Lebanon has formally asked Syria to hand over information about a string of political assassinations that shook the country over the past four decades, many of which have long been linked to Syrian intelligence. The request was delivered during the second meeting of the Lebanese-Syrian Judicial Committee in Beirut on Wednesday, where both sides also discussed prisoners, missing persons, and refugee returns.

The most striking development, according to a senior Lebanese official who spoke to Asharq Al-Awsat, was Beirut’s call for Damascus to provide “all documents, information, and evidence” related to the killings of political, religious, military, and media figures during Syria’s decades of dominance in Lebanon. The Lebanese delegation also submitted a list of assassinated leaders whose cases remain unresolved.

During the period of Syrian tutelage over Lebanon, a series of high-profile figures were assassinated under circumstances that fueled suspicion of Syrian involvement. Victims included former presidents Bashir Gemayel and René Moawad; former prime minister Rafik Hariri; senior clerics such as Grand Mufti Sheikh Hassan Khaled and Sheikh Sobhi al-Saleh; as well as senior officers including Brigadier General François al-Hajj, the Lebanese Army’s head of operations, and Major General Wissam al-Hassan, chief of the Internal Security Forces’ Information Branch.

The Lebanese official explained: “We asked the new Syrian state under President Ahmad al-Sharaa to provide us with everything it possesses regarding these assassinations, from the killing of Druze leader Kamal Jumblatt to the assassination of researcher Lokman Slim. The Syrian side expressed readiness to cooperate.”

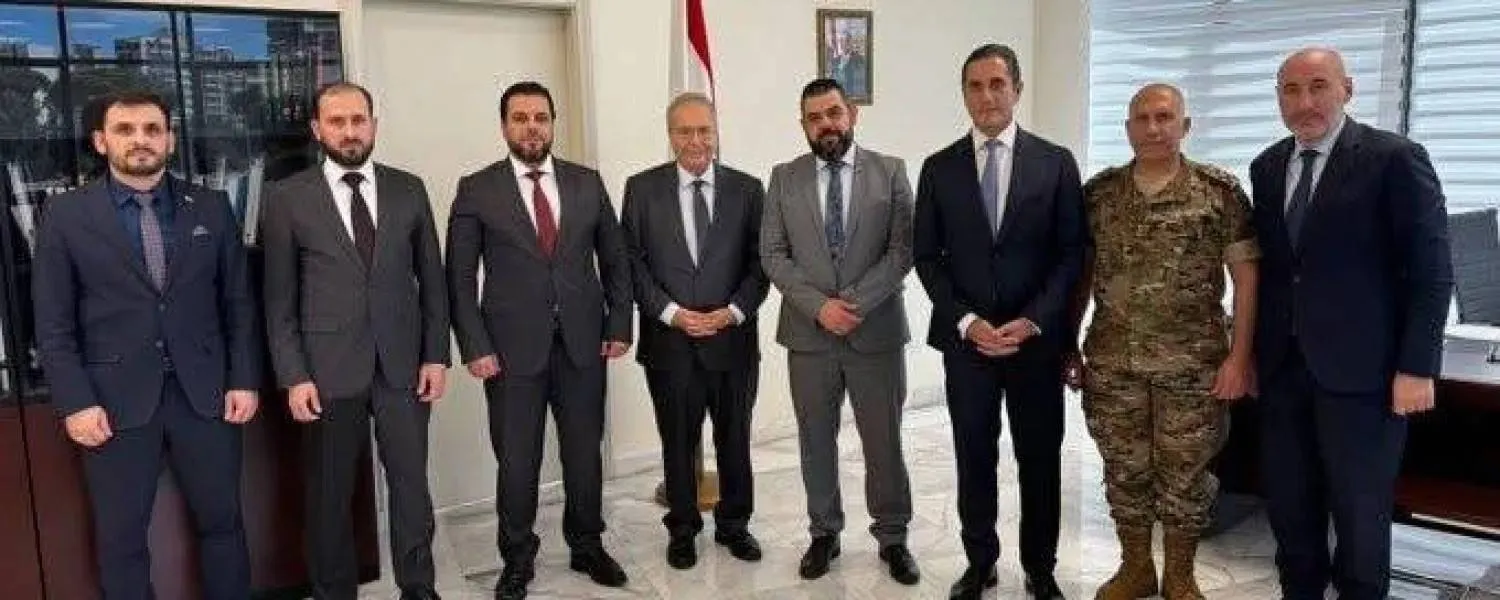

The joint judicial committee also advanced work on institutional cooperation. The office of Deputy Prime Minister Tarek Mitri announced that the two delegations had discussed a first draft of a bilateral judicial cooperation agreement and exchanged lists of Syrian detainees held in Lebanon. These included individuals arrested for ties to opposition groups against the former Assad regime but who had not committed crimes in Lebanon.

The statement underscored “the importance of quickly addressing a number of cases and expediting the judicial agreement, which would establish a legal framework for resolving the issue of Syrian prisoners and detainees in Lebanon.”

At the same time, the Lebanese National Commission for the Missing and Forcibly Disappeared met with its Syrian counterpart to exchange preliminary information. Both sides agreed to draft a memorandum of understanding on data-sharing between governments, commissions, and civil organizations, aimed at identifying missing persons still alive and clarifying the fate of others. The meeting, held at the Lebanese Ministry of Justice, marked what participants described as a turning point in bilateral ties.

For the first time, the two sides openly discussed sensitive issues that were restricted under the Assad regime. The Lebanese official emphasized that the dialogue was “built on transparency and mutual trust between Beirut and Damascus, with Syria’s new leadership showing readiness to cooperate on files that concern Lebanon. This could reset relations in a way that serves both countries’ interests.”

The fate of Lebanese missing in Syrian prisons remains the most difficult issue, fueled by contradictory reports since the Syrian army’s withdrawal from Lebanon in 2005. Damascus has consistently refused to release comprehensive data or provide accurate figures on detainees.

Lebanese negotiators raised the issue forcefully once again. Syrian officials requested a detailed list of all missing Lebanese, along with any information families or Lebanese authorities had on prisons where they were allegedly held, in order to trace records and clarify their fate.

At the same time, the issue of Syrian prisoners in Lebanon dominated much of the agenda. Both sides explored legal mechanisms to allow the repatriation of detainees and to review the bilateral judicial agreement.