There was no mistaking the reek of death that rose along the Syrian desert highway four nights a week for nearly two years. It was the smell of thousands of bodies being trucked from one mass grave to another, secret location.

Drivers were forbidden to leave their cabs. Mechanics and bulldozer operators were sworn to silence and knew they’d pay with their lives for speaking out. Orders for “Operation Move Earth” were verbal only. The transfer was orchestrated by one Syrian colonel, who would ultimately spend nearly a decade burying Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s dead.

The order for the transfer came from the presidential palace. The colonel, known as Assad’s “master of cleansing,” directed the operation from 2019 to 2021.

The first grave, in the Damascus-area town of Qutayfah, contained trenches filled with the remains of people who died in prison, under interrogation or during battle. That mass grave’s existence had been exposed by human rights activists during the civil war and was long considered one of Syria’s largest.

But a Reuters investigation has found that the Assad government secretly excavated the Qutayfah site and trucked its thousands of bodies to a new site on a military installation more than an hour away, in the Dhumair desert.

In an exclusive report published Tuesday, Reuters revealed the clandestine reburial scheme and the existence of the second mass grave. Reuters can now expose, in forensic detail, how those responsible carried out the conspiracy and kept it a secret for six years.

Reuters spoke to 13 people with direct knowledge of the two-year effort to move the bodies and analyzed more than 500 satellite images of both mass graves taken over more than a decade that showed not just the Qutayfah grave’s creation but also how, as its burial trenches were re-opened and excavated, the secret new site expanded until it covered a vast stretch of desert.

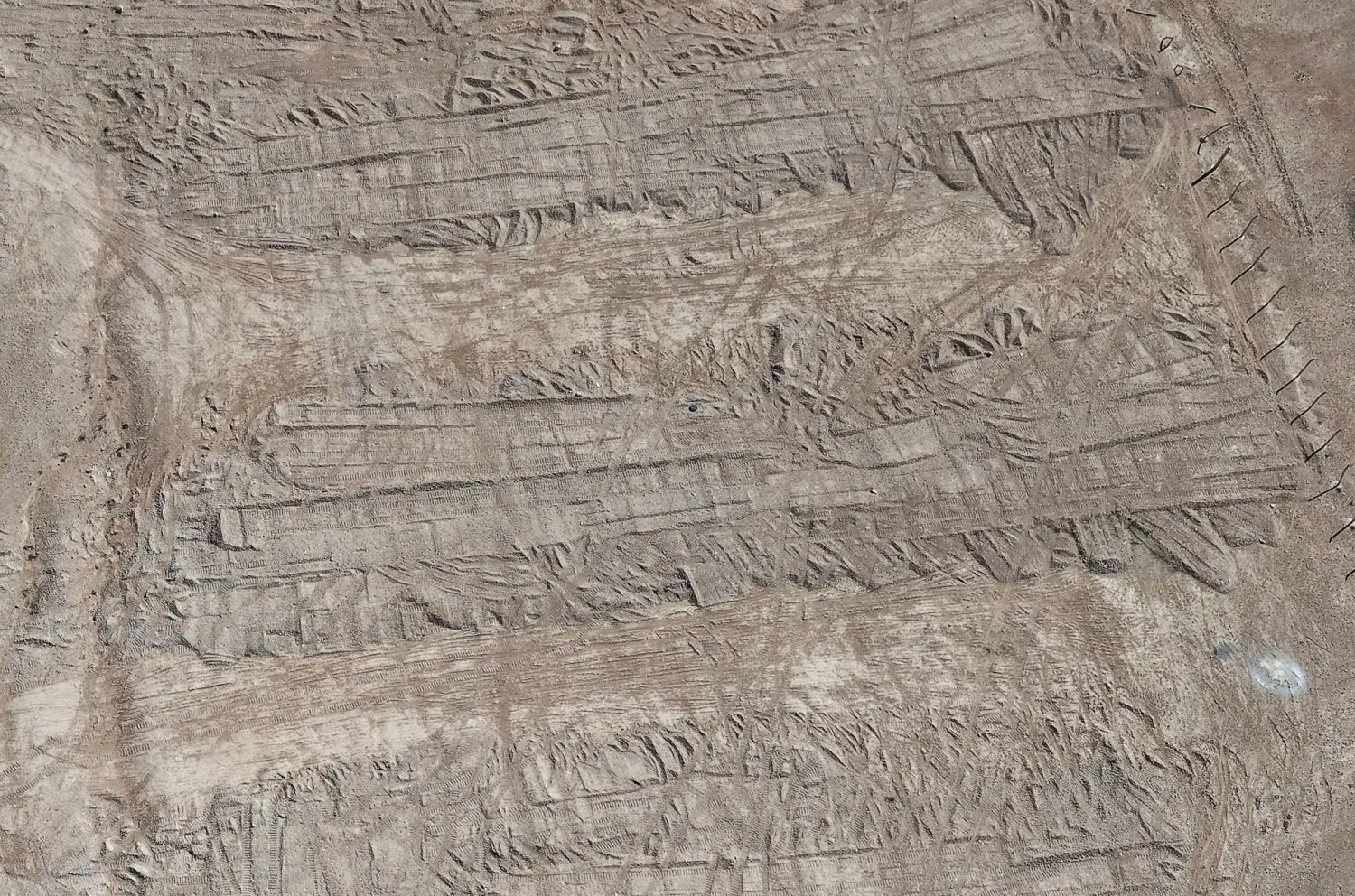

Reuters used aerial drone photography to further corroborate the transfer of bodies. Under the guidance of forensic geologists, the news agency also took thousands of drone and ground photos of the two sites to create high-resolution composite images. At Dhumair, the drone flights showed the disturbed soil around the burial trenches was darker and redder than nearby undisturbed areas – the kind of change that would be expected if Qutayfah’s subsoil were added to the soil at Dhumair, according to Lorna Dawson and Benjamin Rocke, the geologists who advised Reuters.

Syria is dotted with mass graves, but the secret site that Reuters discovered is among the largest known. With at least 34 trenches totaling 2 kilometers long, the grave near the desert town of Dhumair is among the most extensive created during the country’s civil war. Witness accounts and the dimensions of the new site suggest that tens of thousands of people could be buried there.

To reduce the chance that intruders may tamper with the site before it can be protected, Reuters is not revealing its location.

After the initial story by Reuters, the government’s new National Commission for Missing Persons said it had asked the Interior Ministry to seal and protect the Dhumair site. The commission told Reuters the haphazard transfer of bodies to Dhumair would make the process of identifying victims more difficult.

“Each family of a missing person faces particular suffering intertwined with scientific complexities that could turn the identification process into a lengthy and costly technical project,” the commission said.

For four nights nearly every week, six to eight trucks filled with dirt, human remains and maggots traveled to the Dhumair desert site, according to the witnesses involved in the operation. The stench clung to the clothes and hair of everyone involved, according to descriptions from witnesses, including two truckers, three mechanics, a bulldozer operator and a former officer from Assad’s elite Republican Guard who was involved from the earliest days of the transfer.

The idea to move thousands of bodies came into being in late 2018, when Assad was verging on victory in Syria’s civil war, said the former Republican Guard officer. The dictator was hoping to regain international recognition after being sidelined by years of sanctions and allegations of brutality, the officer said.

At the time, Assad had already been accused of detaining Syrians by the thousands. But no independent Syrian groups or international organizations had access to the prisons or the mass graves.

At a 2018 meeting with Russian intelligence, Assad was assured that allies were actively working to end his isolation, the officer said. The Russians advised the dictator to hide evidence of widespread human rights violations. “Most notably arrests, mass graves, and chemical attacks,” he said.

Two truckers and the officer told Reuters they were told the point of the transfer was to clear out the Qutayfah mass grave and hide evidence of mass killings.

Qutayfah’s first trench appeared on satellite imagery in 2012. A Syrian human rights activist exposed Qutayfah by releasing photos to local media in 2014, revealing the existence of the grave and its general location on the outskirts of Damascus, and accused Assad of using the site to conceal the sheer volume of people killed under his leadership. Its precise location came to light a few years later, in court testimony and other media reports.

By the time Assad fell, however, all 16 trenches documented by Reuters had been emptied.

Russia’s foreign intelligence service declined to comment, and a legal advisor for Assad did not respond to requests for comment on Reuters’ findings.

More than 160,000 people disappeared into the deposed dictator’s vast security apparatus and are believed to be buried in the dozens of mass graves he created, according to Syrian rights groups.

The government has estimated the missing since the Assad family’s rule began in 1970 at up to 300,000.

Organized excavation and DNA analysis could help trace what happened to them, easing one of Syria’s most painful faultlines.

But with few resources in Syria, even well-known mass graves are largely unprotected and unexcavated. And the country’s new leaders, who overthrew Assad in December, have released no documentation for any of them, despite repeated calls from the families of the missing.

The National Commission for Missing People said that’s because many records have disappeared or been destroyed, and the gaps in data are immense even for well-known sites like Qutayfah.

There are plans to create a DNA bank and a centralized digital platform for families of the missing, but not enough specialists in forensic medicine and DNA testing, they said.

Reuters reviewed court testimony and dozens of signed documents showing the chain of command from prison deathbeds to morgues. Many of those documents bore the official stamp of the same colonel who oversaw the two mass burial sites: Col. Mazen Ismandar.

All those interviewed who were involved in the transfer of bodies recalled nights working for Ismandar.

Ahmed Ghazal, a mechanic, described nighttime repairs throughout that period in which soldiers ordered him to clear out his garage so the trucks could be fixed quickly and out of sight. Ghazal told Reuters he didn’t believe their initial explanation, that the smell of rot came from chemicals and expired medicine.

He saw the bodies for the first time when he jumped inside the truck bed during a repair job. Then, after a decaying human hand fell on one of his apprentices, Ghazal said curiosity got the better of him and he approached one of the military drivers to ask where the bodies were from. That driver told him they were from Qutayfah, and that the orders were to move them before Syria could open itself to international scrutiny.

Ghazal, who led Reuters to the Dhumair site, described the events he’d witnessed there in a methodical, deep voice. But he said he never spoke out at the time.

To talk, he said, “means death. Just by talking, what happened to the people who are buried here might happen to you.”

Reuters spoke to the driver as well, who recalled his conversation with Ghazal and said Col. Ismandar warned they’d pay if anyone spoke of what they’d seen.

Contacted through intermediaries, Ismandar declined to comment on Reuters’ findings.

“If I’d been able to act freely, I wouldn’t have taken this job. I am a servant to the orders, a slave to the orders,” the driver said. “I was overwhelmed with feelings of fear, the terrible smell and a sense of guilt.”

When he would return home at sunrise, he said, he doused himself with cologne.

“THE MASTER OF CLEANSING”

As an opposition movement against Assad’s rule deteriorated into civil war in 2012, the town of Qutayfah, on the outskirts of Damascus, was one of the few places firmly under government control. So it was to a military site there that people brought the bodies they found during the early days of fighting and Assad’s furious efforts to contain the uprising, said Anwar Haj Khalil, the former head of the city council.

By 2013, truckloads of bodies were arriving from hospitals, detention centers and battlefields. There were so many corpses that two government-owned food distributors – meatpackers and another company that distributed fruit and vegetables – redirected their refrigerated trucks to haul the dead to Qutayfah, according to Haj Khalil and a former brigadier general in the Syrian Army’s 3rd Division, which coordinated burial logistics. The former brigadier general, like many involved in the conspiracy, requested anonymity to describe how it worked.

But no one wanted the responsibility of burying the bodies, said Haj Khalil, who still lives in the area.

They needed a person to oversee the operations and the site. Ismandar began playing that role as early as 2012, according to multiple witnesses and court testimony. He was introduced to the 3rd Division crew as the “master of cleansing operations,” according to the division’s officer.

Ismandar’s actual title, according to documents from 2018 bearing his stamp and reviewed by Reuters, was budget manager for the Syrian military’s Medical Services. That unit was one of the most powerful government bodies, with control over medical care for soldiers and anyone taken to military hospitals, including thousands of prisoners whose deaths were recorded there.

Ismandar and a 3rd Division commander jointly settled upon a communal plot controlled by the military in Qutayfah, Haj Khalil and the brigadier general said.

Initially, bodies came in a few dozen at a time from two nearby hospitals. They had shrouds inked with names, Haj Khalil said. But within a few months, he said, he grew wearily used to calls from Ismandar after midnight to dispose of bodies from the Tishreen Military Hospital outside Damascus. Another officer would call Haj Khalil to dispose of the bodies from the notorious Sednaya Prison.

“Ismandar would tell me, ‘The refrigerator trucks are headed your way. Tell the bulldozer to meet us at the site in a half-hour,’” Haj Khalil said.

Initially, all the bodies from Tishreen and Sednaya were blindfolded, their hands bound with plastic strips, according to a bulldozer operator who worked at Qutayfah beginning in 2014. He said those from Tishreen first arrived in body bags, then in nylon bags, and then in no bags at all. Nearly all were naked, said the operator, who recalled his phone ringing at 2 a.m. with orders to start digging.

The early trenches dug by the army were too shallow, and “were partly the reason I was summoned,” the bulldozer operator said. “Given the nature of the soil, which is mixed with gravel and small stones, the odor quickly spread.” Locals complained about the smell and the dogs who were drawn to it, he said.

He said he dug each trench roughly 4 meters deep and wide, and between 75 and 90 meters long. His account corresponds to satellite imagery analyzed by Reuters: The images from 2013 when trench digging began in earnest appear to show shallow trenches, followed by longer and deeper gashes in the earth in 2014.

“I couldn’t sleep or eat for the first two weeks because of the horror of what I saw,” the bulldozer operator told Reuters. “But after that, something inside me snapped and I got used to it.”

All the while, Ismandar maintained a series of logbooks detailing the number of bodies arriving and the security branch that sent them, according to sworn testimony from a gravedigger named Mohammed Afif Naifa in German and US cases involving allegations of torture against the Assad government. Naifa told a German court that he worked with Ismandar from 2011 to 2017 and coordinated the burials of political prisoners. Naifa, whose testimony referred to Qutayfah but didn’t touch upon Dhumair, declined to speak with Reuters.

He testified that the numbers in the logbooks undercounted the true number of bodies he helped bury. The victims, he said, included babies and young children.

“This system of undercounting is how the regime disappeared and buried so many more people than were recorded,” Naifa testified in 2024 in a US civil suit that was brought by a torture victim against the Assad government.

Ismandar’s name appeared 73 times among thousands of documents from 2018 and 2019 Reuters found and photographed during a visit to a military police forensics office that was abandoned in December as the forces of Ahmed al-Sharaa, now Syria’s president, swept to power in Damascus.

An inked stamp bearing Ismandar’s name appeared on documents from 2018 and 2019 that track how prisoners were taken first to Tishreen Military Hospital and then – after death – to the Harsta Military Hospital to be stored. The documents don’t mention mass graves.

From at least 2013 through 2018, however, 16 burial trenches were dug at Qutayfah with a total length of more than 1.2 kilometers, the Reuters analysis of satellite imagery and aerial drone photography found.

Local roads were closed when the trucks rumbled into the gravesite. In 2014, one of the trucks broke down on the highway and everyone in the convoy en route to Qutayfah stopped, according to the 3rd Division officer, who accompanied the group. Naifa gave a matching account of the incident.

The 3rd Division officer said he took a furious call from Ismandar’s commanding officer, Maj. Gen. Ammar Suleiman: “Orders from Mr. President: Block the international road until help comes.”

Suleiman was one of Syria’s top generals and part of Assad’s trusted inner circle. He led the military Medical Services and was Ismandar’s direct commander. His involvement was also confirmed in Naifa’s testimony and by a commander of the National Defense, a paramilitary that reported directly to Assad and was involved in Syria’s most sensitive security operations.

Suleiman did not respond to a message seeking comment.

Reuters didn’t find any documentation containing direct orders from Assad about mass graves in general or Operation Move Earth. But the Republican Guard officer and the National Defense commander said it was inconceivable that Assad hadn’t ordered it.

“I challenge you to find anything issued in Bashar al-Assad's name,” said the National Defense commander. “He knew that reckoning would come one day, and he wanted to keep his hands clean.”

Based on the pace of deliveries over those years, Haj Khalil, the former council chief, estimated Qutayfah held 60,000 to 80,000 dead by the end of 2018. That’s when the trench digging stopped, according to the Reuters satellite imagery analysis.

By then, with the help of Russia and Iran, Assad was widely seen as the victor in the civil war. Still, he had lost control of much of northern Syria to Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, or HTS, and to Kurdish forces, who each carved out autonomous regions.

One evening late in 2018, Assad summoned four military and intelligence chiefs to the presidential palace to discuss what to do about the mass graves, especially the Qutayfah site, said the Republican Guard officer. The officer worked in the palace at the time and said he was among a handful of people to see the meeting minutes.

The military intelligence chief, Kamal Hassan, came up with the idea of excavating the entire Qutayfah mass grave and moving the contents somewhere more remote, the officer said.

“The idea seemed crazy to most who heard it, but it received a green light from Assad,” he said. The main criterion for a new site was that it be under military control, he said.

Military intelligence chief Hassan ordered weekly reports to be sent to the presidential palace, the officer said.

Reuters could not reach Hassan, who is not believed to be in Syria, for comment.

In November 2018, work started on a concrete wall around Qutayfah, according to the officer, former council head Haj Khalil and a Reuters analysis of satellite imagery. A February 2019 satellite image shows the wall surrounding the entire mass grave. At 3 meters high, it blocked any view of the site from ground level.

More than an hour away in the Syrian desert, in early February 2019, the first of at least 34 trenches appeared. A new operation had begun on a windswept military base near the town of Dhumair protected by a series of berms and fences and ringed by mountains on all sides.

OPERATION MOVE EARTH

Written orders said the mission was to transport dirt and sand to a construction site, according to the Republican Guard officer and Haj Khalil. Clean-shaven with graying hair, Ismandar gathered the drivers a few minutes before they started work on their first day. He explained that it was actually bodies that needed moving because the mass grave location at Qutayfah had been exposed, said the military driver.

It was called Operation Move Earth, according to the Republican Guard officer and the National Defense officer.

“The instructions on the first day were: No one carries or uses phones. No one leaves the trucks during loading or offloading of the bodies, on pain of death,” said one of the military drivers. “No one would dare violate the orders.”

The truckers generally left Qutayfah around sundown and were forbidden to exit their cabs during loading, the driver said. He could see Ismandar in the rearview mirror, gesturing to him where to park. His truck rocked each time the bulldozer emptied itself, five or six times.

“Some were merely decomposed skulls and bones, while others were still fresh,” said the Republican Guard officer, who oversaw the work directly. “There were also many maggots. Hundreds, if not thousands, of maggots fell with each dumping from the bulldozer's bucket into the truck.”

Then, on Ismandar’s orders, the vehicles pulled into a tight line and headed toward Dhumair, six to eight dull orange Mercedes dump trucks trailing the colonel’s white van.

An overwhelming stench traveled with the convoy. Drivers and mechanics invariably began their descriptions of those late nights with the smell that filled the air, four days a week, from February 2019 until April 2021, excluding holidays, snow days and a Covid confinement that in Syria lasted about four months.

After years of these journeys, the trucks’ payload was an open secret for people living near both sites, according to a resident who still recalled the odor. “Everyone saw us,” said one of the drivers.

Without excavation, a close estimate of how many bodies are buried at Dhumair is impossible. But a convoy of six to eight trucks making four trips a week means a conservative estimate of about 2,600 trips including the time off. Based on that and the size of the trucks, it is reasonable to believe tens of thousands of people could be buried at Dhumair, experts told Reuters.

By the time Operation Move Earth was done, each one of Qutayfah’s 16 trenches documented by Reuters had been opened, satellite imagery showed. In all, Dhumair contains 2 kilometers of trenches, according to Reuters calculations. The drivers and one mechanic said each was about 2 meters wide and 3 meters deep.

Reuters reporters who visited the site this year saw human bones scattered on the surface, including what experts identified as a fragment of a human skull.

Ghazal, the mechanic, said he encountered the convoy frequently. The trucks dated to the mid-1980s and were prone to malfunctions.

Their periodic appearances at his garage gave him a chance to discern two types of bodies headed for Dhumair. Some were decomposed and covered in soil. Others appeared to be freshly dead, including young men and women. His two cousins, who also worked at the garage, also told Reuters they saw recently deceased bodies. Reuters could not determine where the newly dead bodies came from.

Ghazal led a Reuters team to the site, which he could identify from having been summoned there for an urgent repair on a truck that wouldn’t budge.

“Everywhere you look,” he said, pointing at the empty desert, “there are people buried beneath the earth.”

Ammar Al Selmo, a board member for the White Helmets organization that helps find and excavate mass graves, was the first to alert Reuters to a possible mass grave in Dhumair. He said Qutayfah locals had told the White Helmets the mass grave there was empty and a witness in Dhumair reported the convoys with bodies, but Al Selmo said the organization is short on staff and resources and didn’t verify either claim.

After learning of Reuters’ findings, he said the White Helmets plan an initial visit in coming days.

A Reuters analysis of hundreds of satellite images taken over years indicated a color shift in the disturbed earth at the Dhumair site. But even the most sophisticated commercial images lack the resolution needed for a close examination of the soil.

So Reuters set out to take thousands of drone photos with the intention of creating higher-resolution composite images of Qutayfah and Dhumair, using specialized photogrammetry software.

The composites showed that bulldozers repeatedly passed over the trenches to tamp down the soil. They also supported Reuters’ key finding that bodies had been transferred from Qutayfah to Dhumair.

The analysis of the drone images found color changes around the Dhumair burial trenches that suggest subsoil characteristic of that found at Qutayfah may have been mixed in with the soil at Dhumair. That’s what could be expected if the soil dug up with human remains at Qutayfah was then added to the soil at Dhumair, according to Dawson, a pioneer in forensic soil science at The James Hutton Institute in Aberdeen, Scotland, and Rocke, who specializes in finding burial sites using remote imagery.

Dhumair’s final trench was filled in during the first week of April 2021, according to the satellite imagery analysis. By the end of that year, Qutayfah’s rubble had been flattened, in an attempt to obliterate any signs of the now-empty mass grave. In imagery for both sites, the earth still carries the scars of attempts to cover up the burials.

The intelligence chief who had first come up with the idea of moving the bodies to Dhumair received one of the last weekly reports about the operation in late 2021 and turned to the Republican Guard officer. “Syria is victorious and opening up to the world again” were his words, the officer recalled. “We want guests to come and find the country clean.”

Ismandar, like Assad and many others in the government, fled Syria after the dictator fell, according to two former military officers familiar with his movements.

With Assad gone, Ghazal said the mass graves were the first thing he thought of as he watched footage of thousands of Syrians streaming into Sednaya Prison in vain hope of finding missing loved ones. Some of the burial sites were already known, including Qutayfah.

In December 2024, several local and international media outlets visited the newly accessible site, including Reuters. So did an association for missing Syrians, which noted that Qutayfah had been bulldozed sometime between 2018 and 2021.

No one reported that the trenches were empty.

Ghazal, who still lives and works in the area, said no one ever came to search the site in the Dhumair desert that haunts him still.

So many Syrians, he said, were looking in the wrong place.