Not long after midnight on December 8, 2024, dozens of people gathered in the darkness outside the military section of the Damascus International Airport. Carrying whatever they could pack, they piled into a small Syrian Air jet.

Only an hour earlier, they were part of an elite cadre that formed the backbone of one of the world’s most brutal regimes. Now, in the wake of President Bashar al-Assad’s sudden fall and escape from the country, they were fugitives, scrambling with their families to flee.

Among the passengers was Qahtan Khalil, director of Syria’s air force intelligence, who was accused of being directly responsible for one of the bloodiest massacres of the country’s 13-year civil war.

He was joined by Ali Abbas and Ali Ayyoub, two former ministers of defense facing sanctions for human rights violations and atrocities carried out during the conflict.

There was also the military chief of staff, Abdul Karim Ibrahim, accused of facilitating torture and sexual violence against civilians.

The presence of these and other regime figures was recounted to The New York Times by a passenger and two other former officials with knowledge of the flight.

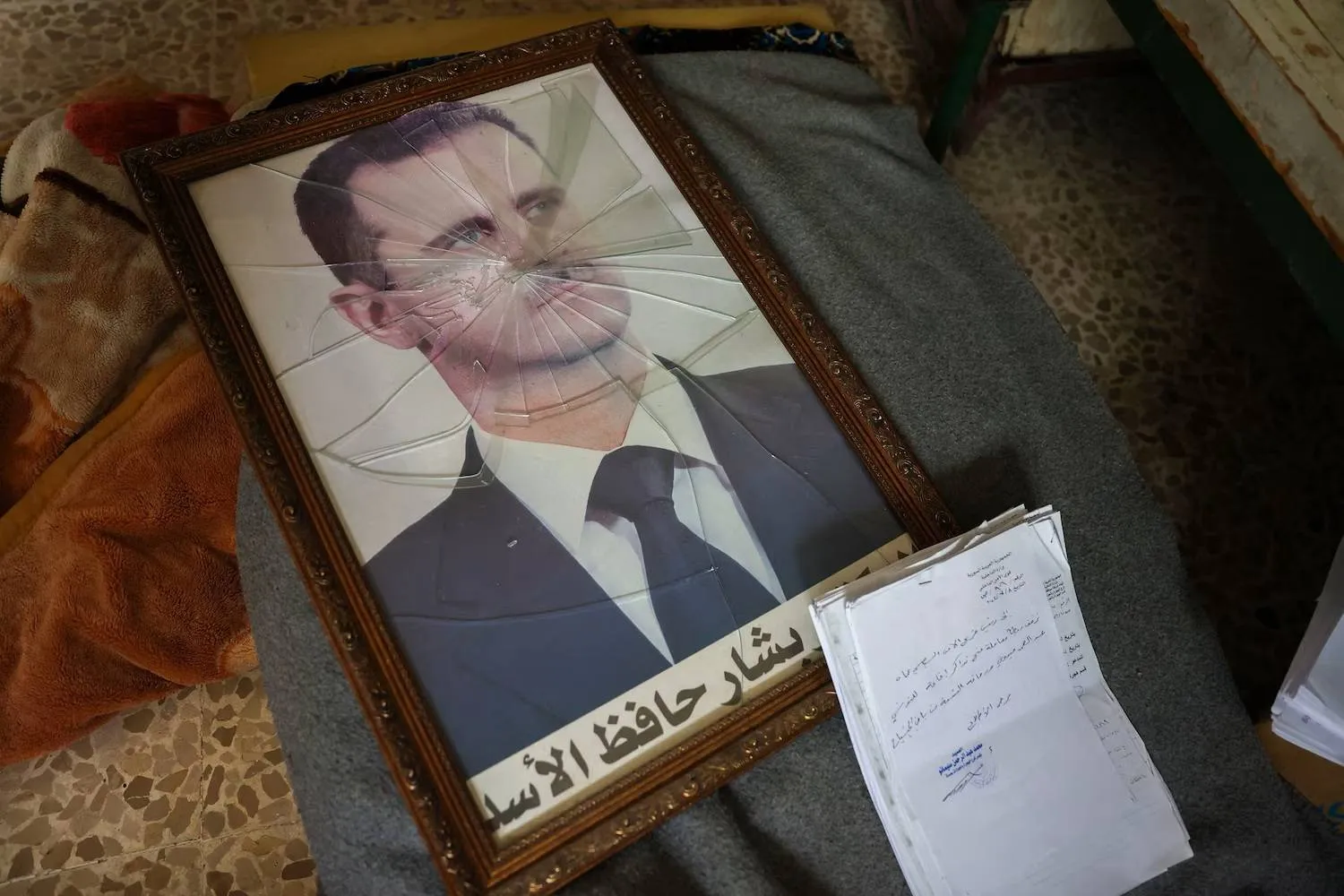

As a whirlwind opposition offensive encroached on the Syrian capital, Assad’s furtive flight out of Damascus earlier that night took his innermost circle by surprise and became the symbol of his regime’s stunning fall.

His henchmen quickly followed suit. In a matter of hours, the pillars of an entire system of repression had not simply collapsed. They had vanished.

Some caught flights. Others rushed to their coastal villas and roared away on luxury speed boats.

Some fled in convoys of expensive cars, as opposition fighters at freshly installed checkpoints unwittingly waved them on. A few hid out in the Russian Embassy, which assisted in their escapes to Moscow, Assad’s most important ally.

To the thousands of Syrians who lost loved ones, or were tortured, imprisoned or displaced by the Assad regime, their homeland had become a crime scene from which the top suspects disappeared en masse.

Ten months after the regime’s collapse, a nation shattered by war not only faces the immense challenge of rebuilding, but also the daunting task of scouring the globe to find and hold to account the people who committed some of the worst state-sponsored crimes of this century.

Former opposition fighters and Syria’s fledgling government are trying to locate them through informants, computer and phone hacks, or clues gathered from abandoned regime headquarters. Prosecutors in Europe and the United States are building or revisiting cases. And Syrian civil society groups and United Nations investigators are collecting evidence and witnesses, preparing for a future in which they hope justice can be served.

Their targets are some of the most elusive people in the world. Many of them wielded immense power for decades, yet remained public enigmas: Their real names, ages and, in some cases, even appearances were unknown.

The dearth of information has repeatedly led to inaccuracies in media reports, and on sanctions and law enforcement lists. It likely has helped some of the regime’s most notorious bad actors evade Syrian and European authorities since Assad’s fall.

The means to disappear

Over the past several months, a New York Times reporting team has been working to fill in the blanks about 55 of these regime officials’ roles and true identities, all former high-ranking government and military figures who appear on international sanctions lists and are linked to the deadliest chapters of Syria’s recent history.

The investigation has involved everything from tracing digital trails and family social media accounts, to scouring abandoned properties for old phone bills and credit card information.

Reporters interviewed dozens of former regime officials, many of whom spoke on condition of anonymity for their safety, as well as Syrian human rights lawyers, European law enforcement, civil society groups and members of the new Syrian government. They visited dozens of abandoned villas and businesses connected to regime figureheads and reconstructed some of their escape routes.

The current whereabouts of many of these 55 former key officials who enabled Assad’s dictatorship remain unknown, but among the dozen The Times has found, their fates vary widely.

Assad himself is in Russia and appears to have cut off contact with most of his formal circle, according to former Syrian officials, relatives and associates.

Maher al-Assad, who was second only to his brother Bashar in power over regime-era Syria, has been spending time living a life of exiled luxury in Moscow, along with some of his former senior commanders, like Jamal Younes, according to accounts by regime-era officials and business associates in contact with them, as well as video evidence verified by The Times.

Others, like Ghiath Dalla, a brigadier general whose forces were involved in violent repression of protests, are among several former officers plotting sabotage from Lebanon, according to ex-military commanders, who also shared text message exchanges with The Times. Dalla is coordinating with former regime leaders like Suhail al-Hassan and Kamal al-Hassan from Moscow, the same commanders said.

Some officials have struck murky deals to remain in Syria, according to an ex-military commander and people working with the new government. And one official, Amr al-Armanazi, who oversaw Assad’s chemical weapons program, was discovered by Times reporters to still be living in his own home in Damascus.

Keeping track of such a large group of figures poses a massive challenge for those seeking justice. There are criminal cases to build and the daunting task of finding a way to actually prosecute such cases.

But at the heart of this challenge lies the question of how best to coordinate global search efforts for people who don’t want to be found.

Many of them had easy access to government offices that enabled them to obtain genuine Syrian passports with fake names, according to former employees and regime figures. That, in turn, enabled them to obtain passports to Caribbean countries, they said.

“Some of these individuals have purchased new identities by acquiring citizenship through real estate investments or financial payments. They use these new names and nationalities to hide,” said Mazen Darwish, head of the Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression, a Paris-based group at the forefront of justice efforts on Syria.

“These people have the financial means to move freely, to buy new passports, to disappear.”

‘He’s gone.’

The mass exodus began late on the night of Dec. 7, 2024, after a moment of stark realization.

For hours, several of Assad’s top aides waiting near his office in the presidential palace had confidently fielded calls from their colleagues and relatives, several regime-era officials in contact with them that night said. The palace officials assured them the president was there, hashing out a plan with his military and Russian and Iranian advisers to confront the advancing opposition forces.

But that plan never materialized. And neither did Assad.

Realizing he was gone, the senior aides quickly tracked him to his home, according to three former palace officials. Shortly after, guards outside the president’s house informed them Russian officials had whisked Assad away in a convoy of three SUVs, along with his son and personal assistant.

According to the former palace aides, the only officials the president would summon to flee with him were two financial advisers. Assad would need their help, two regime insiders later explained, to access his assets in Russia.

The erstwhile president and his entourage got on a jet that flew them to Hmeimim, a coastal air base controlled by Russia, which had been his most critical backer in the war.

When they learned of the flight, the abandoned aides began frantically calling security officials and loved ones. The opposition fighters had reached the suburbs of Damascus and there was not a moment to lose.

“He’s gone,” was all that one senior aide said when he called a close relative, recounting that night to The Times. The aide ordered his family to pack their bags and go to the defense ministry in the capital’s central Umayyad Square.

There, the senior aide and his family joined several other security officers who had gathered with their families, and linked up with Khalil, the air force intelligence director. Khalil had arranged an escape flight, the one transporting many high-ranking officials, to Hmeimim. The plane, a Yak-40 private jet, left the Damascus airport around 1:30 a.m. on December 8, a passenger, who was one of the former palace officials, said.

Satellite-imagery analysis comports with this, showing that a Yak-40 was on the tarmac in Damascus in the days prior, vanishes on the night in question and seems to have reappeared at Hmeimim soon after.

The passengers who packed into the plane “were freaking out,” the former palace official recalled. The flight is only 30 minutes, he said, “but that night, it felt like we were flying forever.”

In another part of the city, Assad’s brother Maher, head of Syria’s feared 4th Division, was rushing to arrange his own escape. He called a family friend and one of his business cronies, according to two close associates. Maher al-Assad urged the men to leave their houses as quickly as possible and wait outside. Shortly after, he careened up the street in his car, then sped off with them to catch his own flight.

Swiping safes, dodging ambushes

Back in Damascus, some 3,000 members of the General Intelligence services were still inside the sprawling security compound in the capital’s southwest, unaware that regime elites had already fled. They nervously waited on high alert under their director, Hossam Louka — an official who oversaw mass detention and systemic torture.

One of Louka’s senior officers described him as someone extremely deferential to Assad. “He wouldn’t even move an ashtray from here to there without asking Bashar for permission,” he said.

The officer recalled that they had been ordered to ready themselves for a counterattack. The order never came.

A friend of Louka said he repeatedly called the intelligence director that night for updates and was always reassured that there was nothing to fear. Then, at 2 a.m., he said, Louka hurriedly answered the phone only to say he was packing to flee.

An hour later, Louka’s officers entered his office to discover he had abandoned them without uttering a word — and that, on his way out, Louka had ordered the intelligence service’s accountant to open the headquarters safe, according to one of Louka’s officers present at the time. Louka then took all the cash inside, an estimated $1,360,000. Three former regime officials say they believe Louka has since made it to Russia, though The Times has not yet verified their account.

In that same security compound, Kamal al-Hassan, another high-ranking former official, also raided his office headquarters. He took a hard drive as well as the money inside his administrative office’s safe, according to a friend and a senior regime-era figure in contact with one of al-Hassan’s deputies.

Al-Hassan, the head of military intelligence, is accused of overseeing mass arrests, torture and the execution of detainees.

His escape did not go as smoothly as the others. Al-Hassan was wounded in a gunfight with opposition fighters as he attempted to leave his home in a Damascus suburb formerly known as Qura al-Assad, or “Assad’s Villages,” an area where many regime elites lived in lavish villas.

He fled by hiding from house to house, the friend and regime-era official said, before eventually making his way to the Russian Embassy, which took him in.

The Times contacted al-Hassan through an interlocutor, who spoke to him by phone, but he would not divulge his location or agree to an interview. He did, however, recount his escape under fire, and said that he was sheltered at “a diplomatic mission,” before departing Syria.

Another official who sought refuge at the Russian Embassy was the retired national security director Ali Mamlouk, who helped orchestrate the system of mass arrest, torture and disappearance that was emblematic of five decades of Assad rule.

According to both a friend who said he had been in touch with him, and a relative, Mamlouk only learned of the regime collapse from a phone call around 4 a.m. As he attempted to join other officials fleeing to the airport, his convoy of cars was attacked by what the sources described as an ambush.

Though it was unclear who attacked him, they said he would have had many enemies.

As an intelligence director not only for Assad, but the dictator’s father and predecessor, Hafez, he knew the government’s secrets.

“He was the black box of the regime — not just since the days of Bashar, since the days of Hafez,” one of his friends said. “He knew everything.”

Mamlouk managed to get away unscathed and raced to the Russian Embassy, according to three people familiar with his escape.

Mamlouk and al-Hassan hunkered down there until Russian officials arranged a guarded convoy to get them to the Hmeimim base. Both men later reached Russia, the three people told The Times.

Close encounters

Several ex-regime figures said that, in an effort to minimize the regime’s resistance, there was a tacit understanding that opposition commanders would turn a blind eye to most Assad loyalists fleeing toward Syria’s Mediterranean coast, home of the Alawite minority sect to which Assad belonged, and where the Assad regime had recruited many of its security forces.

But it is unlikely such leniency would have been granted to the former Maj. Gen. Bassam Hassan. Few from Assad’s inner circle were more feared than Hassan, accused of a litany of crimes, including coordinating the regime’s chemical weapons attacks to the kidnapping of the American journalist Austin Tice.

Yet Hassan managed to escape undetected, despite sleeping through the first hectic hours of the regime’s fall. He was alerted sometime before 5 a.m., when one of his top commanders roused him from sleep, according to three people familiar with his story.

Hassan quickly arranged a convoy of three cars carrying his wife, adult children and bags stuffed with money, according to two of the people familiar with his story. He was so concerned about an attack that he had his wife and children ride in different cars, one associate said, to avoid the entire family being struck at once.

When their convoy approached the city of Homs, about 100 miles north of Damascus, fighters waved down the first car, an SUV, and forced Hassan’s wife and daughter out. They were ordered to leave everything, even their purses, inside the vehicle, according to a witness.

The fighters, apparently satisfied with their loot, paid no mind as the women got into the second car, joining one of the Assad regime’s most notorious henchmen.

The fighters had a scant chance of recognizing him. Bogus photos of Hassan have long circulated in the media. Even the United States and British governments do not use the right name or birth year for Hassan in their sanctions documents. The Times has obtained and verified perhaps the only recent photograph of Hassan.

Having cleared the checkpoint, Hassan eventually made his way to Lebanon and then Iran with the help of Iranian officials, according to interviews with officials from the Assad regime, Lebanon and the US.

He has since returned to Beirut as part of a deal to provide information to American intelligence officials. Associates said he had been spending his time at cafes and fancy restaurants with his wife. When reached on a Lebanese WhatsApp number, he declined to give an interview.

A bitter reality

For the tens of thousands of Syrians who were victims of the Assad regime, the pursuit of justice looks aimless.

It remains an open question whether the current government, under Ahmed al-Shara, has the capacity, or the will to aggressively pursue Assad officials accused of war crimes — that would, in turn, put some of his own officials’ alleged crimes under the spotlight, too.

And with foreign powers long divided over the war in Syria and the uprising against its former dictator, there is little hope for an international tribunal either.

For those fighting to ensure the regime’s crimes are not allowed to fade into history, a bitter reality remains: Assad’s top enforcers are still living large, and still one step ahead of their pursuers.

*Erika Solomon, Christiaan Triebert, Haley Willis, Ahmad Mhidi and Danny Makki for The New York Times