in disgrace.”

The rift between Assad and Makhlouf burst into public view on April 30, when Makhlouf posted the first of three videos to social media. In the videos, he said the government had asked him to step down from his companies, including Syriatel. He also spoke of threats by unspecified people in the regime to revoke Syriatel’s license and seize its assets if he did not comply.

On May 19, 2020, the finance ministry froze the assets of Makhlouf, his wife and an unspecified number of his at least two children, according to a document reviewed by Reuters. It also ordered that overseas assets should be seized “to guarantee payment of dues to the telecom regulatory authority.” The government has said Syriatel owes the telecom regulator 134 billion Syrian pounds ($60 million) relating to the terms of the company’s license. Makhlouf insisted in one of his social media posts that he stands ready to pay.

A separate order banned Makhlouf from obtaining government contracts for five years.

A former business associate said years of acting as Assad’s trusted money keeper and family treasurer made Makhlouf feel like a partner. “Makhlouf was telling his cousins (the Assads), ‘we are partners,’ and it has shocked him they are now telling him, ‘no you are not, you are just serving us’,” said the associate, who used to work with Makhlouf.

Hunt for cash

As Makhlouf has fallen, others have stepped into his place.

One powerful man who has emerged at the top of a new elite is Samer Foz, a building contractor turned commodities trader. Foz, a Sunni Muslim, was sanctioned by the United States in June 2019, along with more than a dozen individuals and companies, for providing financial support to Assad.

“Samer Foz, his relatives, and his business empire have leveraged the atrocities of the Syrian conflict into a profit-generating enterprise,” then Undersecretary for Terrorism and Financial Intelligence Sigal Mandelker, said in a statement. “This Syrian oligarch is directly supporting the murderous Assad regime and building luxury developments on land stolen from those fleeing his brutality.”

Foz didn’t comment for this article, telling Reuters: “You can write what you want. I have nothing to say to the press.”

In September 2019, central bank governor Hazem Karfoul assembled some of Syria’s wealthiest players for a closed-door meeting at the Damascus Sheraton. Syrian media have previously reported that the meeting took place, but details of what was discussed are revealed here for the first time.

On the surface, the gathering was projected to the public as an effort to strengthen the struggling currency through donations from Syria’s wealthy elite. But the meeting was not about charity, said three sources briefed by people who attended.

The central bank governor listed the businessmen’s properties and other assets, and the lucrative deals they had struck. He suggested their fortunes could be seized if they did not give a significant contribution to state coffers.

Foz pledged $10 million, according to the sources. The central bank governor told him that wasn’t enough, to which Foz replied, “consider it a first payment,” one of the sources said. Foz didn’t comment.

“This was to show that these merchants of war were being pressured to do their bit for the country,” said a business executive who is close to some of the attendees and a personal friend of the central bank governor. “Everyone knows who they are and how they made their wealth and who they work for.”

Syria’s central bank didn’t respond to Reuters’ questions about the meeting.

‘We shouldn’t disagree’

In recent months, Makhlouf has been projecting himself as a spiritual man, in an apparent attempt to appeal to members of the faith practiced by the minority Alawite sect. Reuters couldn’t determine how Makhlouf’s messages are being received in the community. People were reluctant to discuss the matter with Reuters by phone.

The Alawites rose to dominate the political system in majority Sunni Syria after controlling the army following a coup that brought the Baath Party to power in 1963. The Alawites’ influence has spread to business, undermining a Sunni merchant establishment that had traditionally dominated commerce.

One of Makhlouf’s social media posts after the rift became public was a prayer asking God to end the injustice against him, written in the Alawite dialect.

Commenting on Makhlouf’s social media posts and his messaging, a financial adviser involved in transactions with him before 2011 said the videos were clearly made to appeal to the loyalist Alawite camp.

“He is telling Bashar, ‘We are defenders of our community, we should not disagree.’”

In a recent post, on July 9, Makhlouf remained defiant. Arrests of his employees, he said, hadn’t stopped. “Now it’s only our women who are left,” he said. “Even so, they didn’t get what they wanted to force us to surrender.”