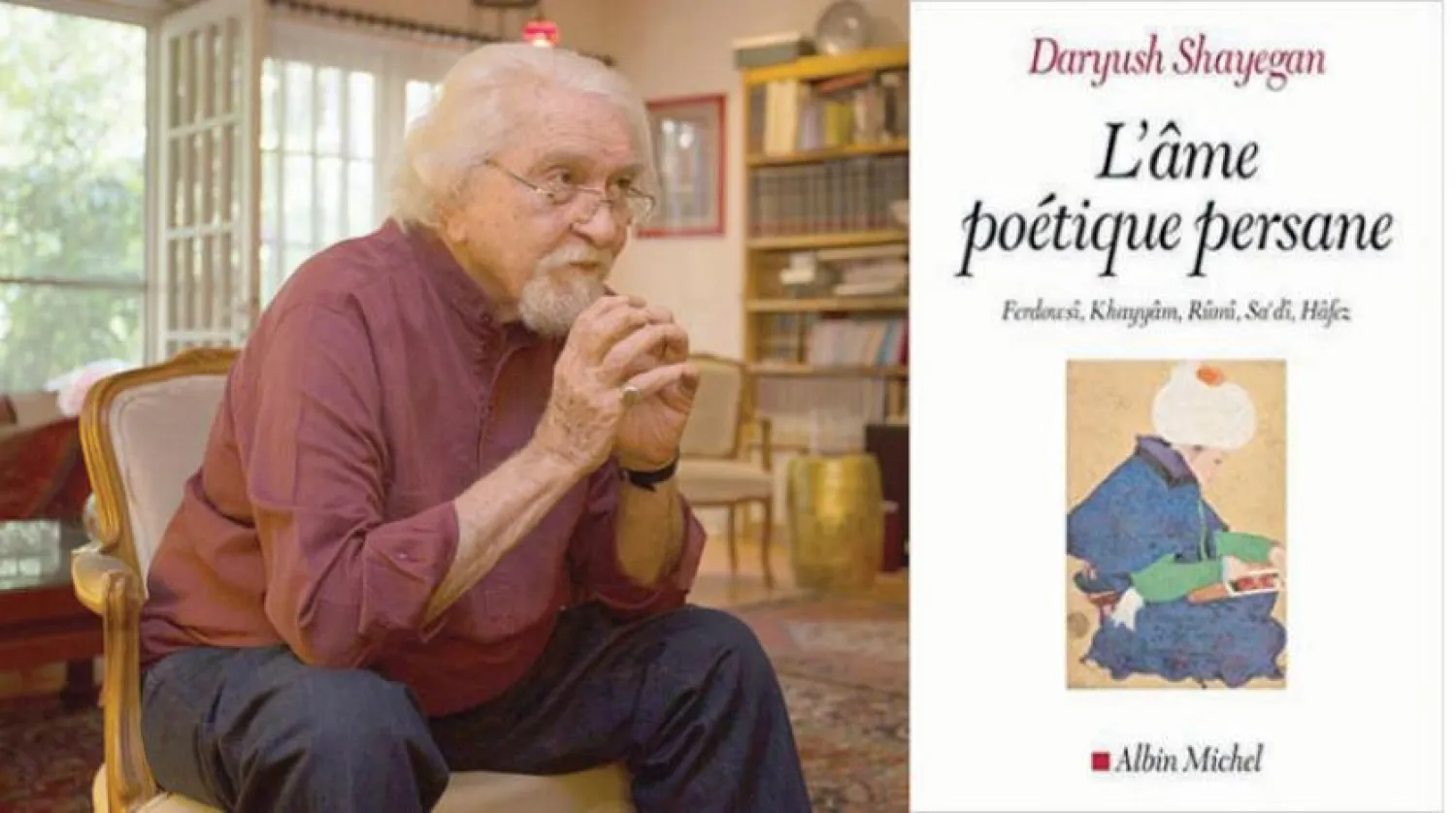

“We had one life, after all,” said the Daryush Shayegan as he sipped his double espresso as if it were the nectar of gods. “The question is: what did we do with it?”

The scene was a just over a year ago in a café in Paris’ posh Avenue Alma Marceau where we had gathered for lunch with a mutual friend, Professor Shahin Fatemi. At the time none of us knew that Daryush was on his last visit to the French capital which he had always regarded as a second home and that, a year later, he would pass away in his first home, his beloved Tehran.

Last Monday, a small group of mourners attended the burial ceremony in Tehran of the 83-year old Daryush under the watchful eyes of “Islamic Security” deployed to make sure there will be no “disturbances.”

The answer to Shayegan’s question, “what did we do with our life”, is both simple and complex in his case.

He has been described as polymath, philosopher, poet, mystic, linguist, and master in “Eastern” civilizations, whatever that means. But he had also dabbled in literary criticism, historic research, and, theological speculation. Moreover, he was also a keen collector and connoisseur of objects of art, books, and calligraphy.

Perhaps as a side-line, he had also dabbled in grand political strategy by promoting the concept of “a dialogue of civilization” which was first adopted by Empress Farah and, after the mullahs seized power in Tehran, Hojat al-Islam Muhammad Khatami who served as President of the Islamic Republic for eight years.

However, those who knew him best remember him for his passionate love of Iran, almost bordering on idolatry, and what he described as his lifelong love affair with the Persian language.

Shayegan was a typical product of what one may, at the risk of provocation, call the imperial culture of Iran.

He was born in Tabriz, capital of the East Azerbaijan province in northwestern Iran, of an Azeri father and a Georgian mother and thus learned both Azari and Georgian languages from childhood. At the same time, however, he learned Persian, the lingua franca, of “Iranzamin” (The Realm of Iran) which bound the many ethnic and linguistic communities of the country into a tightly-knit nation. At the time of Shayegan’s birth, Iran was home to 18 living languages, all but one of which represented ethnic communities. (Right now, sadly, only six of those languages still exist.)

The exception was Persian which, not identified with an ethnic group, was the language of every Iranian.

But Persian is a dangerous language; it could bewitch and bewilder you with its charm and mystery, throwing a lasso around your neck and leading you to regions beyond your intentions. It is like a femme fatale whose charisma makes you forget that she has a loaded gun hidden in her crocodile bag.

Shayegan was one of many Iranian intellectuals so smitten by Persian that, rather than commanding it in the service of their thoughts, became vehicles for the projection of its beauty. You marvel at a prose that, beautiful and fascinating, makes any thought it is supposed to express of secondary importance. “You say: I love it, it transports me to the seventh heaven, but what does it mean?”

Again, like many other Iranian intellectuals, Shayegan had to use other languages, in his case mostly French, to deal with the “beard-and-butter” of his philosophical speculations and historical observations. This is why most of his 18 books were written in French while he also used English for some seminar papers and essays.

Shayegan’s mastery of six languages, acquired during studies in England, Switzerland, France and, of course, Iran itself gave him direct access to the bulk of the literature he needed for inspiration and research in Islam, Sufism, Hinduism, Christianity and a whole raft of esoteric religions.

As a popular Professor of Comparative Philosophy at Tehran University between 1968 and 1979, Shayegan trained a whole new generation of scholars who have continued his work in all those domains. However, Shayegan’s focus during his decade of professorship was “Iranian Islam”, a term coined by Henry Corbin, the French Iranologist who forged a bond of friendship with Shayegan. He ended up translating part of Corbin’s work into Persian and writing a whole bio-critical book on the French master. Corbin and Shayegan shared a deep love of Iran and played a significant role in remembering and re-introducing some of Iran’s great half-forgotten Islamic philosophers.

In my view the Corbinist vision exaggerated Iran’s role in transforming Islam from a rather simple religious code into a complex culture and multifaceted civilisation. The French scholar failed to see that Iran and Islam were separate entities that met at some points but diverged at others. Worse still, Corbin was too focused on the mystic version of “Iranian Islam” to allow adequate space for the many other forms in which Iranians expressed their Islamic-ness.

In the end, trying to understand art or culture through the sole prism of religion may do a disservice to both. Does one need delving into Christian dogma to enjoy Bach’s “Passion According to Saint Matthew”? And should one attend a theological course to be admitted in the universe of great Persian poets such as Nasser Khosrow, Mowlawi, Hafez, and Nizami?

Or Saadi who said: ”Everything is good, in its own place!”

In the mid-70s Shayegan was spotted by Empress Farah, who was also French-educated, and invited to join the newly created Royal Philosophical Centre, coordinated by the Empress’s Private Secretary Sayed Hussein Nasr, a noted academic and scholar of Shi’ism.

A number of mullahs, some of whom later became prominent figures in the Khomeini’s Revolution, were also enlisted, among them Hojat al-Islam Mortaza Motahhari. Non-Iranian “philosophers” attracted to the scheme included the French Communist theoretician Henri Lefebvre, and Roger Garaudy, also a French Communist who had converted to Islam. Local philosophers who joined included Ahmad Fardid, a Heideggerian who was to achieve iconic status in the Khomeinist regime.

When Khomeini shut Iranian universities for two years to “purge and Islamicize” them, Shayegan found himself among thousands of professors and lecturers who were shown the door for not being Islamic enough.

Khomeini’s Cultural Revolution Committee, headed by one Jalal Eddin Farsi and including Abdul-Karim Sorush, a British educated Islamist philosopher, decided that those excluded from universities would have to undergo an Islamic re-education scheme to be considered for re-employment.

Many decided to go into exile rather than sign up for re-education. Some decided to stay in Iran but keep a low profile. Shayegan was among them.

The irony in all that was Shayegan had briefly supported the Islamic Revolution and even expressed the belief that Ayatollah Khomeini, the mullah who emerged as leader of the anti-Shah movement, might be “the Gandhi of Islam.” The philosopher’s saccharin-soaked vision of the Khomeinist revolution led many of his friends to stay away from him. (I was among them!)

But Shayegan was above such pettiness, especially because, as he was to admit later, his fascination with “the Gandhi of Islam” had lasted no more than a month. At the end of that month we happened to be together in a gathering and I feigned to ignore him. He, however, rushed towards me, tapped me on the shoulder and said: “I was mistaken. Let’s move on!” Who could resist that master demonstration of the power to subdue one’s ego?

Many years later, Shayegan put his “one month-long slip” into context by recalling that a good many Iranian intellectuals had been seduced by the idea of a revolution and that their fascination had done great damage to Iran.

“All our generation (of intellectuals) made a mess of things,” he wrote in a mea culpa that continues to have an echo among many Iranians.

Shayegan’s most directly political book ”What Is A Religious Revolution?” remains a masterpiece of socio-political observation of the confusion that reigns in many Muslim-majority countries trying to meet the challenges of the modern industrial, and now post-industrial, world in the creation of which they had played no role.

Shayegan further probed that theme in his “Mutilated Gaze” (1996) and “Cultural Schizophrenia: Islamic Societies Confronting the West” (1997), both of which helped inspire many debates across the Muslim world.

By the end of the 1990s, having observed the failure of the Islamic Revolution in Iran, Shayegan, always a man of passions, joined a 200-year-old dynasty of Iranian “westernizers” arguing that Iran won’t progress unless it adopted the values of the renaissance and its grandchild democracy. The result was his “The Light Comes from The West”, published in 2003 and then 2015.

The start of what was later called “The Arab Spring” in December 2010 gave Shayegan a new hope that Muslim societies might be able to find a way out of their predicament without breaking with their religion-dominated culture. It was in that hope that Shayegan dubbed the uprisings “The Islamic Awakening”.

Once again, however, Shayegan soon realised that dabbling in politics was always risky for a philosopher. By 2012, as “The Arab Spring” was beginning to turn into a dicey autumn and then a deep winter, Shayegan admitted to friends, including this writer, that he had been too hasty in supporting the uprisings.

But, where to go after that? Fortunately for Shayegan he could always return home, in the sense of seeking shelter in “Iranianism” which had always been a refuge for Iran’s disillusioned intellectuals for centuries. In that spirit, Shayegan used his prestige and moral power to launch a new series of books, many of them translations from various Western languages, on Iranian history and culture before Islam. The first series that I have seen are well chosen and edited, and printed at the highest standards. As often in Iran’s history popular disappointment in religion encourages a return to nationalism. However, excess in nationalism could be as deadly as excess in political religion.

We don’t know what this return to nationalism might lead Iran. But Shayegan had high hopes for it. The hope we could have is that he wouldn’t prove politically wrong once again.

The question what we did with our “one life” doesn’t apply to Shayegan. For he is destined to live for ever both as philosopher, and a great human being.